May 5, 2024I thought I knew all about Pablo Picasso. I consider my favorite Picassos in New York City museums like the Met, the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim to be old friends whom I visit often.

I’ve read John Richardson’s four-volume biography of Picasso, Françoise Gilot’s terrific My Life with Picasso and Hugh Eakin’s Picasso’s War. I knew he was a genius who dominated the art of the 20th century and a monster who ruined the lives of the women who loved him.

What did I really know?

Not as much as I’d believed, I realized when I did a recent tour of Picasso’s homes in Spain and the south of France.

Picasso (1881–1973) is often associated with the booming art scene of post-1900 Paris. While he did live in a half dozen apartments in Parisian neighborhoods like Montmartre and Montparnasse from 1900 to 1967 and developed his famous Blue, Pink and Cubist periods there between 1901 and 1919, the artist may have been most at home in the warm summer light of his native Spain and nearby southern France.

Here’s what I learned by experiencing firsthand the sites of Picasso’s various homes in those regions, including how they impacted his always-shifting style.

Childhood Apartment, Málaga, Spain, 1881–91

Picasso’s birthplace is Málaga, a prosperous city in the autonomous region of Andalusia, on Spain’s southern coast, which the ancient Phoenicians settled around the 9th century BCE and the Moors ruled for 800 years until 1487.

His family’s bourgeois apartment (now open to the public), overlooking the blooming jacaranda trees of the Plaza de la Merced, looks much the same today as it did in the 1880s.

Young Picasso lived in a household dominated by women: a doting mother, aunts, nannies and maids. As the only male heir of his generation in a huge family, he was treated like a prince and had learned how to manipulate women by the age of four.

The only time he seems to have spent alone with his father, a middling painter, drawing instructor and museum curator, was Saturday afternoons at Málaga’s famous bullfighting ring, still extant, which I discovered was a mere 13-minute walk from the apartment. Here is where Picasso’s lifelong obsession with bullfights began. In his work, the figure of the bull often represents him.

The seaside city’s crown jewel is the Museo Picasso Málaga, which was designed 20 years ago by minimalist New York architect Richard Gluckman, known for his many Soho gallery interiors.

Through March 2027, the museum is displaying “Pablo Picasso: Structures of Invention. The Unity of a Life’s Work,” which brings together 144 disparate works in an attempt to reveal how Picasso’s art changed across his eight-decade career. But as Picasso declared in 1923, “The several manners I have used in my art must not be considered as an evolution, or as steps toward an unknown ideal of painting.”

Picasso didn’t live in Málaga for long. When he was 10, his father lost his job and was forced to move the family to Coruña, a small town in Galicia where he’d found a new one. Unhappy on the cold, rainy, windy Atlantic coast, Picasso missed his booming hometown, its sunny beaches and bullfights, and henceforth identified himself as an Andalusian, although he never again lived there full time.

Rooftop Shanty, Barcelona, Spain, 1898–99

In Barcelona, I discovered that the inspiration for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon — the 1907 masterpiece that announced the birth of Cubism when Picasso released it from his tight Montmartre workspace — had nothing to do with young ladies or Avignon, France. The “Demoiselles” were the sex workers he patronized at a brothel at 44 Carrer d’Avinyó in what was (and still is) the city’s seedy red light district, where pickpockets rule the narrow, still-smelly streets.

Picasso was 17 and nearly destitute when he first lived in Barcelona. Here, I discerned that Picasso was tough, able to endure anything, including cold, hunger and poverty, as long as he could paint. At the local tailor shop, for instance, he traded his pictures for clothes.

During one Barcelona stay, he worked in a single-room studio built atop the roof of a small apartment house in the Gothic part of the city. Today, that apartment house has been replaced by the chic boutique hotel Serras Barcelona, where I visited a small rooftop bar that explicitly replicates the size of Picasso’s studio, with one identical square window.

Here, as elsewhere, I saw how clever Picasso was about his real estate choices. From the square window is visible the triumphant Madonna and Child bronze statue atop the Basilica of Our Lady of Mercy, a baroque cathedral; from the rooftop terrace you can see the currently packed marina, once home to the city’s shipyards, and the Mediterranean Sea.

The city-owned Picasso Museum, in the medieval quarter, opened in 1963 with 4,000 works by Picasso donated by his faithful secretary, Jaume Sabartés. In 1970, Picasso donated an additional 800 pieces.

The museum boasts a real treasure: 58 preparatory works that Picasso made in the 1950s as his tribute to Velázquez’s masterpiece Las Meninas, his fervor and passion evident in each iteration. (Picasso never put a title on any painting except Guernica. He said, “If you put a name on a painting, you change the condition of viewing it.”)

Villa Chêne-Roc, Juan-le-Pins, France, 1924 and 1931

After finding success in Paris in the early 1900s, Picasso could afford to explore the Côte d’Azur in the south of France, often in his showy, chauffeur-driven convertible. (Picasso refused to learn to drive, as he was fearful his hands might lose their “magic.”)

In 1931, now married to former Russian ballerina Olga Khokhlova and father to their son Paulo, he rented the manicured neo-Gothic Villa Chêne-Roc, which he had first seen in 1920, in the small seaside village of Juan-le-Pins, in the commune of Antibes.

The house was demolished in 1956, but Picasso had a special affinity for the hillside town covered in pine trees, saying “I don’t want to pretend to be a psychic [but . . .] everything was there. . . . I understood that this landscape was mine.”

He did a memorable oil-on-canvas painting of the pink villa on August 18, 1931. An Antibes museum curator told me that every time Picasso moved, the first thing he did was sketch the new place so he “owned” it, even as a renter.

Grimaldi Castle, Antibes, France, 1946

Picasso returned to France’s southern coast most summers. In 1946, now with mistress Françoise Gilot, he got permission to rent the massive Grimaldi Castle for a few months as a temporary studio.

This Gothic fortress was built in the 14th century on the ramparts of Antibes as a residence for Monaco’s ruling family, who owned it until 1608. The city of Antibes bought it in 1925 and turned it into an archeological museum.

Picasso was very prolific during his time there, and when he moved back to Paris later that year, he left a lot of work in the custody of the château. Here, I could see clearly, his muses included the local catch: octopuses, squids, sea urchins and moray eels.

In 1966, Grimaldi Castle became the Picasso Museum with his donation of 23 paintings, 44 drawings and 78 ceramics. In 1972, the year before he died, the museum organized a show of the artist’s late paintings (still on view), which revisited old themes — musketeers, matadors, dwarfs, pregnant women — but expressed with much looser brushstrokes. Piqued by bad reviews at the time, Picasso retorted, “You have to know how to be vulgar, to paint with swear words.”

In Antibes, I adopted a favorite Picasso pastime: the ceremony of absinthe tasting, for which you wear a hat, eat tapenade, made of olives, anchovies and capers, on bread and play cards.

I also learned that bartenders may serve only three rounds per customer; if you want to keep drinking you must find another bar! I was told that Picasso was not a serious drinker. Work, sex and tobacco were his addictions.

Villa La Galloise, Vallauris, France, 1948–55

Vallauris, a seaside commune in Antibes on the Côte d’Azur famous for its bitter orange trees and the oil derived from their blossoms (a key ingredient in Chanel No. 5 perfume), is where Picasso lived from 1948 to ’55, an extremely fertile period of artistic creativity. The Picasso family still owns his humble house there, dubbed La Galloise. It is not open to the public, but Vallaurisians celebrate his years in the town.

Here, in 1952, Picasso made technical experiments with ceramics, linocuts, sculpture and painting, including two 40-foot-long murals depicting war and peace in the vaults of the former priory of the Abbaye de Lérins. In 1977, the site became known as the National Picasso Museum: War and Peace.

In 1950, Picasso began working with nearby pottery manufacturers, designing 4,000 original ceramics in editions that eventually monopolized most of the local ceramists. “It took me a lifetime to learn how to draw like a child,” he said of his deceptively simple-looking pottery etchings.

The Ceramics Museum in Vallauris has several of Picasso’s early clay creations on display, and their naive charm is enchanting.

Although he was still with Gilot at the time, Picasso met his second wife, Jacqueline Roque, at a Vallauris ceramics factory where she worked. After Gilot left him, he married Roque in 1961 in the town hall.

Mas Notre Dame de Vie, Mougins, France, 1961–73

Picasso died in 1973 in Mougins at Mas Notre Dame de Vie, an idyllic 35-room villa he bought from the Guinness beer-making family as a wedding present for Roque. Much larger than a traditional Provençal farmhouse (mas), the home had a studio room with untreated limestone walls, which were probably cool during the hot summer days.

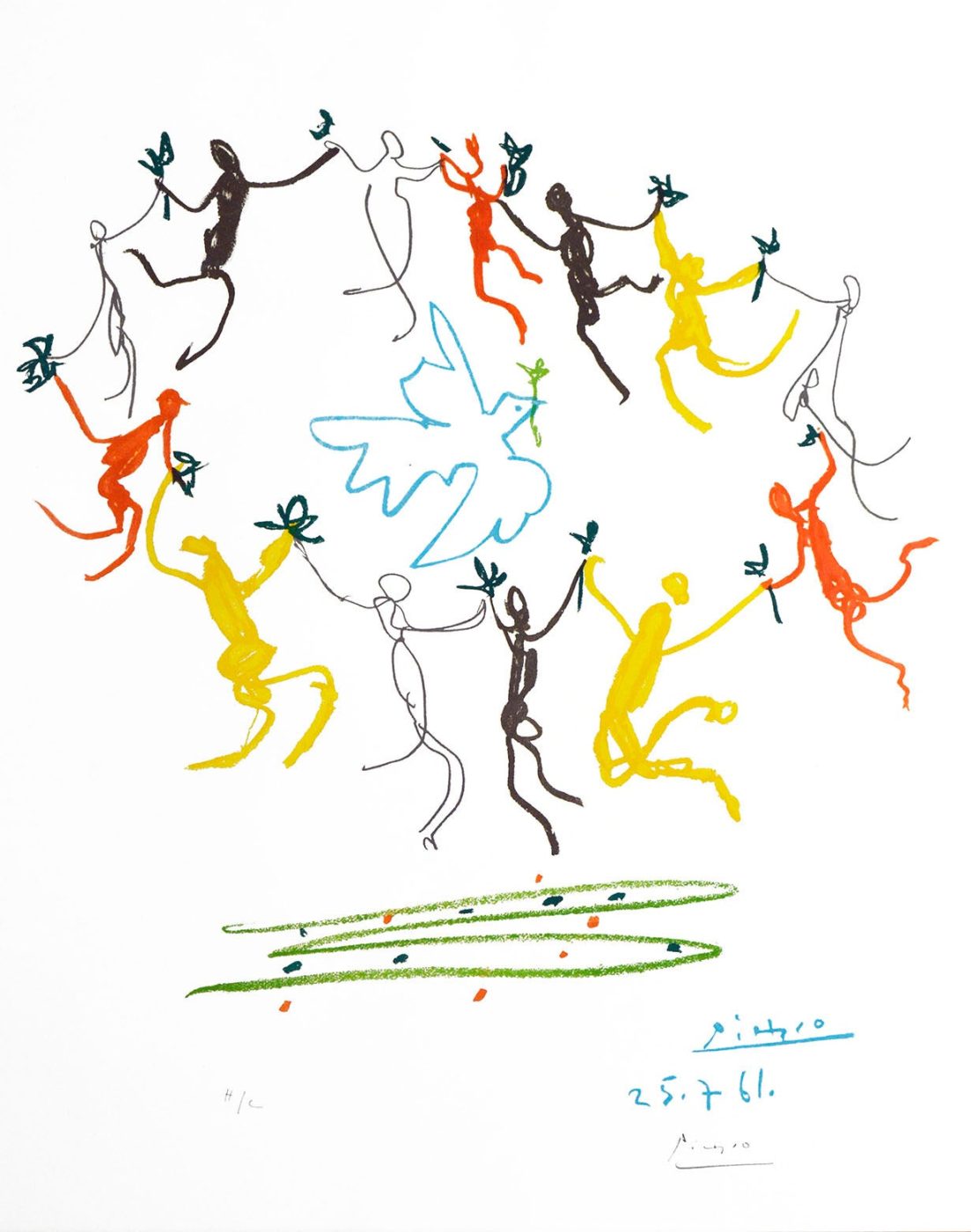

In any case, Picasso was incredibly prolific there. Among his more renowned pieces produced at Mougins are La ronde de la jeunesse, 1961; Nu assis dans un fauteuil (II), 1963; and Femme nue couchée au collier, 1968, a portrait of Roque.

In fact, during the 20 years Picasso and Roque were together, he made 400 drawings and paintings of her, producing 70 portraits in just one year, more than he had done in his whole time with either Dora Maar or Gilot.

The estate is in private hands today, the current owner unknown. In 2015, the Belgian antiquaire and decorator Axel Vervoordt was hired to restore it, which he did with the help of 200 workers over the course of two years. His client then put it up for sale for $24 million.

Happily, the 17-acre estate can be viewed from the grounds of its hilly next-door neighbor (and namesake), the picturesque 12th-century Chapelle Notre Dame de Vie, which over the years has attracted many illustrious visitors, including Mstislav Rostropovich, Jean Cocteau, Charlie Chaplin and Winston Churchill.

It seems fitting that this protean genius, who spent his early years in Barcelona and Paris in studios without heat, running water, furniture or electricity, lived his final days in this lush, quiet enclave.

And, yes, he never stopped working. He was organizing a new exhibition the week before he died, at the age of 91.