March 27, 2017Partners in an eponymous New York–based architecture firm, Dana Tang and Richard Gluckman have carved out a specialization in exquisite spaces designed to show art, be they museums, galleries or private homes (portrait by Claire Holt). Top: The lap pool of a Sonoma, California, home designed for tech entrepreneur Tim Mott overlooks the property’s vineyards and oak trees (photo by Bruce Damonte).

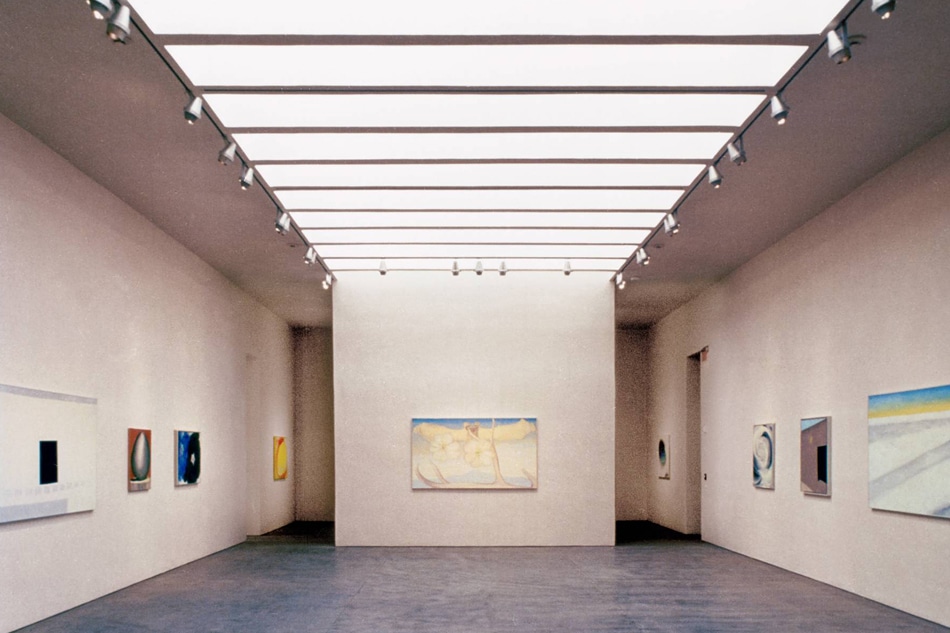

Architect Richard Gluckman is known for creating exquisite places to show art. Among his first major commissions was the Dia Center for the Arts, a renovation of a 40,000-square-foot warehouse space in New York’s Chelsea district. When it opened, in 1987, he says it really put him “on the map.” In the decades that followed, he designed many cultural institutions, ranging from the Mori Art Museum, a showplace atop a 53-story building in Tokyo; to the Museo Picasso Málaga, in Spain, a sublime combination of old and new; to the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, where he took his cues from the artist’s own adobe studio; to the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Back in New York, he designed spaces for such blue-chip galleries as Gagosian and Paula Cooper. And he became the go-to architect for wealthy collectors looking for museum-quality spaces in their homes. One hired him to design a pavilion for viewing a collection of Isamu Noguchi sculptures, then another to house a dozen works by the minimalist artist Walter De Maria.

So it’s not surprising that Gluckman would have plenty of work in China, a country currently constructing hundreds of new museums. It helps that he has a Chinese-speaking design partner, Dana Tang. That’s a happy accident, however. “I’m Chinese-American, but I did not grow up speaking Chinese,” says Tang, a native Manhattanite. She learned Chinese as a University of Colorado undergraduate, in grad school at Harvard and in a summertime immersion course at Middlebury College.

These days, their firm, Gluckman Tang Architects, is working on four museums in China, three of which are expected to open this year. One is a 270,000-square-foot teaching museum at Zhejiang University, in Hangzhou, modeled on those at American colleges. Tang’s collaborators on the project include her uncle Wen Fong, the former chair of the Department of Art and Archaeology at Princeton University and the former Consultative Chairman of the Department of Asian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Museo Picasso Málaga’s walled garden incorporates several fountains and sits adjacent to Málaga’s historic palacio. Photo by David Heald

But there is another side to the firm that Gluckman founded 40 years ago. (Tang, who has worked with Gluckman for more than 20 years, became a name partner in 2015.) It has completed a number of residences where art isn’t the focus. Take the house in Sonoma that Gluckman created for tech entrepreneur Tim Mott. The design draws inspiration from three things no artist could create: the movement of the sun across the property, the local prevailing winds and the inspiring views of nature provided by the setting. Gluckman gave the house a strong central axis, embodied by a kind of breezeway that leads directly from a guest house and studio suite to the dining room of the main house. From there, it proceeds to a terrace that offers glimpses of the San Francisco skyline, some 40 miles to the south. “You have to know when to hang a picture on the wall and when to let the view be the picture,” he says.

One of Gluckman’s calling cards is his own house, on the North Fork of New York’s Long Island, where a roof deck on the second floor steps up to become a viewing platform behind parapet walls. Not long ago, a couple with property in Bridgehampton saw photos of that house and asked Gluckman for something similar. The architect created two volumes — one containing living spaces, the other bedrooms — linked by a hallway of translucent “channel glass.” Off the master bedroom is a partly enclosed deck that gives the owners privacy. It then connects to an upper deck, like the viewing platform at Gluckman’s home, offering views of the water, says Gluckman.

Richard Gluckman became the go-to architect for wealthy collectors looking for museum-quality spaces in their homes.

Gluckman used a lot of wood inside the Bridgehampton house, even covering the living room’s high ceilings with the same white oak as its floor. Visually merging the floor and ceiling makes the tall room feel comfortable, he says, admitting he got the idea from Donald Judd. (The wooden ceiling of Judd’s fourth-floor living room in SoHo was a “brilliant addition” to the artist’s house, “implying a planar volume often found in his sculptures,” the New York Times’s Roberta Smith has written.) Elsewhere in the Bridgehampton home, Gluckman used as little drywall as possible, not just because he dislikes it but because all-wood houses recall traditional beach cottages, built back when drywall didn’t exist and plaster was prohibitively expensive.

Gluckman did, however, create a few walls with the material, which he generally deployed as white backdrops for brightly colored paintings. “The house wasn’t designed around a specific collection, but it was designed knowing the clients had a collection,” Gluckman explains. The boldness of their paintings, he adds, is tempered by the muted landscape visible from every room.

Tang entirely reconfigured the floor plan of the Tribeca loft to maximize views and daylight. The chairs are by Jens Risom. Photo by Bruce Damonte

For her part, Tang says the firm’s hallmark is reducing spaces to their bare essentials. “We care about proportions and light and materials — the feeling a space gives you — and we try to eliminate things that distract from that,” she says.

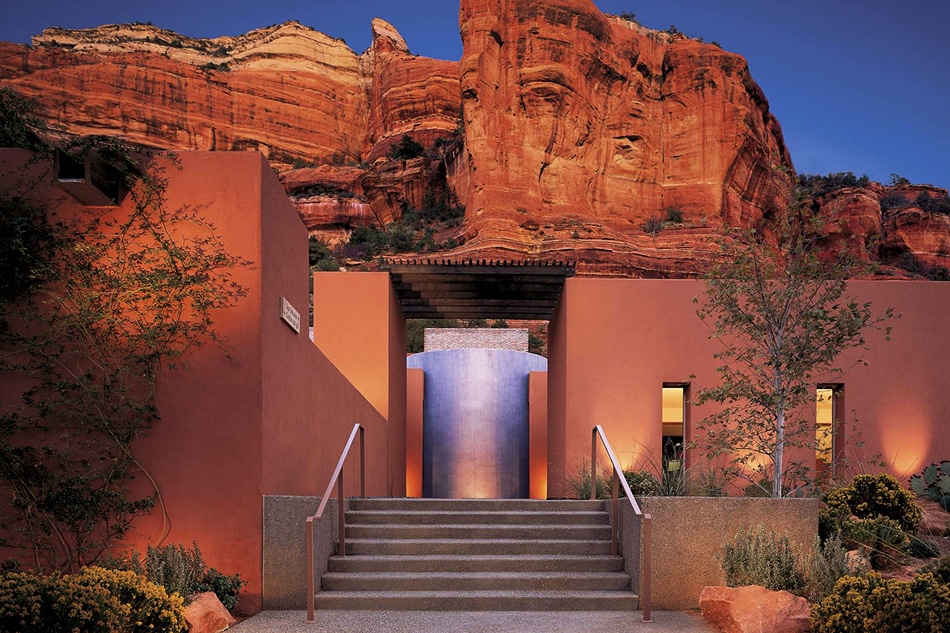

Tang’s early projects for the firm ranged from a spa in Sedona, Arizona, to an art studio in Maine. Now, in addition to museums and galleries, she too designs houses and apartments. One standout residence is a condo in a former icehouse (that is, a refrigerated warehouse) in Tribeca, where the goal was to preserve the original architecture while inserting contemporary living spaces. Tang retained the building’s vaulted ceiling, she says, “not just because it gives height to the space and reflects light beautifully, but because highlighting the original structure was important to us, as it is in many of our art-related projects.”

Reorganizing the floor plan, Tang worked to make the most of the condo’s large windows. In particular, she moved what had been an internal kitchen toward the unit’s southwest-facing wall. “We went through a lot of gymnastics to get the plumbing and the gas lines there,” she says. The result is a sleek but functional kitchen. High-gloss cabinetry bounces sunlight around the room, and floors of dark walnut provide contrast with pale-hued Caesarstone countertops in an unusual honed finish. The architect chose a David Weeks ceiling fixture for the room in part for its asymmetry, which allowed her to reconcile the unmovable bays of the vaulted ceiling with the geometry of the new kitchen.

To separate the living and dining rooms, Tang customized a Molo Softwall — a paper wall that “accordions” out to form a partition but disappears entirely when not in use. “You can wrap the dining table in a cocoon or divide the overall space in half,” she says.

Customization continued into the master bedroom, with bookshelves and night tables (and a fabric-covered headboard Tang created in collaboration with interior designer Eric Alch). One challenge, she says, was accommodating all the owners’ electronics. So the tops of the night tables slide forward, creating discreet slots for power cords.

The goal of all her interventions? To enhance the architecture, not to obscure it. As in all Gluckman Tang’s work, she says, “we really want the fundamentals of the space to be readable in the final result.”

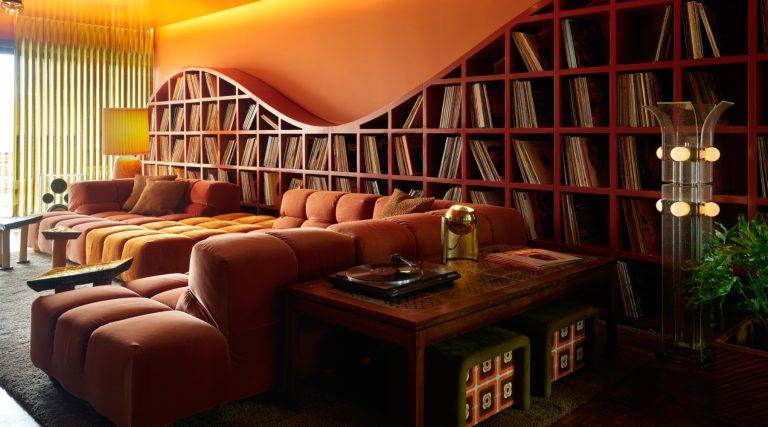

Richard Gluckman’s and Dana Tang’s Quick Picks on 1stdibs