June 4, 2023Raquel Willis’s voice leaves an unforgettable impression. The trans activist and writer galvanized crowds at 2017’s inaugural Women’s March, in Washington, D.C., and at the 2020 Brooklyn Liberation march for Black trans people. Her visibility as one of only two trans speakers at the Women’s March and as an organizer of the Brooklyn rally, which drew more than 15,000 attendees, has solidified her position at the forefront of today’s movement for trans justice.

Visibility has always been central to Willis’s journey. She endured pushback for her femininity from a young age and for coming out as queer in her teens. “But I found a resolve in [being visible],” she says. “Like, ‘Oh, there’s nothing wrong with me. The problem is that the folks around me can’t see expansively enough.’ ”

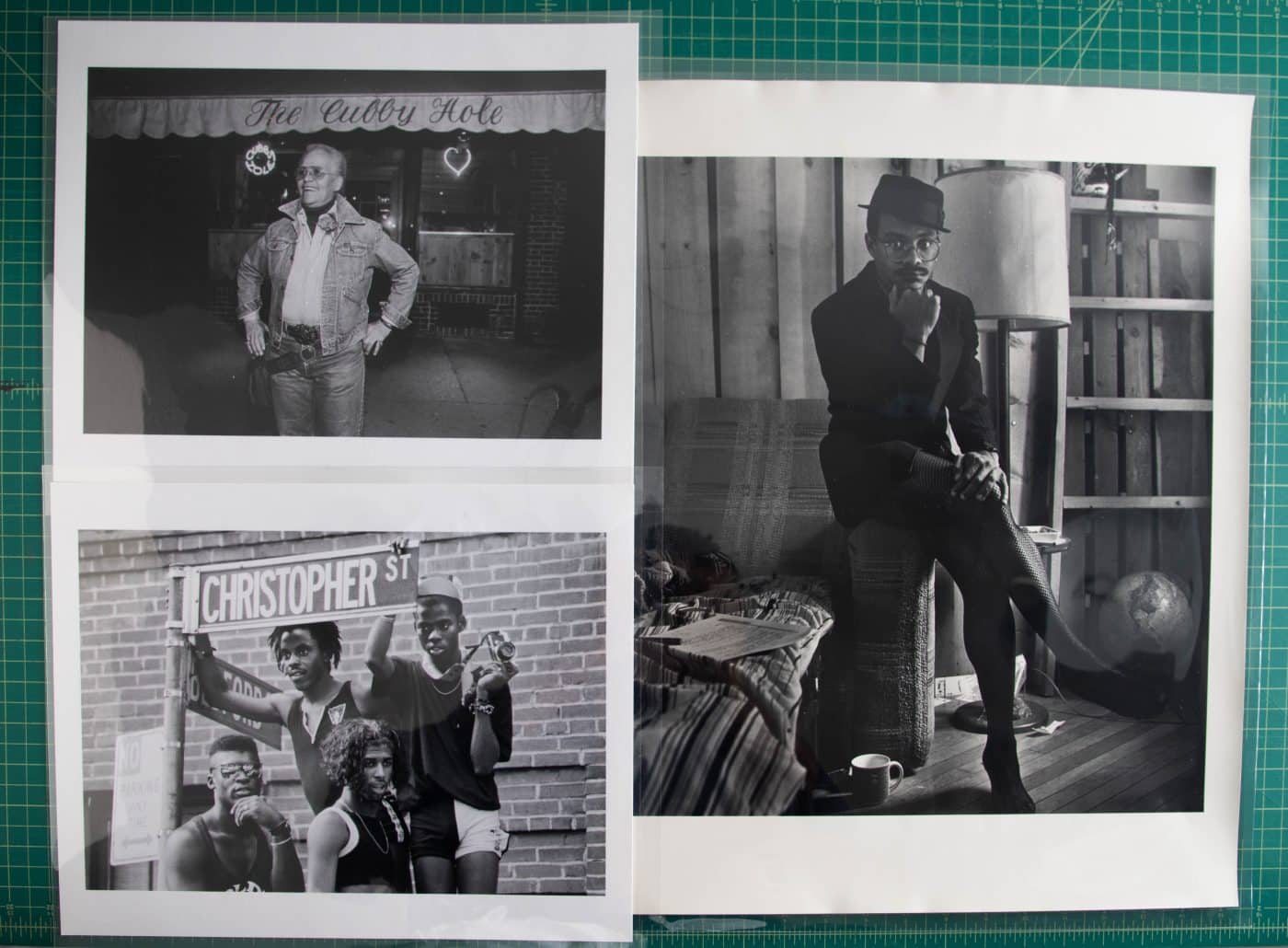

As part of her mission to expand everyone’s vision of queer and trans people, last fall Willis joined the board of New York City’s Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. Founded by Charles Leslie and Fritz Lohman, it’s the only museum in the world devoted to the exhibition and preservation of LGBTQIA+ art and history.

A gay couple, Leslie and Lohman held their first exhibition of works by gay artists in their Soho loft in 1969. They eventually opened a gallery nearby, and in 1990 they established the nonprofit Leslie-Lohman Gay Art Foundation. In 2006, the collection moved to its current space, on Wooster Street. Ten years later it was officially accredited as a museum.

However, there was still work to be done. Throughout much of its existence, the Leslie-Lohman had showcased cis gay artists. In an effort to be actively inclusive of the full LGBTQIA+ community, the board appointed five new members last year. Willis was one of them. “I was excited to be on the Leslie-Lohman board,” she says. “I’m always interested in how queer and trans people create, and particularly how we’ve created throughout time and how we’ve documented our voices and our narratives. Working with the Leslie-Lohman felt like a natural kind of inclination, because for me, queer and trans history continues to sustain me, to guide me, to give me a glimpse of what is possible.”

In many ways, Willis’s upbringing in Augusta, Georgia, is at the root of her activism. She notes that being from the South has made her more understanding and empathetic toward those who yearn for a different environment. “The struggle in the South is stauncher and thicker,” says Willis, who takes pride in having come into her own and having found her community in a place where LGBTQIA+ people are “expected to not exist at all.”

Her identity as a trans person, a Black person and a woman added another layer of complexity. While attending the University of Georgia, she mostly met white queer and trans people, which “didn’t meet the needs for me as a Black person,” she says. For her, finding community required multiple overlapping circles. As a result, her world includes a vast range of people and stories.

It was perhaps that quest to find stories like hers that laid the foundation for her career in journalism. In 2018, Willis made history as the first trans woman to be named executive editor of Out magazine, and during her time there, she won accolades for her Trans Obituaries Project. She has also served as director of communications for the Ms. Foundation for Women and is currently a media consultant for GLAAD, the world’s largest LGBTQIA+ media advocacy organization.

Willis’s vocal advocacy didn’t go unnoticed. Alyssa Nitchun, who joined the Leslie-Lohman in 2021 as its executive director, appointed Willis to the museum’s board the following year.

Nitchun’s vision for the institution is to reckon with its insular history of centering cis, white, male art. In partnership with the new board, she’s rethinking what kind of legacy the Leslie-Lohman wants to establish moving forward. “Art has the power to shift hearts, minds and culture to build justice,” says Nitchun. She wants the museum to be “a home for queer and trans artists who have not been represented before, have not been in the canon and have not had their voices and their stories heard.”

This year, the Leslie-Lohman and 1stDibs are partnering for the second time on a collection in celebration of Pride Month. The 2023 collection comprises furniture, art, jewelry and fashion offered by sellers from 1stDibs’ LGBTQIA+ community. In addition, Willis has curated a selection of her own favorites.

It’s no surprise that among the pieces she chose is Chad Kleitsch’s Untitled Flower # 70. “The phenomenon of blooming has defined so many crucial moments of my life,” Willis says. In fact, her forthcoming memoir is titled The Risk It Takes to Bloom. “It’s an ode to my dream of being as magnificent and as delicate as the magnolias in my childhood background,” she explains. “Here, Chad Kleitsch’s innovation in capturing florals lies in the use of scanography, reminding us that no matter how much technology transforms our lives, we will never be too far from nature.”

Another pick, REWA’s achalla ugo ⏐ Enchanted (Coca Cola) showcases the simple beauty of Black women. “Self-taught artist REWA isn’t afraid to exalt Black women in her art sans goddess accoutrement. There’s something beautiful about this glorious ambassador of Igbo culture honoring our sisters’ simply existing in the world as we are and as it is.”

In addition to being Pride Month, this June marks the 12th anniversary of the death of Willis’s father. Although their relationship was arduous as she struggled to fit his mold of Black masculinity, he was a profound influence in her life. Her choice of Aron Hill’s Cutout With White and Yellow is a tribute to him. “In the nineteen seventies, my late father was an avid painter,” she recounts. “He was simply a hobbyist and didn’t sell his work. He hung a few pieces in our house, but many of them were locked away in closets and a shed in our backyard for decades. He never returned to painting during the rest of his lifetime, but I was always taken by his approach to color and forms. The memories of my dad’s work blend in my mind with Aron Hill’s deft and refreshing approach to primary colors here.”

In straddling grief and jubilation during a month dedicated to pride, Willis has a realistic view of what comes next. “We will have loss in our lives, we will have moments of victory, and we will have moments of struggle.” But above all, she advises queer, trans and nonbinary people to never relinquish their joy. And if the road feels daunting, maybe it’s worth taking the advice that her father always gave her growing up.

“Walk like you know where you’re going.”