June 28, 2020During a 1977 television interview, the well-known fashion photographer Norman Parkinson was asked to tell his life story in three words. His response stunned his interviewer: “Not fashion photographer.” What then? Portrait photographer, Parkinson offered. “That’s why my fashion photographs do look a little different,” he explained. “Because the girls in them are people.”

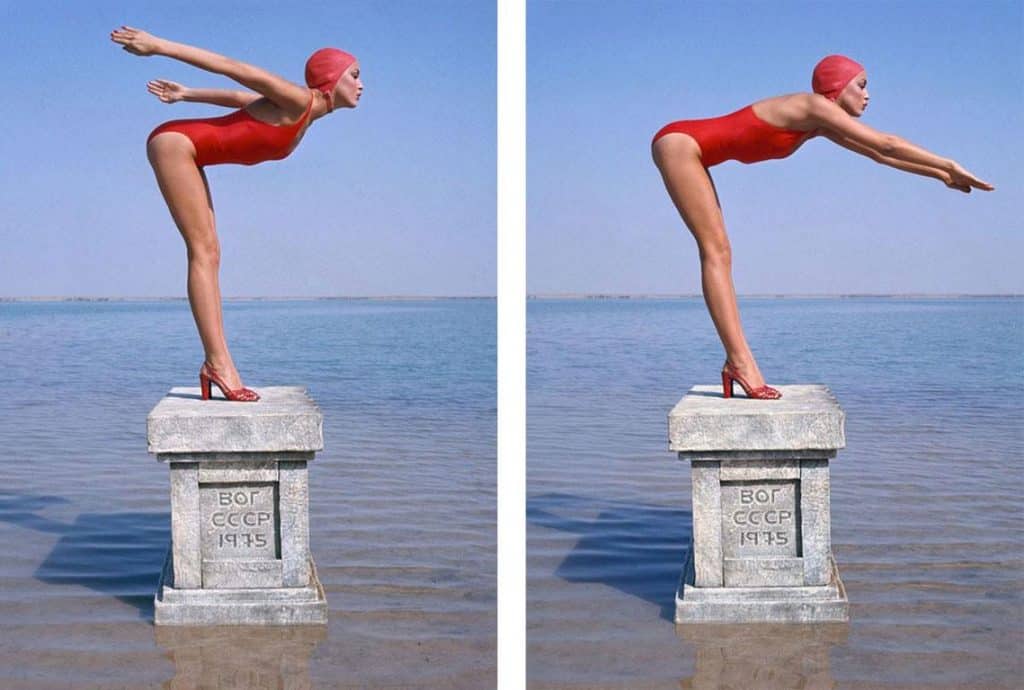

The idea of models with personality — smiling, laughing, riding on the back of an ostrich — was pure Parkinson, who died in 1990 at the age of 76. While other post–World War II fashion photographers immortalized flawless ice queens, Parkinson’s “girls” were quirky and adventurous —much like the six-foot-six photographer himself, who sported a sculpted mustache and had a penchant for fezzes along with a passion for travel. This bold, eccentric spirit is on full view in the exhibition “Norman Parkinson & Fashion Photography 1948–1968,” which was slated to open at Milan’s Fondazione Bisazza this spring but has been postponed until it is safe for the museum to resume operations.

“Fashion is like theater. Parkinson was constantly inventing new stories for this theater and transmitting these stories through his photography,” says the exhibition’s curator, Cristina Carrillo de Albornoz, who notes the lensman’s combination of exuberance and style. “He had all this joy and desire to convey the celebration of life, but at the same he has a unique sense of elegance, eccentricity and glamour.”

The exhibition depicts the sweeping social changes that occurred during the pivotal 20-year period it covers through Parkinson’s photography and accompanying works by such kindred spirits as Milton Greene, Terence Donovan, Terry O’Neill and Jerry Schatzberg. These images bear witness to an upheaval not only in fashion but also in the depiction of women. The exploration begins with Dior’s New Look, an ultra-feminine style launched in 1947.

Carrillo de Albornoz calls the late 1940s and ’50s a period of “radical femininity,” as they celebrated the traditional female hourglass silhouette along with conventional roles for women. Wartime images of independent Rosie the Riveter types were replaced by depictions of corseted women suited to serving cocktails and making babies. It was a look meant to please the eye, not to advance ease or self-expression. “In a way,” Carrillo de Albornoz says, “the motto of the time would be, ‘I am a woman, see my dress.’ ”

But the 1960s were just over the horizon, and the hegemony of decorum was about to crumble. The culture was being taken over by “revolutionary movements, social freedom and women’s liberation,” explains Carrillo de Albornoz, adding that in this environment, “those [1950s] feminine ideals didn’t work any longer.” The Swinging Sixties celebrated youth. Only youth. From London, where the youthquake began, came a fresh style embracing freedom, experimentation, big eyes and long legs. “We see Mary Quant. We see Twiggy with a miniskirt,” says Carrillo de Albornoz, who cites a new way of existing in the world epitomized by one development: “Women didn’t have to dress like their mothers anymore.”

Parkinson’s vision fit neatly with this more youthful, spontaneous style of femininity. Most photographers showed women “standing in scintillating salons with their knees bolted,” he told the New York Times in 1987. “I never knew any girls with bolted knees. I only knew girls that jumped and ran. So, I started to photograph these girls. Everyone said, ‘How bold!’ ”

And the “girls”? He had longstanding friendships with some legends of the industry, models who loved his gentlemanly yet unconventional ways. “He had a sensual mind and a sensual heart,” Carmen Dell’Orefice told a BBC interviewer. In her memoir, model and former Vogue creative director Grace Coddington describes her first photo shoot with Parkinson (her first photo shoot ever, in fact), which took place in the woods: “ ‘This is what I want!’ he shouted, mustache twitching as he leaped through the air from behind a tree.” Afterward, she recalls, they had tea. Of course, he was catnip for models in search of adventure. Jerry Hall, who began working with Parkinson in the mid-1970s, told the Financial Times, “I was so excited when I was working with him; I would go to bed thinking, what will I do tomorrow?”

She might have also asked, Where will we go? Parkinson liked to travel. He took models out of the studio to distant locations like Russia, the Caribbean and India. It was while reviewing his pictures of the latter that Diana Vreeland exclaimed, “How clever of you, Mr. Parkinson, also to know that pink is the navy blue of India.”

As air travel made the world more accessible, it widened fashion’s influence and expanded the range of dramatic settings. “There is a photo of two women in Trafalgar Square,” points out Carrillo de Albornoz. “They’re wearing Dior’s New Look, which is very French, but they are in London. Parkinson is saying, Fashion now is not only in Paris, it is everywhere.

“The way these masters documented fashion has been inherited by fashion photographers of today,” she continues. “Fashion is about theater. What these photographers are doing is representing the opposite of day-to-day life. This has not changed. People in the streets today don’t dress with as much elegance or glamour, but the way fashion is photographed is still the same — portraying the magic, making us believe that the world is beautiful.” And, she hopes, maybe even inspiring us to feel more beautiful ourselves, as Parkinson always did.