December 8, 2024The Brooklyn Museum’s sprawling exhibition “Solid Gold,” a glitzy tribute to the precious metal on view through July 2025, underscores, above all, gold’s enduring grip on the human psyche. Across eras, cultures and geographic expanses, our species has gone to great lengths to possess, transform, wear and display the material. And the fixation shows no signs of diminishing.

The show includes more than 500 objects, spanning more than 30 centuries and nearly every continent. Ancient artifacts, haute couture gowns, Renaissance altarpieces, Japanese screens, modern-day jewelry and watches, historical decorative arts and contemporary artworks and ephemera come together to paint a picture of the human fascination with gold.

Through it all, the metal’s allure seems to be as much about the visual pleasure of its glint and glow as the wealth and prestige it has long communicated. And then, there is its connection to divinity. “Gold transcends its materiality, carrying relational, spiritual and monetary meanings so profound that it is impossible to consider it merely as a metal,” says Matthew Yokobosky, the museum’s senior curator of fashion and material culture.

When it was first discovered, in streams and rivers millennia ago, says Yokobosky, “many believed its creation stemmed from the union of golden sunlight and water.” Over time, that belief blossomed into a full-fledged association with divinity and power.

Our understanding of the world might be more scientific now, but gold still feels and looks special, making it a fitting subject for the museum’s bicentennial celebration this year — and a good excuse for Yokobosky and his cocurators, Catherine Futter and Lisa Small, to pull all kinds of rarely exhibited treasures out of storage. A finely tooled laurel wreath from Corinth, Greece, from the 3rd to 2nd century B.C.E. is a good reminder of the material’s staying power. “Pure twenty-four-karat gold is soft, yet it endures due to its resilience, immune to corrosion or rust,” says Yokobosky.

The museum’s holdings were supplemented with loans from other museums and fashion and jewelry houses. There is no shortage of sumptuous vintage jewelry by Cartier and embellished looks by Dior (an exhibition sponsor), Mary McFadden, Yves Saint Laurent, Gianfranco Ferré and Balenciaga. Through Marc Bohan’s dramatic 1962–63 black-and-gold Aladin ensemble for Christian Dior, we’re reminded how readily gold lends itself to fantasy. And that seems to be a large part of its enigmatic appeal.

It’s surprising to learn that although some of the works on view are actually solid gold — like an 18-karat-gold sculpture of supermodel Kate Moss in a yoga pose — most have relatively little real gold content.

And that’s partly what makes the exhibition so captivating.

Driven by the rarity and cost of gold, clever craftsmen have long experimented with ways to make a little go a long way. This show is not a collection of priceless gold objects but rather a survey of how creative we’ve gotten with the material.

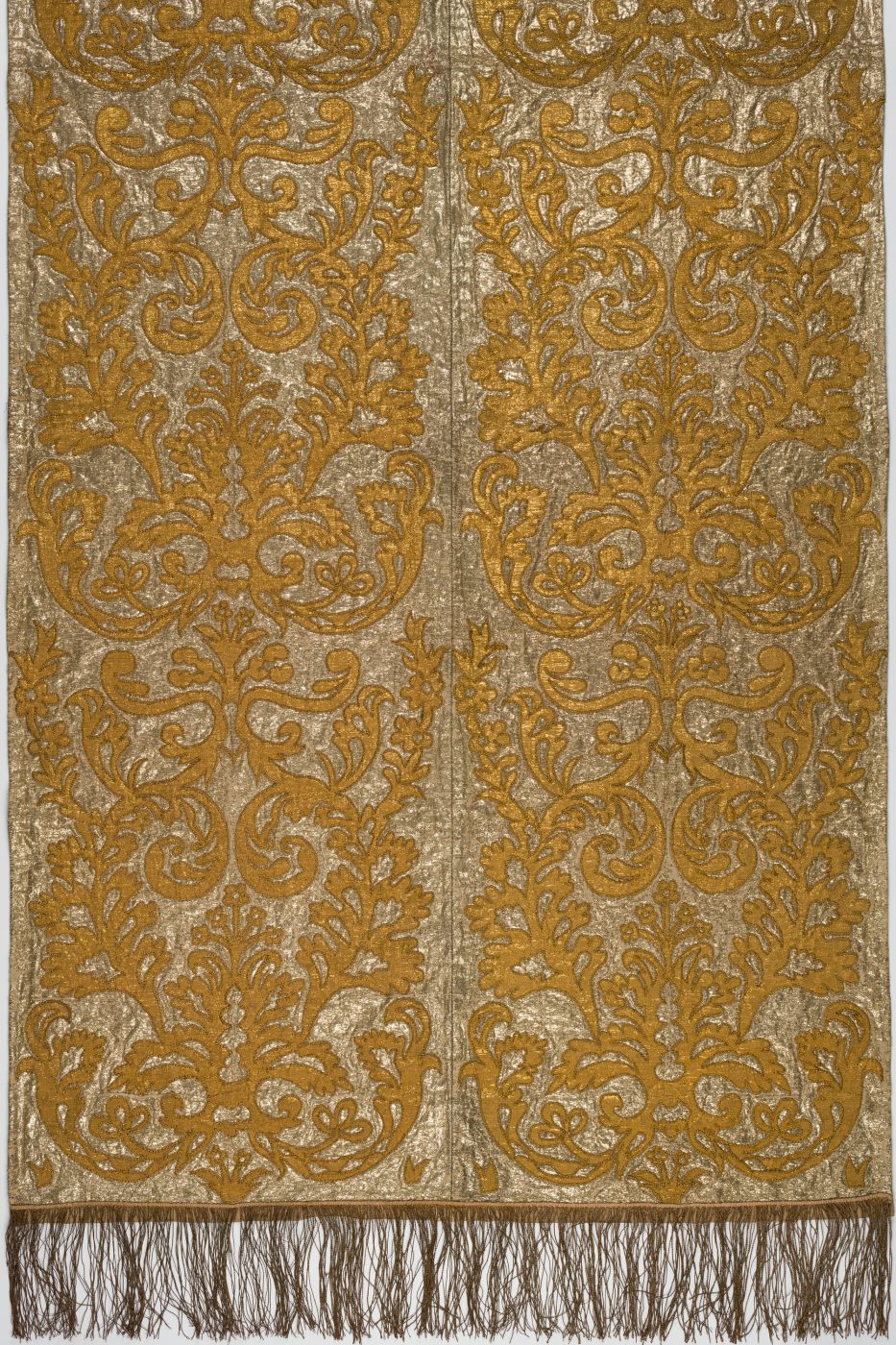

“The atomic structure of gold is very symmetrical,” says Yokobosky. “This is the reason you can keep pounding it down and make it thinner and thinner and produce things like gold leaves.” It could also be pulled into wires to make filigree jewelry and accessories, pulverized into powder to make pigment and used to cover threads woven into textiles. Such technical innovations are visible throughout.

The metal, we learn, became more broadly accessible with the circulation of gold coins. (The earliest example here is from 283–246 B.C.E. Egypt.) Artisans began to hammer the coins into sheets, which they used to cover wood, bronze, porcelain and other more mundane materials. Gold grounds gave devotional paintings and altarpieces a near-mystical luster. Giltwood furniture, meanwhile, conveyed a richness suitable for 18th-century European palaces and 19th-century American mansions.

Before the invention of electricity, that golden shimmer was both a sound practical and aesthetically pleasing solution to darkness, since the glow could amplify the light of a flame. Louis Comfort Tiffany’s shimmering favrile glass — made by mixing metallic particles with molten glass, a process he invented and patented in the early 1890s — must have magically transformed a dim space as it caught the light.

Creative applications of the metal surged in the 1920s and ’30s, thanks to the era’s taste for all things luxe and glittering. Cartier, for instance, used a complex tinting process to craft elegant cigarette cases in red, pink and green shades of gold, while Suzanne Belperron hammered 22-karat gold into sculptural forms from nature. Elsa Schiaparelli embraced gold plating to make chic mesh purses for modern women out on the town.

The extraordinary craftsmanship and high style of Art Deco is epitomized by the work of French designer Jean Dupas, who revived the labor-intensive antique process of verre églomisé — painting the rear side of a piece of glass with gold leaf — to create sumptuous decorative panels for the Normandie, an ultra-luxe 1930s ocean liner.

In the late 1930s and ’40s, as a weary America sought distraction, the glamour and glitz of gold made an especially robust showing on the silver screen. The exhibition includes a fantastic clip of the country’s favorite wartime pinup, Rita Hayworth, twirling in a flowy golden gown in the 1944 film Cover Girl. It’s a million miles away from the Depression and World War II.

Around the same time, the need to find more practical and economical ways of working in gold yielded the invention of Lurex, a synthetic metallic yarn popularized by the colorful weavings of mid-century textile designer Dorothy Liebes. “It gave a layer of glamour and drama and brightness to her designs,” says Yokobosky.

By the 1960s, fashion pioneers like Cristóbal Balenciaga, in Spain, and Norman Norell, in the U.S., were stitching metallic sequins onto evening gowns, while jewelry designer Antonio Lopez was harnessing gold plating to create chic, chunky pop costume jewelry that would be far too heavy to wear if it were solid gold.

We see gold hit its ultra-glam stride in the 1970s and ’80s with the disco-inspired fashions of Halston. The exhibition channels that vibe through a slideshow of photos by celebrity photographer Ron Galella of legendary model and singer Grace Jones performing at Studio 54 in gold lamé.

There’s an undeniable celebrity presence across the show — in photos, magazine covers, film clips, videos and objects. Near Grace Jones is a video of hip-hop artist Missy Elliott performing on stage at her Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony in a gold sequined suit designed by the Blonds, an American fashion duo known for outfitting celebrities in ultra-glam ensembles. They’ve got more than a dozen pieces on view here, including their 2019 Super Freak head piece, a gold-toned metal-rope-and-rhinestone wig inspired by Cleopatra and Rick James, worn by actor and recording artist Janelle Monáe on the cover of Rolling Stone in June 2023.

There’s a circa 1978 Norman Parkinson photo of Charlie’s Angels’ Cheryl Ladd in a gold gown by Bob Mackie and a 1966 Richard Avedon photo of Barbra Streisand wearing Lopez cube earrings for a story in American Vogue.

Elizabeth Taylor makes several enchanting appearances. It’s especially fun to see her in head-to-toe gold as the Egyptian queen Cleopatra in the 1963 epic film of the same name, a look that became a defining aesthetic of that decade.

It’s also a treat to stumble on the gold-beaded Azzedine Alaïa–designed minidress that Tina Turner shimmied in during her 1989 world tour and the gold tulle-and-rooster-feather Égalité gown designed by Maria Grazia Chiuri for Dior and worn by French pop sensation Aya Nakamura during her opening-ceremony performance at the recent Paris Olympics.

Although fashion and jewelry dominate the exhibition, there’s an exceptional selection of contemporary art, as well, including works by Jean-Michel Basquiat, David Hockney, Nam June Paik and Imi Knoebel.

Two of the most magnificent showstoppers, Yves Klein’s 1961 Untitled (Monochrome) and Agnes Martin’s monumental 1963 painting Friendship, are both abstract gold-leaf-covered surfaces. And both, through the sheer brilliance and beauty of the material, come remarkably close to the otherworldly.

But gold is, in fact, utterly connected to the earth — a geological marvel formed far beneath the planet’s surface long before humans existed. That it is at once terrestrial and ethereal, ancient and everlasting, seems reason enough for it to command our enduring fascination.