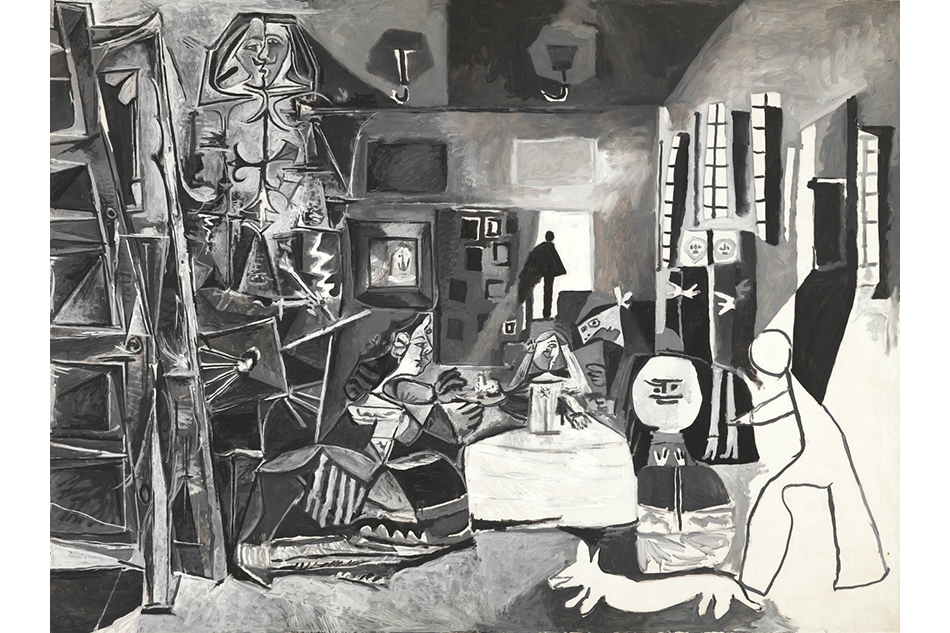

November 21, 2012“Picasso Black and White,” on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, in New York, through January 23, 2013, fills the famous rotunda (top) with 118 largely monochromatic artworks by Pablo Picasso. Accordionist, 1911 (photo by Kristopher McKay © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation). (photo by David Heald © 2012 Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation). All images © 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

When the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s latest blockbuster, “Picasso Black and White,” took up residence last month in the New York cultural center’s Frank Lloyd Wright–designed rotunda, the occasion marked the eighth major exhibition that Carmen Giménez has devoted to the protean artist’s work. The museum’s Stephen and Nan Swid curator of 20th-century art, Giménez counts among her other accomplishments “The Century of Picasso,” first seen in Paris in 1987 and then at the Reina Sofía, Madrid’s museum of modern and contemporary art, which Giménez helped create; “Picasso and the Age of Iron,” a sculpture show held at the Guggenheim in 1993; and 2003’s “Picasso’s Picassos” at the Museo Picasso Málaga, of which she was the founding director.

Don’t be mistaken, however: Giménez is no one-trick pony. At the Guggenheim she has curated critically acclaimed exhibitions on David Smith, Richard Serra, Alexander Calder and Cy Twombly, among others. Those last three were held in the museum’s wildly popular Frank Gehry–designed satellite in Bilbao, Spain, the creation of which Giménez, then a Madrid-based consultant to the museum, played a key role in.

But it is with Pablo Picasso, whom Giménez says “opened the twentieth century to a new way of seeing,” that she has the deepest affinity. “As the Spanish daughter of an exiled Republican,” she writes in her essay for the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition, “I have been marked by the figure of Picasso and the example of his political commitment since my childhood — even before I was able to appreciate his immense artistic value.”

That value is evidenced in the more than 100 black, white, gray or monochrome paintings, drawings and pieces of sculpture that comprise Giménez’s latest outing with Picasso, on view at the Guggenheim, in New York, through January 23, 2013. Just prior to the show’s installation, she sat down with Introspective’s Anthony Barzilay Freund to discuss the great Spanish painter as well as highlights from her own distinguished career. (A version of this story first appeared in Sotheby’s At Auction magazine.)

Man with Pipe, 1923. Photo by Eric Baudouin

ABF: Is it possible for a curator to ever run out of things to say about Picasso?

CG: No, I don’t think so. There are certainly many other shows I could do. But you have to have a good subject. If not, people are no longer willing to loan their works. But people who know me very well — museum curators, the family of Picasso and Picasso-lovers — have been aware that I have had this idea for a long time. So that did help me very much in securing the works I wanted.

ABF: Most museum exhibitions are several years in the making. How long have you been thinking about “Black and White”?

CG: I first had the idea in 1979, when the estate of Picasso presented at the Grand Palais the works from his personal collection; these would ultimately go to the Musée National Picasso, Paris. Because Picasso kept the things he loved for himself, I made so many discoveries in that exhibition. In addition to black-and-white paintings from all periods, collages and Cubist works, there was so much sculpture — he rarely exhibited his sculpture, so it was not well-known. And I saw a lot of monochrome going on.

ABF: Your relationship with his personal cache continued when you opened the Museo Picasso Málaga in 2003 with an inaugural show called “Picasso’s Picasso.”

CG: That exhibition featured works that belonged to the family — much of it from his daughter-in-law, Christine Ruiz-Picasso, and her son, Bernard, who generously gave works so Picasso could have a museum in his hometown. And in one room I installed the black-and-white pieces and in another, the color.

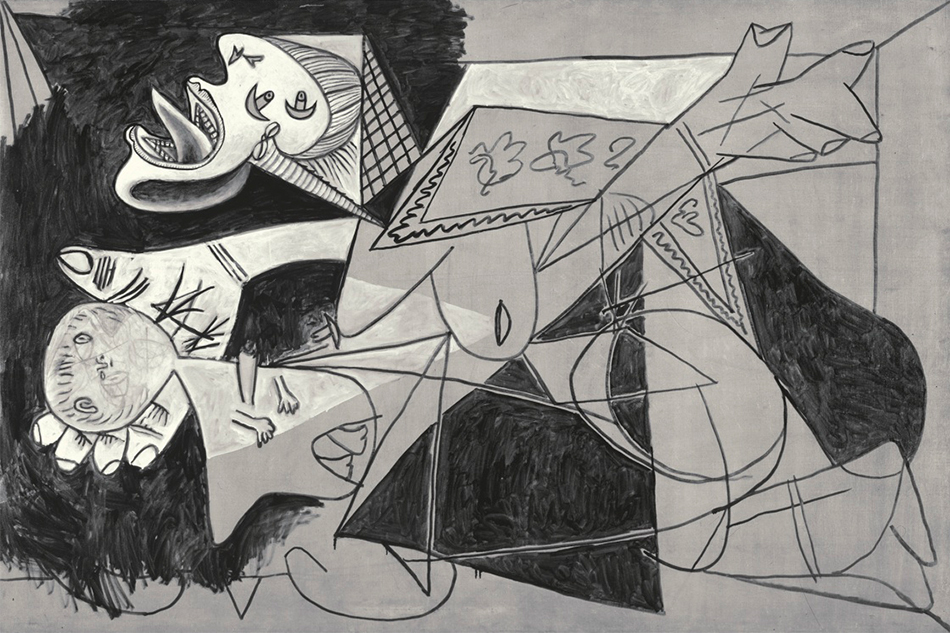

Head of a Horse, Sketch for Guernica, 1937. Photo © Archivo fotográfico Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

ABF: So you were rehearsing the installation of the Guggenheim show nearly a decade ago! How do the sculptures play into your black-and-white theme?

CG: Picasso loved the plasters. In the 1930s he owned a very interesting château, Boisgeloup, where he worked long into the night in a studio lit by candlelight and gas lamps. And he loved to see those white plasters together in that light. That’s why those famous photos of the studio by Brassaï are so essential [to understanding Picasso’s relationship to this palette].

Picasso showed these works in 1932 at Galerie Georges Petit; it was the first time he had a big show in Paris. And he did the installation himself: On one end of the gallery was an iron statue called Man — it’s black, of course; he’s the color of iron — and opposite that he placed another sculpture called Woman, and it’s painted white.

ABF: I see that you’ve included images of these works in the catalogue though they’re not in the show.

CG: Yes. They came here for the Guggenheim’s sculpture show “Picasso and the Age of Iron,” so I did not really want to ask for them again. But I have managed to assemble a beautiful group of sculptures, one of which for me is very symbolic. It’s the iron cast of Woman with a Vase, 1933, which he made for the entrance to the Spanish Pavilion [of the Paris Exposition of 1937], with Guernica inside. This woman with a vase, she was a receiving woman at the entrance to the pavilion, and at the time she was cast in cement, because plaster was very delicate.

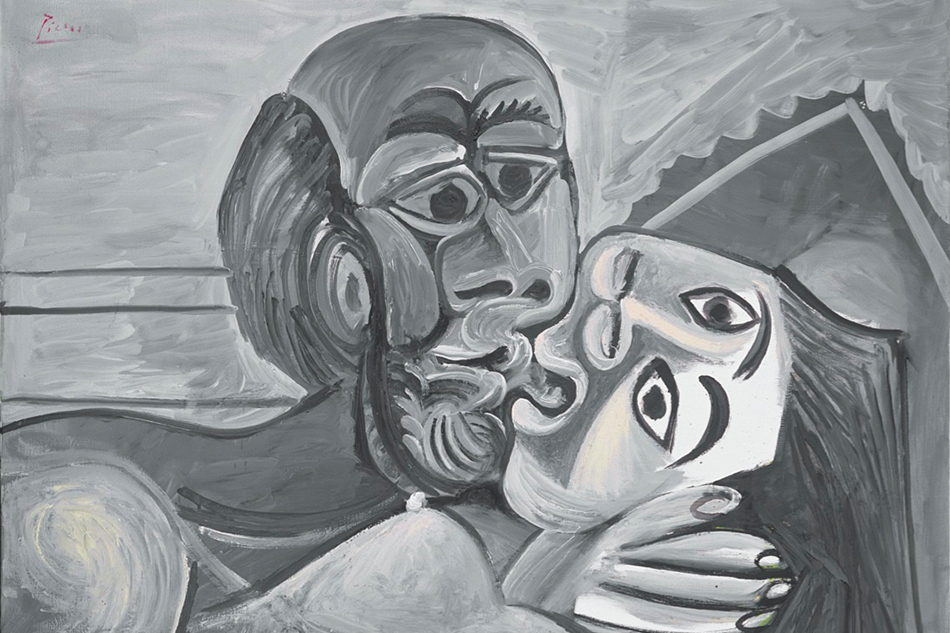

Marie-Thérèse, Face and Profile, 1931. Photo by Béatrice Hatala

ABF: What is the story behind this version of the sculpture?

CG: When Picasso died, his widow, Jacqueline Roque, commissioned two casts: One guards his tomb at the Château Vauvenargues, in the South of France, and the other — this one — I had the honor of buying for the first Socialist government of Spain in 1987, when I was an adviser to the Minister of Culture, Mr. Javier Solana.

ABF: The Reina Sofía, of which you were the founding general director of the National Center of Exhibitions in 1986, has loaned her to the Guggenheim.

CG: And I have placed this Woman with the Vase at the entrance to the exhibition. She’s once again going to be the one who receives people.

ABF: Beyond her obvious symbolic appeal, what is her physical presence like?

CG: She is very, very tall and very strange. She comes from Iberian sculpture, which Picasso discovered before African art. Iberian sculpture was extremely important to his work at the time.

ABF: I’m shocked — shocked! — that the exhibition doesn’t include Guernica, her longtime friend and neighbor, which is undoubtedly Picasso’s most famous black-and-white painting.

Seated Woman in an Armchair (Dora), 1938. Photo by Robert Bayer, Basel

CG: First, I would never have tried [laughs]. I don’t think I’m crazy. And, honestly, if I were to get Guernica here, we wouldn’t need the rest of the exhibition! Anyway, you had the painting in New York for years at MoMA — in fact, I saw it for the first time here, and I must say I was very happy.

ABF: Were you involved in bringing it to the Reina Sofía?

CG: No, Picasso gave it to the Prado, and I think he would be very happy to still be in the Prado with Diego Velázquez and Francisco Goya, where he belongs. It came to the Reina Sofía in 1992, after I had joined the Guggenheim full time. But the Reina Sofía without the Guernica would be very difficult, because you need to have roots, you know. You need to start this collection of modern art somewhere.

ABF: And what better place than Picasso? You’ve talked about how he’s the soul of modernity. Do you still think he’s maintained his relevance today?

CG: Oh, yes, yes, yes. For me, he’s the most important artist of the twentieth century. Picasso brought everything to the table.

ABF: Just down Fifth Avenue, the Metropolitan Museum has a show on the continuing influence of Andy Warhol, that other titan of the twentieth century. Do you think there’s an ideological battle between the School of Warhol and the School of Picasso or do they coexist peacefully?

CG: Oh, I think they coexist. I don’t see battles. I think artists generally coexist. For instance, Picasso never had a battle with Henri Matisse. He loved Matisse. And certainly Matisse respected him.

Woman Ironing, 1904. Photo by Kristopher McKay © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

ABF: You helped bring the Guggenheim to Bilbao. It’s remarkable how the Frank Gehry–designed satellite continues to attract so many visitors, not all of them necessarily art lovers.

CG: But that’s true in New York, too. Not only art lovers come to see the Frank Lloyd Wright building.

ABF: In terms of curating or installing shows, do you have a preference for Bilbao or New York? Gehry’s galleries are much bigger and offer more flexibility.

CG: You know, I love Frank Lloyd Wright and the rotunda. And I think this show would not have been the same elsewhere. Here, you see the show from the top on down; you see the full spectrum. Plus, it’s a white museum!

ABF: Exactly, it’s white with this perfect rhythm of black bands. Which brings us back to the theme of your show: Why do you think this palette was so compelling to Picasso?

CG: I think he really didn’t care about color. He cared about the form and the structure of the painting. He wanted to express himself in the best way possible. I have started the show with Woman Ironing (1904), from our own collection. And although it’s from his Blue Period, it’s mostly grays, very monochromatic. And from his Pink Period, we have Man, Woman and Child (1906), and it, too, shows how Picasso really used very little color.

Picasso in his Paris studio on the Rue des Grands-Augustins in front of The Kitchen, 1948. Photo by Herbert List/Magnum Photos

In Françoise Gilot’s fantastic book, My Life with Picasso, she recounts a conversation in which Picasso said, “If you take the blue or the red or the main color out of a Matisse, the painting collapses. But if you take out one color in my painting, the structure is still there.”

For him, color was a distraction. He has the power to bring you into his field without using color, because he’s a master drawer. The line is what’s powerful in his work.

ABF: I keep thinking about all his beautiful, voluptuous curves, and how they play off the curves of the Guggenheim. That said, do you think that in this post-Technicolor age, museumgoers need to see bright colors, neon lights, flashing screens, polka dots, butterflies?

CG: They are getting to see in this show what a beautiful draftsman Picasso was. He had the power to interest you without the color. Of course, when he wanted to be, he was a magnificent colorist.

ABF: So if visitors to your show want a jolt of color afterwards — a sweet dessert, so to speak — to what painting would you direct them?

CG: His Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, at MoMA, which is one of the major paintings of the twentieth century. That has color, lovely color.