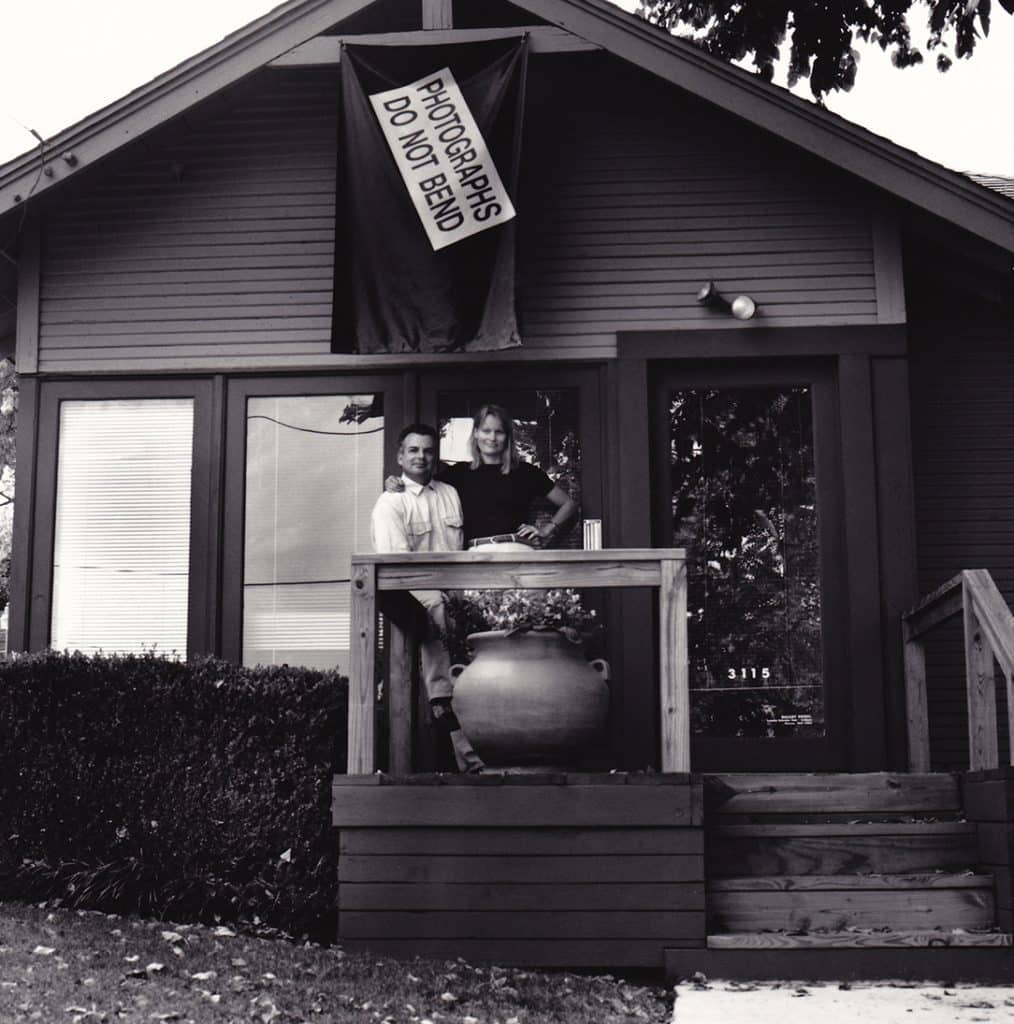

May 10, 2020When Burt and Missy Finger opened their photography gallery in a small A-frame house in Uptown Dallas 25 years ago, they brought indispensable experience to the enterprise. Not as dealers, but as collectors. The couple had spent a decade passionately acquiring photographs by the 20th century’s greats — Diane Arbus, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Robert Frank, André Kertész, Duane Michals and Jerry Uelsmann, to name a few — building on the knowledge that Burt had gained while working as a photojournalist and fine-art photographer in the 1970s. “We were wondering what we were going to do with all these photographs,” Missy says, “so we decided, ‘Let’s open an art gallery!’ ”

They named it PHOTOGRAPHS: DO NOT BEND Gallery, a reference to the stamp emblazoned on the many envelopes they’d received over the years, and they began nurturing a crop of collectors in Dallas just as the medium was gaining traction as a serious collectible. Now based in the city’s Design District, the gallery — today called simply PDNB — is an internationally recognized go-to source for historical and contemporary photography, representing a long list of esteemed photo-based artists and photographers’ estates.

As for the stellar collection the couple started with, Missy says, “Most of those treasures are in the hands of our clients or museums now.” Here, Introspective speaks with the gallerist about the ins and outs of collecting and selling fine-art photography.

Do you recall the specific encounter with photography when the medium first seduced you?

During my senior year in college, I became very passionate about art — mostly modernism, Abstract Expressionism. Later, when I met my husband and now partner in the gallery, he had a huge library on photography. He showed me the Aperture book on Diane Arbus, and I was blown away!

Arbus’s work really stuck with me — especially her eye for capturing images of people we cannot stare at. When we were financially able to start collecting photographs, Arbus’s Tattooed Man at a Carnival, Maryland, from 1970, was one of our first purchases. You can imagine how excited we were to have this photograph after poring over the Aperture book and learning more about her life and influences.

Then there were Robert Frank photographs from The Americans, his very famous and seminal document of his travels throughout his adopted country. And Duane Michals’s Grandpa Goes to Heaven was also a wonderful addition — a sequence of an old man dying and then going out the window. His idea of presenting a sequence of images to tell a story, along with his handwritten text, was very innovative. Collecting photographs can be addictive!

Texas has long been very fertile ground for photographers, and PDNB has introduced quite a few of them to a broader audience. Can you tell me about any in particular?

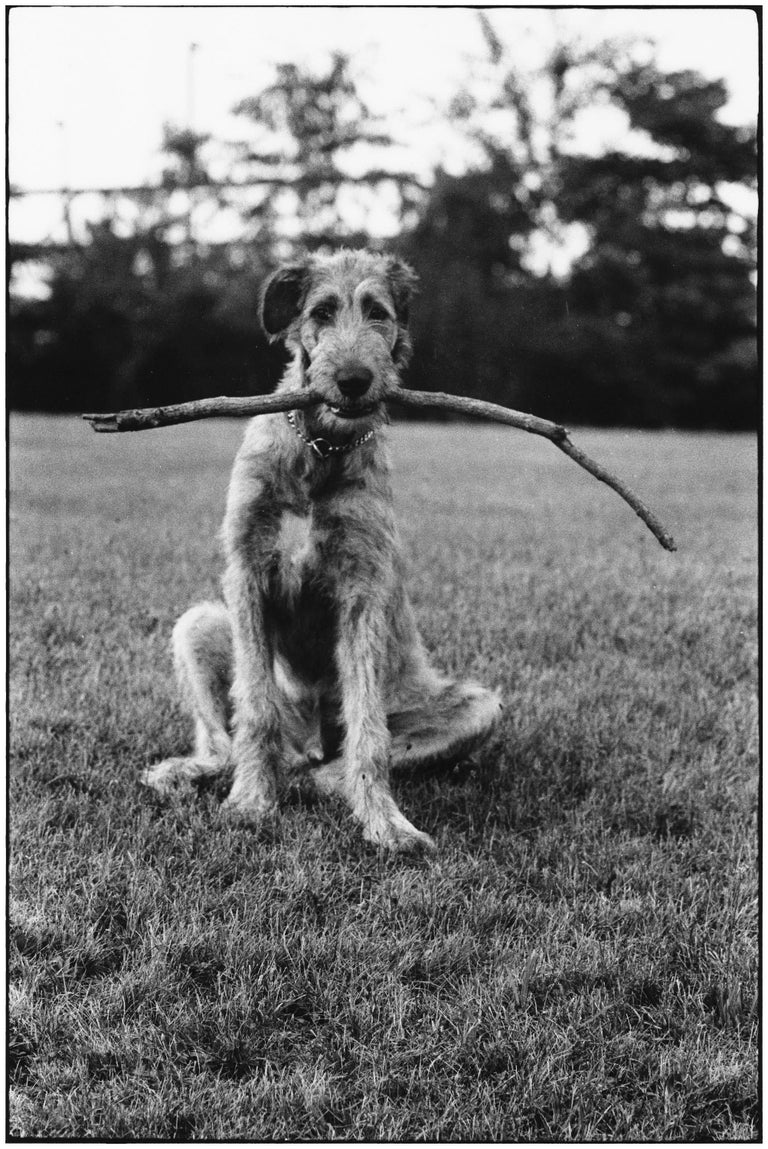

Keith Carter is a Texas legend. We were following his work before we opened the gallery, and our first show with him, in 1997, was a blockbuster. In the beginning, he explored the Southeast Texas culture around Beaumont. Keith’s highly acclaimed first book, From Uncertain to Blue (2011), documented small towns across Texas with odd names like Uncertain, Texas; Blue, Texas; Noonday, Texas; et cetera. He continues to be prolific in creating and experimenting with different print methods, from tintypes to photograms, and he has easily transitioned from the darkroom to digital, still creating beautiful photographic prints.

The terms original and unique are so important to connoisseurship, yet often misunderstood with multiples. Can you explain how those concepts pertain to photography?

What I tell beginners is that the print was made from the original negative. The negative is the original, and when the photographer makes a print of it, each is unique, even though each one might be part of an edition of, say, twenty-five. If you look closely at each print — and museums have done shows about this — you can see that each is indeed a unique object.

What determines the size of an edition?

Artists decide, but we do advise them. Peter Brown only prints in editions of twenty-five. Keith Carter started out printing in editions of fifty, but he didn’t print them all at once — he’d print on demand, as most every photographer printing editions will do. If there is an image that’s not as popular and he only sells five, he’s not going to keep printing more, so there may only be five prints of it. Other times, the whole edition would sell out, but it would be capped.

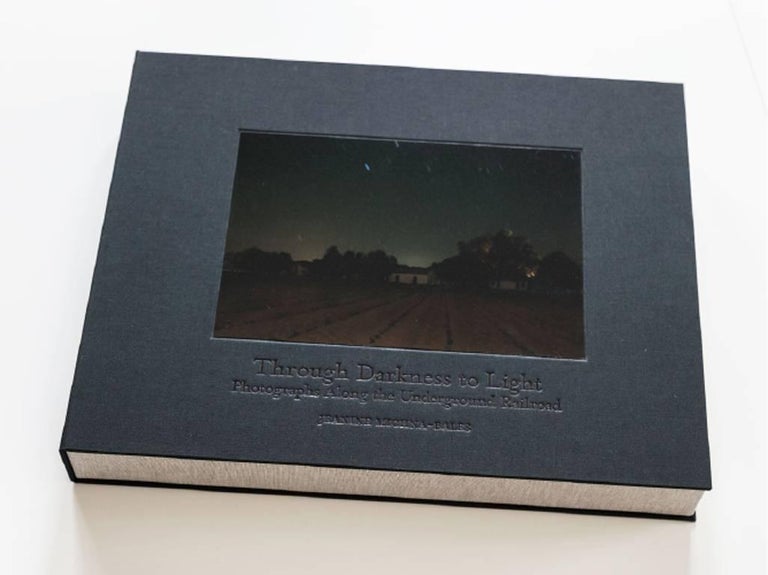

Photographers are thinking more about what museums are looking for, which is rarity, so they are doing smaller editions. But some artists want their work to get into people’s hands, they don’t want to limit it. Take, for example, Jeanine Michna-Bales. She’s an activist artist. She did an award-winning series of photos of forty sites along the Underground Railroad, and she wants the message to get out there, so she’s going to create larger-sized editions.

How can you be sure a vintage print is authentic and that, for instance, someone else hasn’t gotten a hold of the negative? Is it just a matter of experience and knowing what’s out there?

Every gallery that specializes in photography will probably represent several estates, and they’ll be experts in those estates and know the archive intimately.

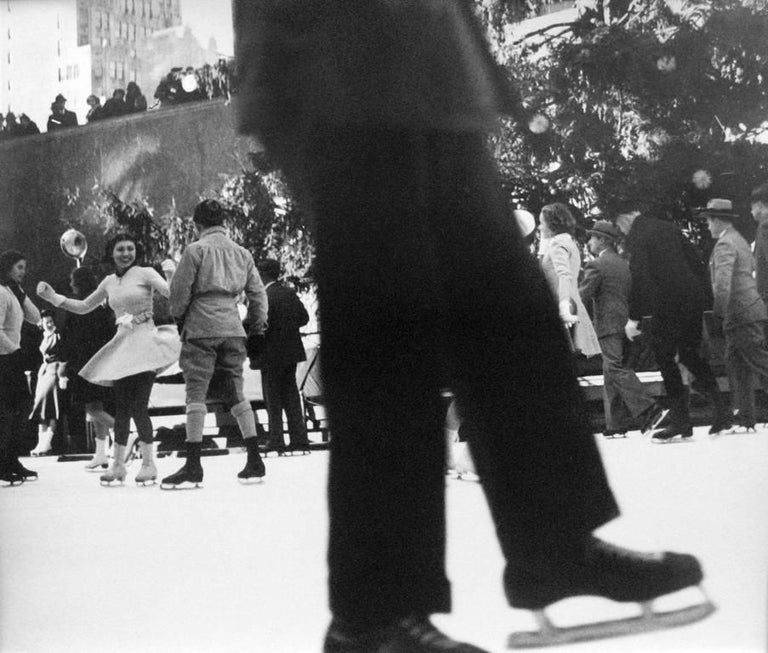

For instance, we represent the estate of John Albok. We have some exquisite vintage prints by him. Burt worked with John’s daughter for years and visited her often. They’d go through the archive and pull out prints. We know that archive very well now. And then there is the Association of International Photography Dealers, or AIPAD, which we belong to and which has been around for many years.

We photography dealers show at the AIPAD fair in New York together and have relationships, and we all pick each other’s brains if we have a question about something. It’s a network and community based on scholarship and years of being in this world, and that’s where you go to get knowledge about the medium.

Have there been any high points or discoveries in the past twenty-five years that stand out?

In 2000, we encountered the archive of the modernist photographer Ida Lansky, who was unknown at the time. She’d been living in Dallas when she passed away, in 1997, and her daughter contacted us. She was a nurse when she moved to Denton, Texas, in the 1950s, and then she studied art at Texas Woman’s University, where Carlotta Capron, an important Bauhaus-influenced photographer, taught.

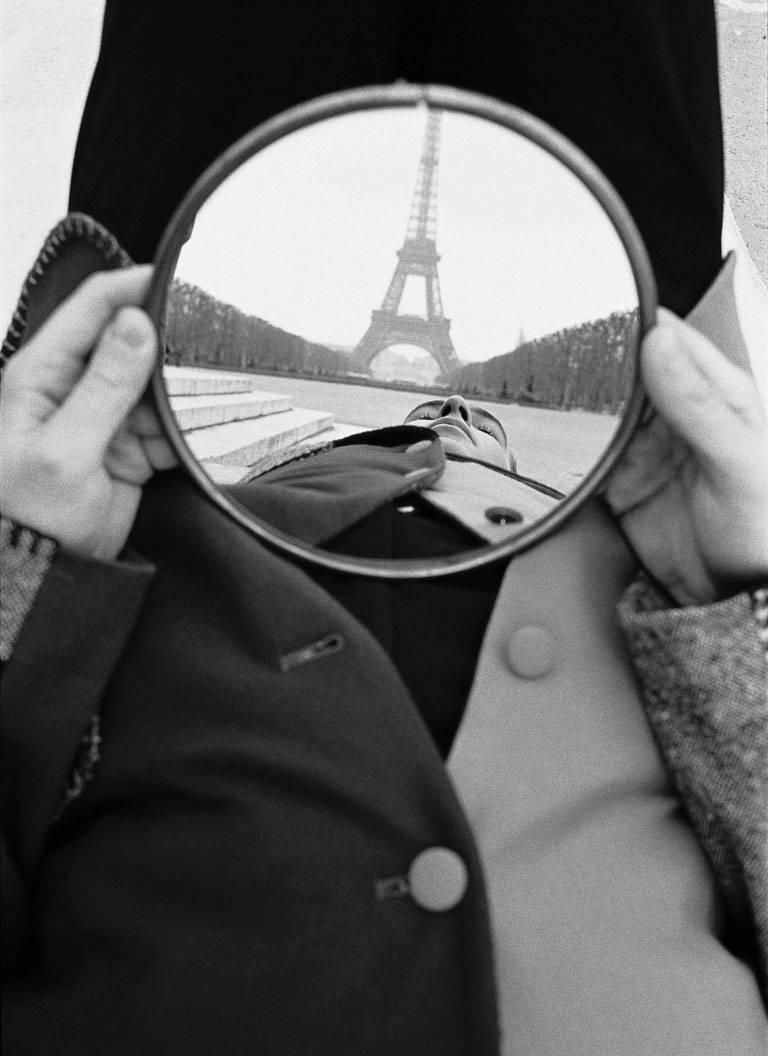

At the time, we were very interested in modernism. We were following the photography that came out of Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Paris and the New Bauhaus school, the Institute of Design, that was established in Chicago. The era was quite fertile for experimental photography, and this is why we were so excited to see Ida’s work in our own backyard.

Her photograms, using simple items around the house, were so brilliant. She had a good eye for design from the very beginning. Her knowledge of chemistry, from her previous career as a nurse, influenced her fascination with the medium. Although Ida’s career was short-lived, she did exhibit with other photographers, including Aaron Siskind and Harry Callahan. But then she put her art aside and studied library science. I think she wanted to divorce her husband and find a career that would pay, so she became a librarian.

We put her on the map. She’s in museum collections now, including that of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. In 2021 and 2022, her work will be included in a comprehensive exhibition, “Women in Abstraction,” at the Pompidou Museum in Paris and the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain.

Are there any photographs that would make you weak in the knees to see in person?

Burt loves the Brancusi photos of his sculpture studio, which you see every now and then. They’re very prized photos, and if we ever had one we’d have to sell it. He also loves Gustave Le Gray’s seascapes. We started as big fans of modernism, László Maholy-Nagy’s work and Man Ray’s rayographs were at the top of our list. When I saw Maholy-Nagy’s show at the Guggenheim a few years ago, I was just astounded. It’s so hard to imagine that he made those experimental images so long ago. The whole show was overwhelming. That’s the beauty of art — you lose yourself in it.

Talking Points

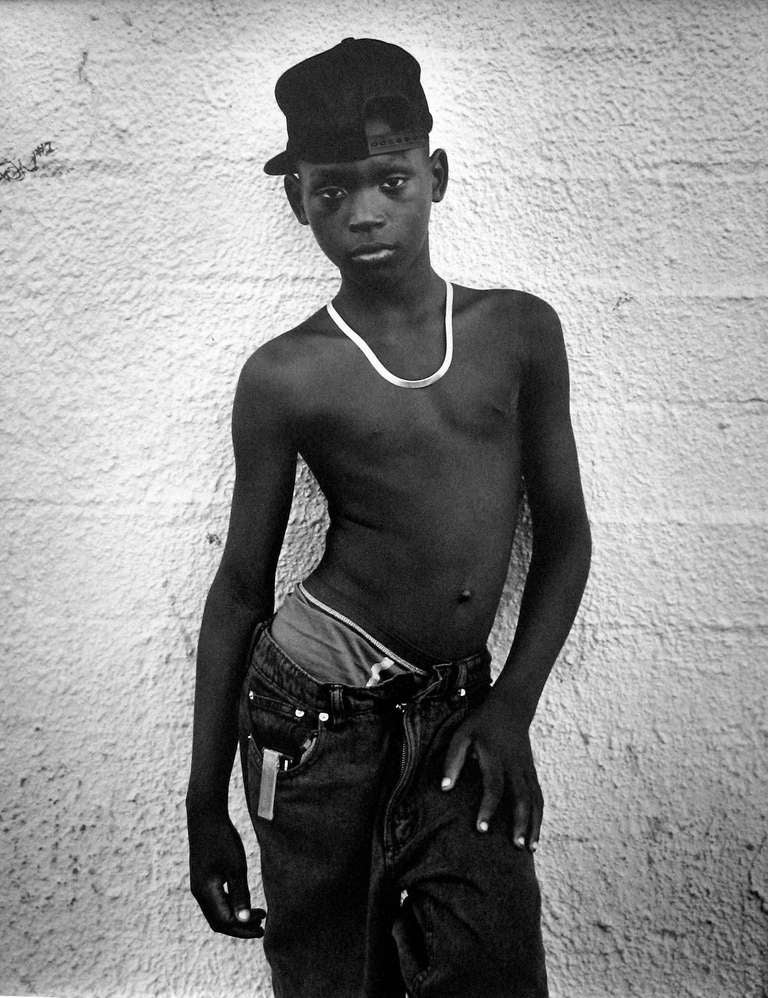

Missy Finger shares her thoughts on a few choice pieces