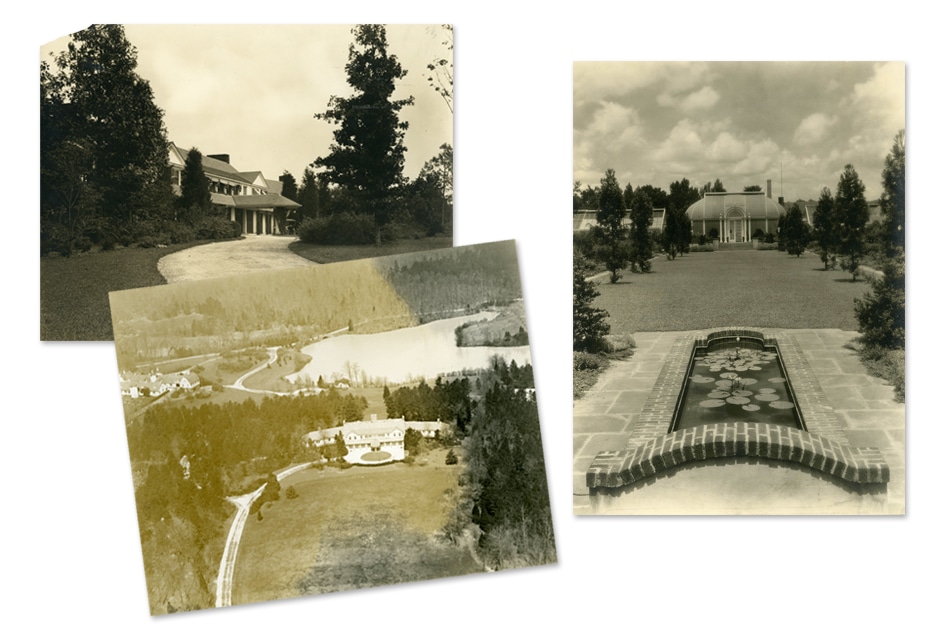

July 10, 2017The stately Beaux Arts gardens and conservatory at Reynolda House beckon visitors to the events and special exhibitions commemorating its centennial (photo by Ken Bennett). Top: The front facade of the 64-room 1917 house is softly lit during twilight. All photos courtesy of Reynolda House Museum of American Art, unless otherwise noted

Quick: What’s the Frick of the South? That’s how the late, great critic Robert Hughes — not an easy man to please — referred to Reynolda House Museum of American Art, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, comparing it to New York City’s storied collection of art and furniture amassed by Henry Clay Frick.

Given that it holds more than 250 artworks, many of them masterpieces by the likes of Arthur Dove, Grant Wood, Charles Burchfield, Jacob Lawrence and Thomas Cole, you’d think that everyone would know about Reynolda, but so far it’s flown a bit under the radar, by design. Genteel Southern discretion and all.

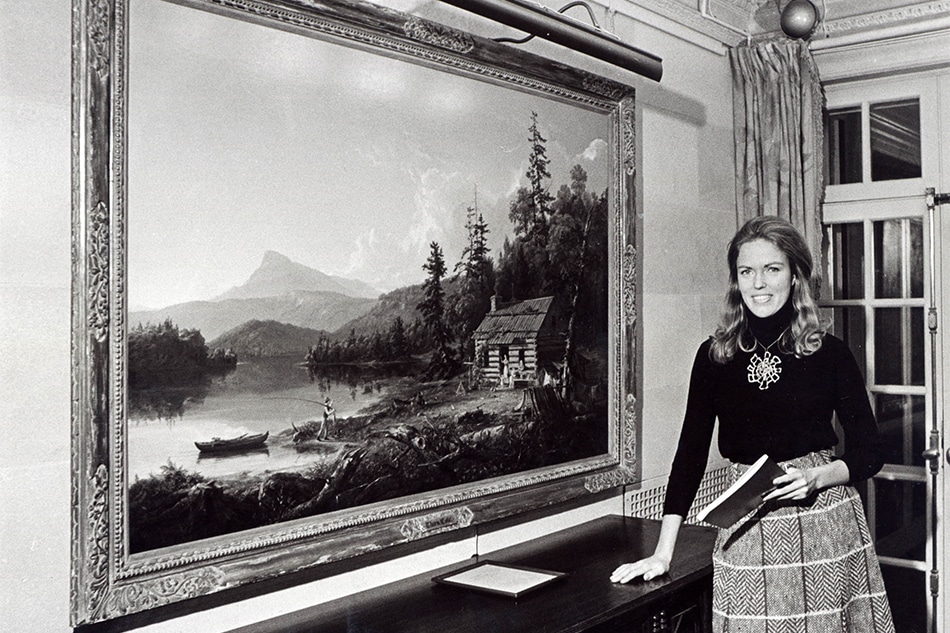

No more: Barbara Babcock Millhouse, the founding director of the museum and the granddaughter of tobacco titan R.J. Reynolds, is turning up the dial on Reynolda’s public profile.

“We made a decision at some point to be regional, but we feel we’re not known, and we should be,” says Millhouse, 82, who lives in New York but travels back to North Carolina regularly. Special occasions can help with visibility. This year marks the 100th anniversary of the completion of Reynolda House and the 50th of the museum’s founding, commemorated with attention-getting exhibitions and events. There’s also a forthcoming coffee-table book, Reynolda: Her Muses, Her Stories, published by the museum.

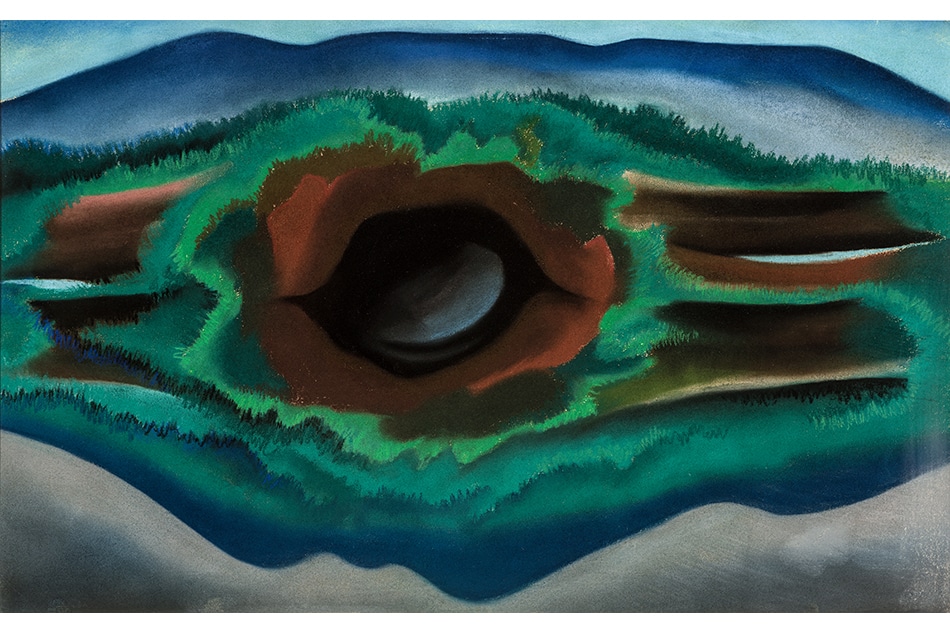

Among the planned shows is “Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern,” which has done boffo business at the Brooklyn Museum and will be on view at Reynolda from August 18 through November 19. Next year, an exhibition focused on Frederic Edwin Church will take its place.

Giant Magnolias, 1904, by Childe Hassam was one of the original nine American paintings Millhouse purchased in 1966 with her newly established Art Acquisitions Fund.

The selection of those artists is no coincidence, since they are among the many great names in Reynolda’s collection. A number of works are charmingly installed around the grand old 1917 house that Millhouse’s grandparents built, which has ample space, given its 64 rooms; a newer wing for special exhibitions and events was added in 2005.

Millhouse came to her role as museum founder in an offhanded, familial way after the house was already open to the public and set up as a foundation by her parents, Charles H. Babcock and Mary Reynolds Babcock. Each month, artworks were borrowed from major institutions and displayed for Junior League tours and the like.

“I’ll tell you how I got to be president instead of my siblings,” she says. “There was a sofa in R.J. Reynolds’s study that they reupholstered — in vinyl. I had spent three years at Parsons School of Design. I said, ‘They are going to ruin everything.’ My father said, ‘Well Barbara, why don’t you serve as president of the board?’ ”

Millhouse adds, with a soft chuckle, “I learned that you never complain.”

But the young Millhouse didn’t just coast with a cushy family assignment. She raised $300,000 from foundations to create an acquisition fund. “I wrote letters,” she says. “It wasn’t the kind of applications you have to do today.”

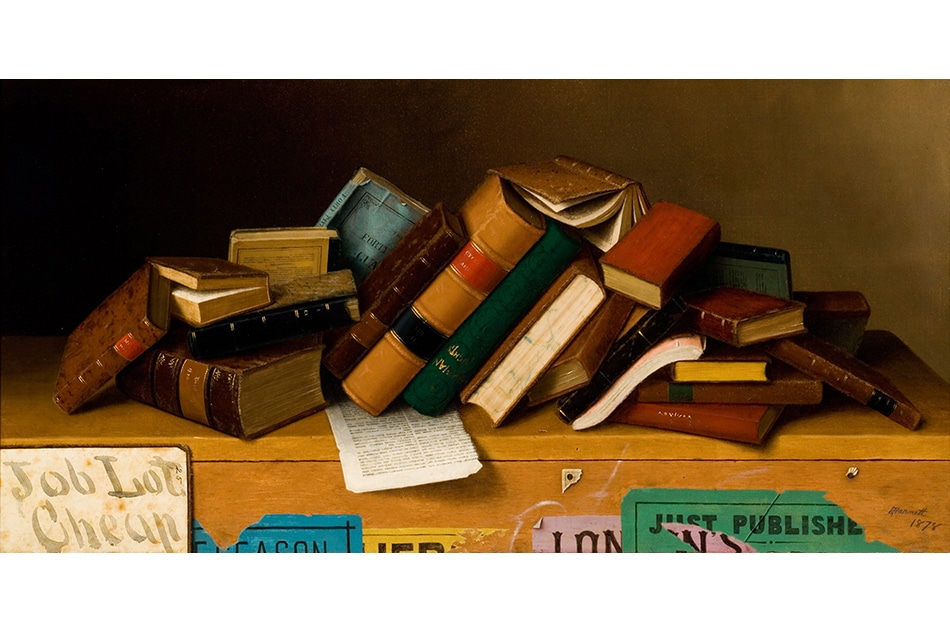

What she calls her “starting nine” paintings were the following: Church’s The Andes of Ecuador, 1855; Gilbert Stuart’s Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis (Sally Foster), 1809; Albert Bierstadt’s Sierra Nevada, 1871–73; William Harnett’s Job Lot Cheap, 1878; William Merritt Chase’s In the Studio, 1884; Joseph Blackburn’s Elizabeth Browne Rogers, 1761; Martin J. Heade’s Orchid with Two Hummingbirds, 1871; Eastman Johnson’s The Storyteller of the Camp (Maple Sugar Camp), 1861–66; and Childe Hassam’s Giant Magnolias, 1904.

Quite a lineup for a first at bat.

Georgia O’Keeffe is framed by her own spiral statue on the grounds of her New Mexico estate, Abiquiu. The photo, taken by Bruce Weber, appears in the traveling exhibition “Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern,” opening at Reynolda House on August 18.

“What I wanted to do was collect the highlights of American art,” says Millhouse. “It was not to make a comprehensive collection. We wanted to provide an educational background for tourists and people who came through the house.”

She went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to gather ideas. “Thomas Hoving had just come in as head,” Millhouse recalls. “I asked if he would allow Stuart Feld, then a curator of American art, to advise us on putting together a collection.” The answer was yes. “During that first year, I learned a lot from him,” she says. “He was tremendously helpful.”

Feld, now the owner of the venerable gallery Hirschl & Adler, says he had faith in Millhouse. “I knew her socially,” he explains. “I thought she was very smart. When she asked, I knew she’d have the determination and wherewithal to achieve her goals.” He also notes that the field was wide open: “There was so much more material available then.”

Interest in American art had yet to see a revival, and prices were relatively low. “Even the scholars of these artists didn’t have very nice things to say about them,” Millhouse recalls, adding that at the time, activists in the Hudson Valley were struggling to save Church’s magnificent estate, Olana. (The artist’s vast Andes was her very first purchase.)

Millhouse was able to sweep into the likes of Kennedy Galleries, the famed American art purveyor that now operates as a private dealership, and pick up works by great names for a song. In the years since, due to her own generosity as well that of her family members and other donors, the collection has grown and grown.

Millhouse, a graduate of Smith College before she attended Parsons, has worked for years as an interior designer and took special pride in restoring the Reynolda interiors to their 1917 style. “All the furniture is original. It was decorated by Wanamaker’s,” she says, referring to the famed department store, which outfitted the place from top to bottom in European eclectic style, with reproductions of so-called Old English and French pieces from the 17th and 18th centuries.

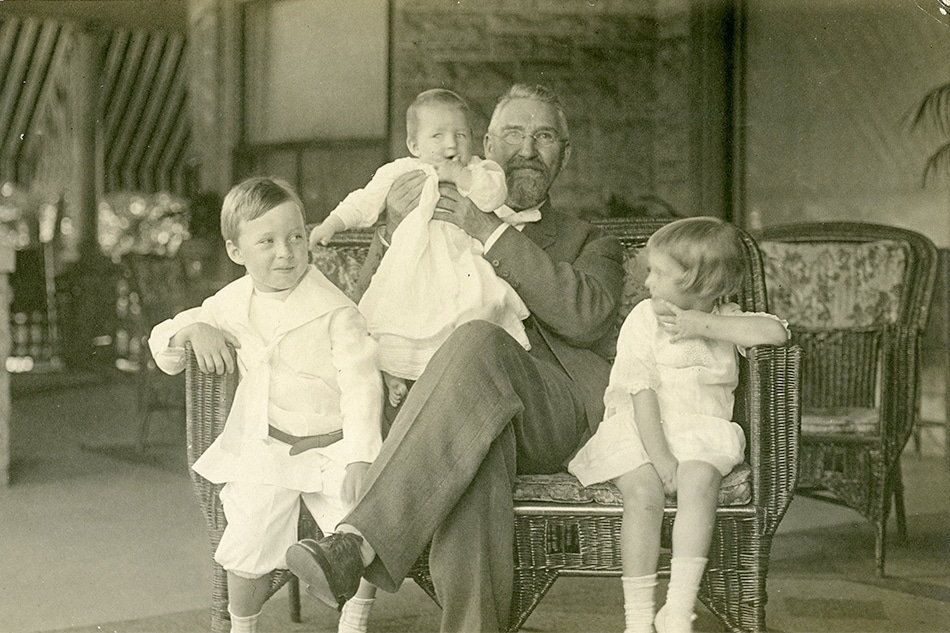

R.J. Reynolds built Reynolda House in 1917. Today, his granddaughter Barbara Babcock Millhouse continues to preserve his legacy through her thorough historical restoration of the property and ambitious program of American art. Portrait by Ken Bennett

Millhouse has also served as a trustee of the Whitney Museum of American Art and on the American painting and sculpture committee of the Met. Such service has helped hone a distinct point of view: “I feel strongly that museums should not show bad paintings by great artists.”

Her passion for specific works, not just the famous names behind them, has led her to reflect on the resonance of Reynolda’s treasures. “There are things that you don’t see in the beginning, but they reveal themselves over time, through scholarship or just looking,” Millhouse says. “Their messages change all the time.”

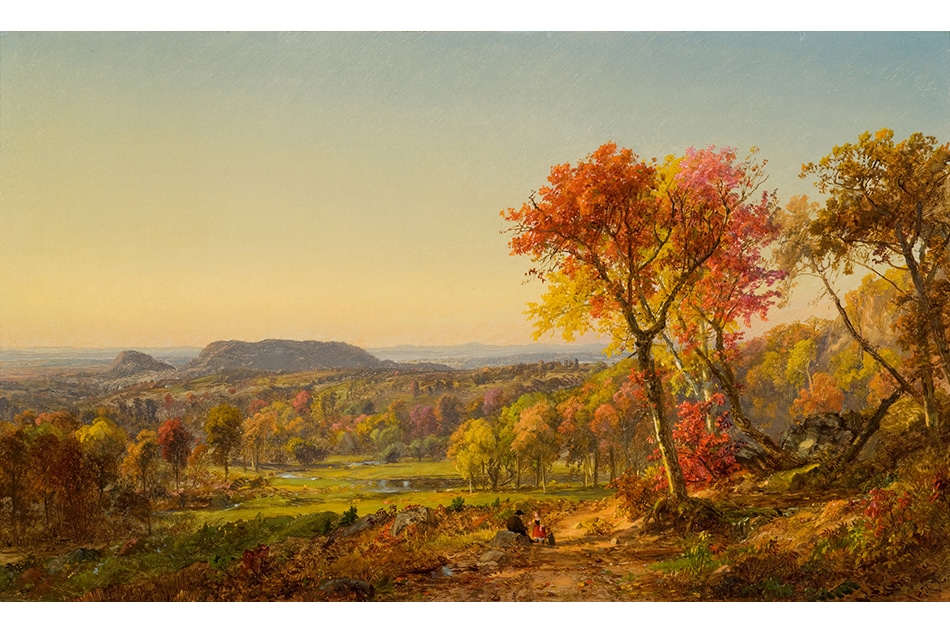

Lately, Jasper Francis Cropsey’s Mounts Adam and Eve, 1872, a brilliantly autumnal Hudson River Valley landscape painted in Warwick, New York, is particularly on her mind. When it was made, fall scenes were used to symbolize the maturing of American democracy. Cropsey was also influenced by Thomas Cole, whose series “The Voyage of Life” he explicitly references in the work.

“When I really studied it closely, I began to see that little stream in it, which turns into rapids,” Millhouse says. “Cole and other artists have used the river as a metaphor for life and the passing of time. That’s the obsession of the Romantic period.”

Thanks to Millhouse and her family, the passing of time has treated Reynolda very well indeed.