March 12, 2023Whether it was rubies, silver teapots or forests in which to hunt, the Tudor kings and queens of Great Britain got first dibs on anything desirable. They decorated their bodies and their palaces magnificently, especially if the treasury was full and their grip on the throne was shaky.

The dazzling exhibition “The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England” provides us with evidence that all this splendor was used as a tool for building power, and then for advertising it and seeking even more.

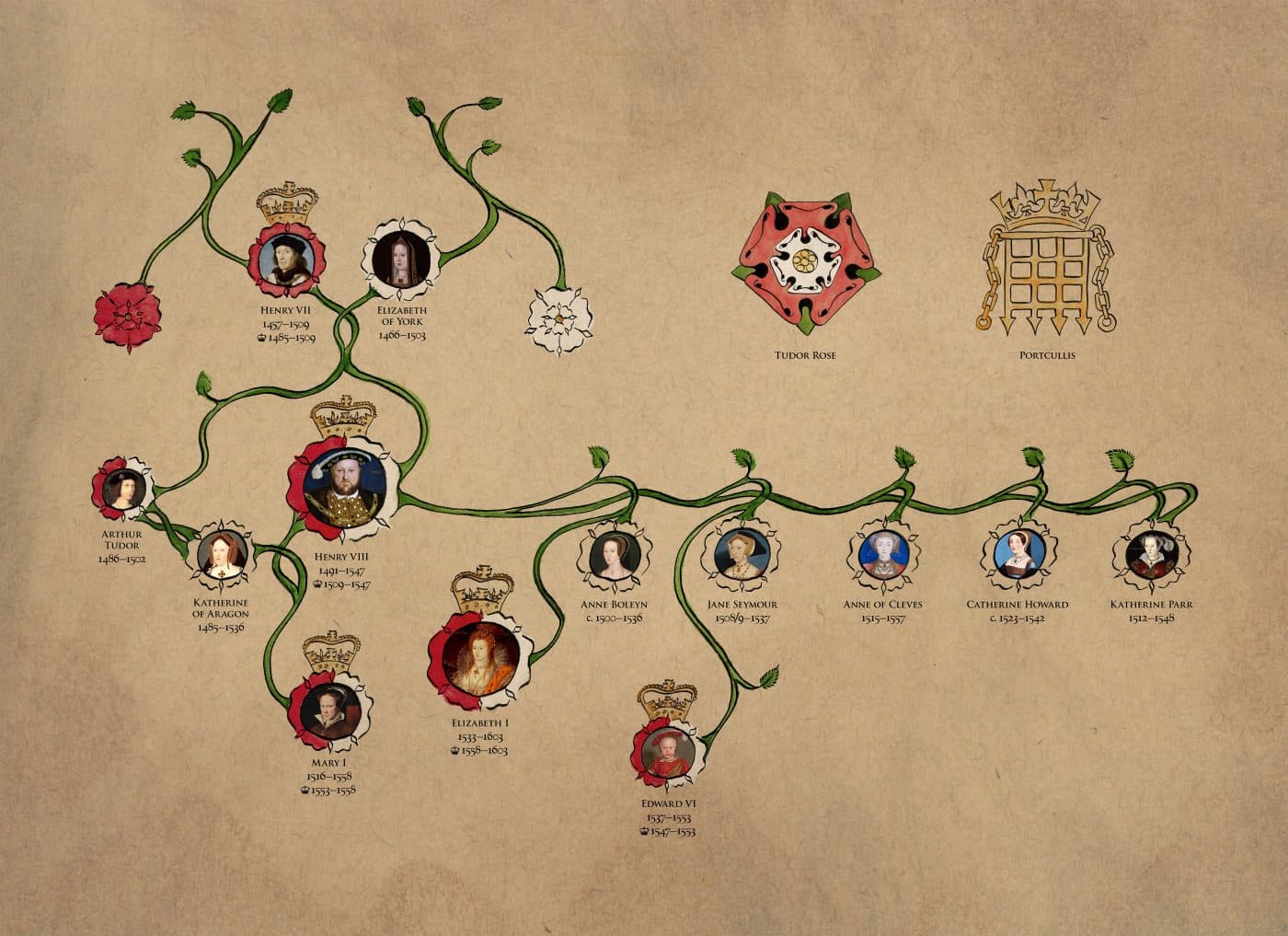

The Tudors ruled England from 1485 to 1603, but they had to fight to gain the right to rule and fight to keep it. Their choice of extravagant clothing, jewels, tableware, objects, gifts, paintings and other wall coverings was a way of proclaiming their legitimacy. Even today, the treasures they acquired cast a golden light on the dynasty.

Many of the Tudors’ most glittering pieces are featured in the blockbuster exhibition, currently at the Cleveland Museum of Art through May, after which it heads to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco for a late-June opening. (The show began its successful run at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art last year.)

The show is accompanied by an excellent catalogue. The text, informative and unusually well-written, reflects an awareness of the time we are living in without distorting the past. Indeed, it counterbalances the longstanding misogyny of recorded history with such a light touch one might not even notice.

to commemorate the 1588 defeat of the Spanish Armada. Right: This porcelain ewer, made around 1585 in China during the Ming dynasty, would have been incredibly rare, and therefore incredibly precious, in Elizabethan England.

The figure of Henry VIII, as painted by the workshop of Hans Holbein the Younger around 1537, with broad chest, feet wide apart and planted in the ground, staring us down, has long been the personification of Tudor greatness. Yet looking out at us from the cover of the catalogue of this exhibition is his youngest daughter, Elizabeth, after she became queen in 1558 A white lace ruff frames her face, and pearls delicately dance across her red hair. More pearls, long strands of them, hang from her neck. In this, the so-called Darnley Portrait — made around 1575 by an unknown Continental artist and on loan from London’s National Portrait Gallery — the queen is calm and thoughtful as she takes our measure.

Henry, of course, is not forgotten. Turn the catalogue over, and there he is, in a different Holbein portrait, fluffy white feathers on his hat, parallel rows of gem-set buttons on his embroidered tunic. But it’s the cover model who matters most. Without any ballyhoo, this catalogue gives pride of place to Elizabeth I.

The show does, of course, shine a spotlight on a great many other important figures, both female and male. You’ll find portraits of Mary Tudor, Henry VIII’s younger sister; and Edward, the son he so longed for, who ascended to the throne at 9 but died at 15. There are also pictures of Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn, and of dashing, flirtatious courtiers — men whose gaze and expression leave no doubt that they were seeking QEI’s favor, or perhaps more.

For all the abundance of beauty and art, this was an ere when rulers were a bloody lot. The Tudors make the Roys of HBO’s Succession seem like characters in a cozy, sleepy-time story for tots. And they used magnificent art as forms of propaganda, sometimes in a diabolically twisted way.

One of the most beautiful works in the show is a very large tapestry panel from a series of nine vignettes of the life of St. Paul, which Henry VIII had made around 1539. The subject of the panel is Paul’s burning of the heretics’ books. The fire takes center stage and whooshes up in a vast, cloud-like plume of glinting silver smoke.

Henry VIII commissioned this particular image to invite viewers — his subjects — to admire him as Catholics admired Paul: Paul had books burned in order to encourage pagans’ conversion to Catholicism; Henry set about destroying England’s monasteries and their contents to replace Catholicism, and the pope, with the new Church of England, led by the king himself.

Henry VIII succeeded in changing the religious order during his reign, but the fight to restore Catholicism in England went on after him. In 1588, with Elizabeth I newly on the throne, Spain sent an armada to conquer the country and reestablish the primacy of the pope there. When invasion and conquest seemed imminent, the monarch set off to Tilbury, the Spaniards’ likely landing place, where thousands of troops had massed to defend queen and country.

On August 9, Elizabeth stood before them and declaimed, “My loving people: I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a King, and of a King of England, too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which rather than any dishonor shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge and rewarder of your virtues in the field.”

The queen did not have to put on armor and raise a sword. Her navy, and bad weather, turned back the Armada. She became a heroine, and her country a force to be reckoned with. An engraved German map of 1598 that’s in the exhibition is drawn with the figure of Elizabeth I sprawled across Europe, dominating it. Her rule came to be known as England’s Golden Age.

Elizabeth I never married — proclaiming she was “already bound unto a husband which is the Kingdom of England” — and left no heir. And so, the Tudor dynasty ended with her death, in 1603. During her lifetime, power and greatness had been as important to her as they had been to her father. The continued rule of her family evidently was not.