March 5, 2014Pat Steir, whose work is currently on view at Cheim & Read in New York, is photographed working on a painting in the 1990s (photo by Eric Boman). Top: Another view of Steir’s studio reveals a trio of her signature drip-style works (photo by Brian Buckley).

Ask Pat Steir about the meaning of her paintings, and she’ll tell you that it’s bound up in how she makes them — or how they make themselves, as she likes to say. For each one, Steir sets up initial parameters, choosing a palette and often dividing her 11-by-11-foot blank canvases into equal parts (halves, thirds, quarters or eighths) with snap lines of chalk or by eye. Then, in a process that can stretch weeks, months, sometimes years, she climbs her tall ladder and pours buckets of paint — powdered pigments she mixes with oil and turpentine in varying thicknesses — down the sections of the canvas in layer after layer. The weight of the pigments sliding downwards essentially paints the painting for her. The process is relatively simple, but the results are additive and build in complexity. The interaction of the different layers, the weave of the canvas and the temperature of the studio all collaborate to continually change the work before the artist’s eyes.

She likes how the record of the process becomes the image itself. “The way it works is always in part a surprise,” says Steir, who returns to her studio each morning to discover how gravity has subtly shifted the slowly drying pigments in a picture overnight. “It’s chance within limitations,” she says. “It’s embracing accident and chaos.”

Two Reds, 2013, sits in process in Steir’s studio; she lets the paint drip down the canvas over the course of weeks, months and sometimes even years. Photo by Brian Buckley

She does, of course, have a hand in the outcome. Steir controls the viscosity of the paint and the speed of its flow to some degree, with thinner washes streaking down the canvas in rain showers and thicker mixes moving in more slow motion. She may squirt water or pour straight turpentine on areas of the canvas to encourage certain melting effects, or flick arcs of paint from brushes across the diaphanous layers while poised on her ladder. (Professional tennis player Billie Jean King, who once did a studio visit, recognized the strength of Steir’s backhand.)

The artist has been a mainstay in the New York art world for more than 40 years, since receiving early acclaim in the 1970s for solo shows at Paley & Lowe and Xavier Fourcade. Steir, who was born in New Jersey and received her BFA from the Pratt Institute, in Brooklyn, in 1961, was part of the first wave of women artists, including Mary Heilmann and Jennifer Bartlett, to break through the male-dominated art world. This all happened in tandem with the rise of the women’s movement, but while Steir considered herself a feminist, she didn’t consider her art to be feminist. “I did this against all odds, and nobody was going to tell me what imagery was good for me,” says Steir, who was romantically linked to Sol LeWitt in the 1970s. She describes her early work as “intimate conceptual art,” in which she painted symbolic pictographs and made equivalencies between written words and images.

Steir received her greatest early recognition for The Brueghel Series (A Vanitas of Style), a monumental panel painting begun in 1978 and first shown at the Brooklyn Museum in 1984. (It toured ten other museums over the following three years.) To create the work, she divided the image of a 17th-century still life by Jan Brueghel the Elder into 64 panels, determined what artist each isolated section reminded her of — including Manet, van Gogh, Burchfield, de Kooning and O’Keeffe — and then painted the segment in that artist’s manner. As such, it became a history of the styles of modern painting.

A wall in Steir’s studio evinces her experiments with various paint colors and consistencies. Photo by Brian Buckley

Steir’s way of working changed in 1988 and was influenced by her longtime relationship with LeWitt, as well as her close friendship with the composer John Cage, who joined her on her honeymoon with her husband, Joost Elffers, in 1984. “They both had a system that operated itself,” she says, referring to LeWitt and Cage. “I’m a painter but I’m from the conceptual art generation. I was looking for something that would make itself generate more work.” Her early experiments with pouring layers of white paint produced her “Waterfall” series, the first of which hangs in the Metropolitan Museum. “I gave up trying to say anything. It was a real joy. I could just calm down.”

On a recent visit, the diminutive artist stood in her Chelsea studio, surrounded by her towering canvases, some of which were set to go on view in an exhibition at Cheim & Read, in New York, on view now through March 29.

Several of the works have dark, shadowy palettes. These canvases she initially divided into eight vertical bands, building the paintings up from undercoats of green and red, then veiling them with many layers of indigo and Payne’s Gray — Steir’s favorite color. “If you put it over light green it looks red,” she says of the dark gray paint. “Over other colors it looks blue.” On top of that, she threw washes of white, silver and gold, and then muted them again with scrims of the darker pigments. In making subtle contrasts between lighter bands and darker ones, Steir says she was interested in creating a sense of doorways or tunnels that viewers can mentally enter.

Steir admits that her artistic process remains “always in part a surprise.” Photo by William Steen

An experience several years ago of coming upon ancient Etruscan tunnels while driving through Tuscany with her husband inspired these works. Following a handwritten sign by the side of the road, they entered a passageway that was seemingly endless.

It was terrifying,” Steir remembers. “We thought we’d never get to the end.” Finally it opened up into a meadow. “It was a sacred tunnel,” she continues. “I’m still caught in that memory with these paintings. I’m sure Richard Serra has seen those tunnels.”

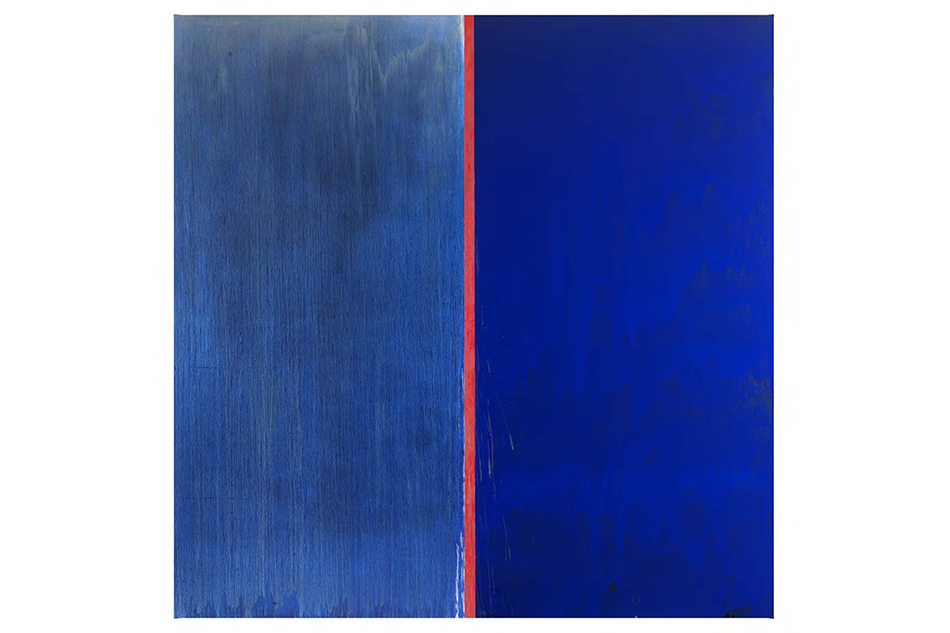

The more colorful paintings in the studio are divided down the middle into two vertical halves, and Steir thinks of these works as pages in a book or two sides of a similar story. “One contrasts and explains the other, like a visual balancing act,” says Steir. “I wanted them to be conversational.”

In one, green paint thrown over orange on the left half is held in dazzling tension with streaks of mica and brass, giving off a pinkish cast on the right. Steir hadn’t used mica before and didn’t know what to expect. “I sprayed water on it to pull it down, and the water made the mica tarnish,” she says. “It just did me a favor. I think it’s beautiful.”

Steir says she feels entirely suited to this physical and intuitive mode of working, which has monopolized her life for the last two and a half decades. “It’s painterly and conceptual at the same time,” says Steir. “I find the process so enchanting. It’s like magic.”