June 2, 2019Showing 100 recent works by artists from 25 countries — including Bubble cabinet, 2017, by Dutch talents Jeroen and Joep Verhoeven (aka the Verhoeven Twins) — “New Glass Now” remains on view at Upstate New York’s Corning Museum of Glass through January 5, 2020 (photo by Prudence Cuming Associates, 2017, courtesy of Blain Southern). Top: Promise, 2017, by French-American artist Nadège Desgenétez, combines blown and sculpted glass (photo by Greg Piper).

The Corning Museum of Glass has organized not only one of the most visually arresting exhibitions of the year but one of the most surprising, too. “New Glass Now,” which runs at the Upstate New York institution through January 5, 2020, is unlike any previous show of studio glass. Yes, it contains bowls and vases and even the occasional drinking vessel, but it also displays a sculpture celebrating female empowerment, a rainbow-striped assertion of LGBT rights and a visualization of flooding caused by climate change. By including work that is informational, argumentative or politically controversial as well as beautiful or technically experimental, the museum has confirmed the importance of glass as a significant art category.

The exhibition is beautifully installed on white walls and platforms in the flowing galleries of the museum’s contemporary wing, a 2015 addition to the museum by architect Thomas Phifer that is the world’s largest space devoted to displaying contemporary glass.

It comprises 100 works, all made between 2015 and 2018 and coming from 25 countries. These include the United States, the United Kingdom and the usual glassmaking suspects, like the Nordic nations, the Czech Republic, Italy and the Netherlands, as well as more unexpected sources, such as China, Indonesia and Eswatini (formerly Swaziland). The artists range in age from 23 to 85. More than half are women, although Susie Silbert, Corning’s curator of modern and contemporary glass, who initiated the project and headed the selection committee, says the curatorial team “never even discussed gender in looking at the work.”

Every traditional glassmaking technique is represented — casting, blowing, molding, carving, etching, cutting, trailing and more — along with experiments combining glass with other materials. The pieces vary in size as well as manufacture: The smallest is a pristine paperweight-like cube by Miya Ando, laser etched and enclosing a subtle cloud-like form; the largest is Nate Ricciuto’s imposing mirrored and painted mixed-media staircase, meant to symbolize change and the creative process. A star of the show is the 2018 Rakow Commission, awarded since 1986 to support the development of new works of art in glass: Rui Sasaki’s installation comprises 200 hand-blown glass “raindrops,” each embedded with phosphorescent fragments that absorb simulated sunlight from fixtures in the space. Thanks to motion sensors, these lights turn off when a visitor enters the room, causing the glow of the piece to fade as one approaches, which reveals the outline of the drops.

Rui Sasaki, of Japan, presents the museum’s Rakow Commission. For Liquid Sunshine / I am a Pluviophile, 2018, she filled a room with blown-glass droplets embedded with phosphorescent elements that cause the pieces to glow. Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

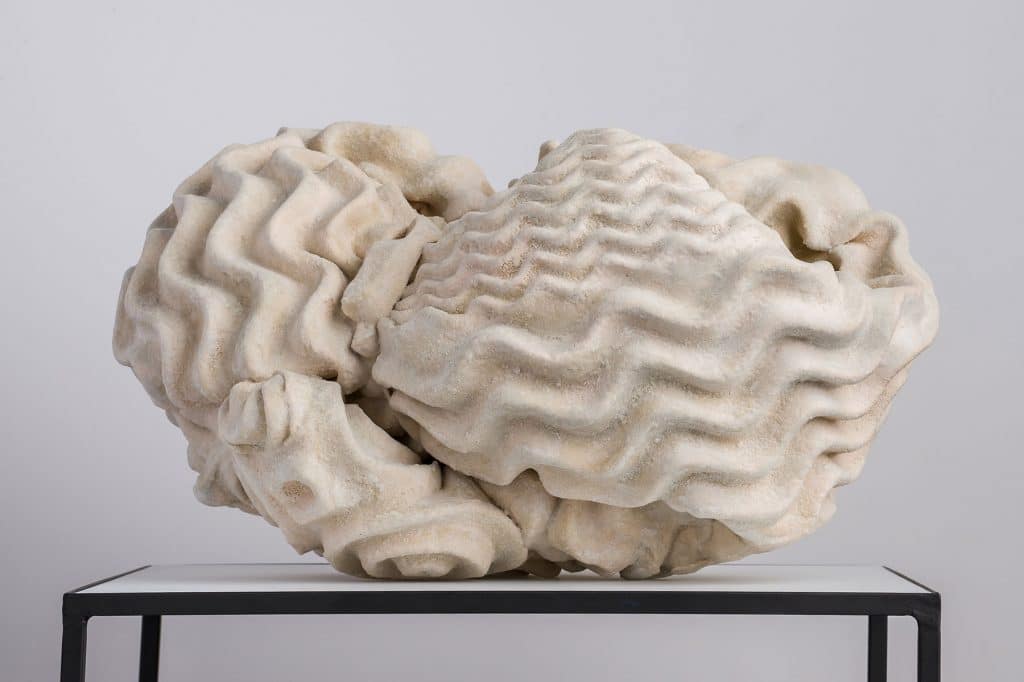

There are contributions from celebrated glass artists like Erwin Wurm and Toots Zynsky, whose signature glass “threads” are here arranged into a graceful coiled form that suggests a hank of yarn. Danny Lane’s interest in historicism is evidenced in a devitrified piece of cast glass that evokes ancient sculpture. Also making an appearance are prominent names not necessarily known for working in the material, such as Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec, the Verhoeven Twins and Tord Boontje, who collaborated with Swarovski on crystals with organic instead of faceted shapes to make lights that project ripples on the wall. Long-established producers like Iittalla, J. & L. Lobmeyr and Kosta Boda have a role, too; Martino Gamper’s tumblers for Lobmeyr are one of the show’s rare excursions into functionality — nine different cut, engraved, polished, painted or sandblasted variations on the familiar whiskey glass. Many of the contributors will be less familiar to the general public, although given the quality of the work, that seems likely to change. Among the standouts are Fredrik Nielsen’s assertive mixed-media piece composed of varied glass vessels set on pedestals and covered in glossy automotive paint and a Bahá’i temple in South America, shown in a photograph, whose exterior is formed entirely of borosilicate tiles by Jeff Goodman Studio. Also worth noting are Keeryong Choi’s elegant black glass jars inlaid with gold leaf and Ida Weith’s bound and bent glass tubes in a bundle with copper wire.

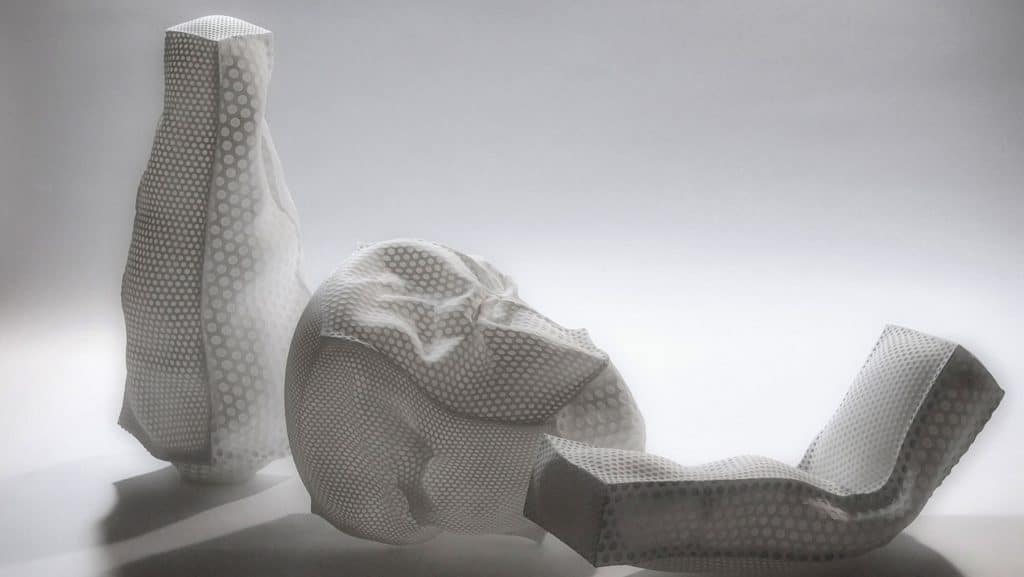

A number of pieces on display explore new ways of working with the medium. Matthew Szösz spun glass fiber into rope, then wove the rope into a basket shape that he fired in a kiln to finish. To create their envelope-pushing geometric sculpture, Stefano Bullo and Matteo Silverio screen-printed digital patterns onto hinged Venetian glass panels. And Karin Forslund created rock-like shapes by molding and then breaking glass of her own formulation. (Making glass from scratch is a painstaking process in which silica, lime and modifiers are combined with metal oxides for color and then melted; it hasn’t been common practice since the early days of the Studio Glass movement, in the mid-20th century.)

Alicia Eggert’s All the Light You See, 2017, mines the vernacular of neon roadside signs. Photo by Ryan Strand Greenberg

Organizing such a diverse exhibition wasn’t easy. Over a four-month period, the museum solicited work from a broad field of designers, glass artists and glass producers. “We did serious outreach. I wrote to everyone I could think of,” Silbert says. Her efforts paid off: 1,433 individuals and companies from 53 countries submitted a total of 3,754 digital images. A four-person committee — comprising Silbert; Aric Chen, curator at large for the M+ Museum, in Hong Kong; Susanne Jøker Johnsen, head of exhibitions at the Royal Danish Academy, in Copenhagen; and Wisconsin-based glass artist Beth Lipman — then narrowed the submissions down. Not all the winners were chosen unanimously; the exhibition label for each piece bears the initials of the jurors who selected it, providing insight into which objects were most, and least, agreed-upon.

Another neon piece, Megan Stelljes’s This Shit Is Bananas, 2017, uses the material in a decidedly different manner. Photo by Alec Miller

“New Glass Now” is the first international survey of its scale in 40 years. It follows precedents set by two previous exhibitions at the museum, in 1959 and 1979. “Glass 1959,” organized under founding director Thomas S. Buechner (who later became director of the Brooklyn Museum of Art), defined contemporary glass as a separate genre. It helped establish the field, which became known as the Studio Glass movement and ultimately made icons out of such artisans as Harvey Littleton and Dale Chihuly. It also opened up an entirely new category of collectible objects. The 1979 show, “New Glass: A Worldwide Survey,” was a broader examination that stimulated acquisitions by institutions and individuals and called attention to international developments in art glass.

The museum has revisited both shows in an informative corollary exhibition to “New Glass Now,” installed in Corning’s Rakow Research Library building, across from the contemporary gallery. There, archival photos and examples of works from the earlier exhibitions illustrate how the perception of art glass changed over the years: Almost 100 of the entries in the 1959 show were goblets; the greater variety of the work from 1979 reflects the influence of the studio craft movement.

Miya Ando‘s paperweight-sized Kumo (Cloud) for Glass House (Shizen), 2016, from her “Nature” series, is the smallest piece in the show. Photo courtesy of Miya Ando

With its expansive range and sophisticated curatorial interpretations, the current exhibition promises to be even more influential, to encourage serious study and to elevate the stature of a medium that can no longer be regarded as merely pretty to look at. “ ‘New Glass’ is about starting conversations, not drawing conclusions,” says Silbert. “I’m grateful for the opportunity to shift the narrative.”