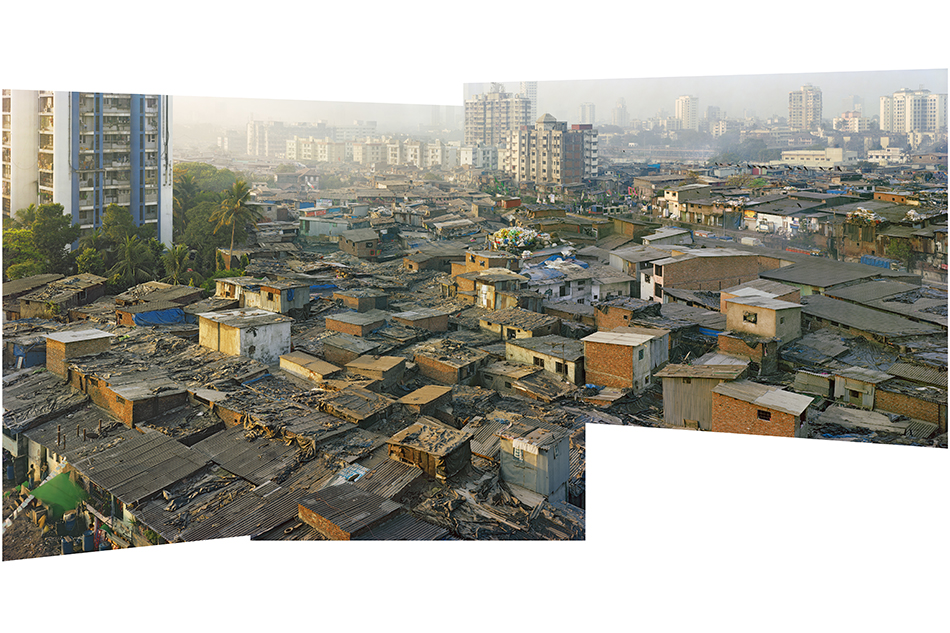

September 19, 2016Robert Polidori has captured both luxury and wreckage in his photographs. His new show at Paul Kasmin Gallery in Manhattan features images of the ruins of a once-glamorous hotel in Beirut and of Mumbai neighborhoods (portrait by Peter Keyser). Top: Hotel Petra #7, Beirut, Lebanon, 2010. All photos by Robert Polidori, unless otherwise noted

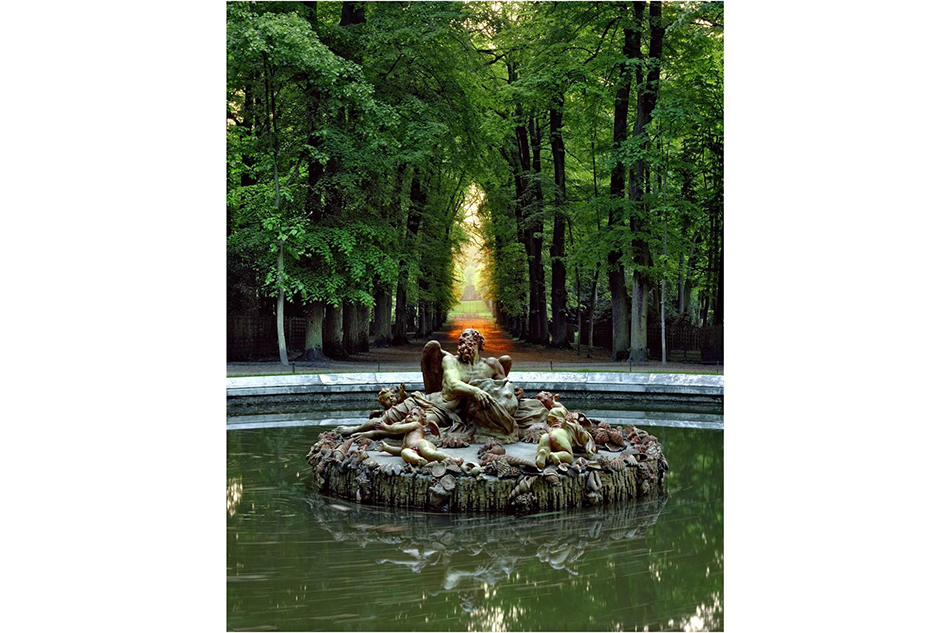

Throughout his career, the Montreal-born photographer Robert Polidori has been known for creating resonant images of empty, often decrepit rooms that still seem to pulse with the life of the people and events who have just passed through them. He has photographed an abandoned control room in Chernobyl, snipers’ lairs in Beirut, the picturesquely decaying Havana home of an erstwhile plutocrat and the restoration and continued maintenance of the palace of Versailles.

“The pictures succeed because, in part, Polidori eschewed nostalgia for something far more complex — the poignancy of absence,” Jeff L. Rosenheim, curator of photography at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, wrote in an essay about the photographer’s images of the wreckage left in New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina, which the museum exhibited in 2006. (Rosenheim’s words come from an essay in Polidori’s book After the Flood, published that same year by Steidl.) Like most of Polidori’s work, these pictures were taken with a large-format camera using only natural light. As Rosenheim observes, “One source of our lasting attraction to these merciless domestic landscapes is the certain knowledge that they will soon be gone forever.”

Polidori’s first show at New York’s Paul Kasmin Gallery (running through October 15) reveals a somewhat different side of his work. It includes seven images from his 2010 “Hotel Petra” series, shot in the once-glamorous Beirut property, which was badly damaged in the 1975–90 civil war and left to decay for 20 years. In contrast to the rooms and houses depicted in Polidori’s previous work, these ruins are often photographed in such extreme close-up that his pictures suggest richly hued oil abstractions.

The photos of Hotel Petra include abstracted close-ups like Hotel Petra Wall Detail #1, Beirut, Lebanon, 2010, which captures the peeling paint and other signs of decay from the building’s decades of abandonment.

The show is also the U.S. debut of Polidori’s photographs of so-called “dendritic” cities — those whose neighborhoods have developed organically, built by their inhabitants — represented here by Mumbai. These images, made between 2008 and ’11, capture entire neighborhoods using a technique that involves stitching together 8-by-10 and 11-by-14-inch photographs, each filled with houses and people, to form a single panoramic view. For example, 60 Feet Road, a tour de force named for a two-mile-long street of which Polidori shows a single block, is composed of 22 seamlessly connected images. Walking along the 40-foot length of the piece produces the odd sensation that you’re strolling down the street itself, peering straight into the lives of its residents.

With this exhibition, Polidori has returned to a contemporary art gallery. “Robert is using some very pioneering techniques and procedures,” says Mariska Nietzman, a director at Kasmin, “and he wanted the work to be seen beyond the confines of a photography gallery.” Polidori’s pictures tread the boundary between fine art and documentary photography, with the dendritic pictures — now printed on canvas — suggesting paintings and the pigment print “Hotel Petra” series reminiscent of gouache or pastel.

Polidori, who is 65 and lives in Ojai, California, shared his recollections of his career with Introspective during a recent visit to New York before the show opened. Here are edited excerpts:

Amrut Nagar #3, Mumbai, India, 2011, is another example of a panorama created by piecing together multiple images comprising a scene.

Polidori began by speaking of his beginnings as a filmmaker. A native of Canada, he studied at the State University of New York, Buffalo, in the 1970s, when the school was known for its avant-garde filmmaking program. In the 1980s, he worked as an assistant to Jonas Mekas at Anthology Film Archives, in New York City, before becoming a still photographer.

“People always ask, ‘How did you get into photography?’ Through Frances Yates, and her book The Art of Memory, which had a profound impact on me. It traces the history of mnemonic systems, from ancient Greece to the early seventeenth century. I had always thought the natural application of the camera was to serve history — that was its utilitarian function. But one of the things mentioned in The Art of Memory was that students of memory would study empty rooms, a concept the Romans called locus. In the cinema, whenever you saw rooms, the camera jittered and seemed nervous. Whereas in photographs, it was at repose. I followed that.”

Polidori then recalled the first rooms he photographed, in the mid-1980s: three Lower East Side apartments whose residents had died within two weeks of each other.

The damage sustained by the hotel during Beirut’s 1975–90 civil war and its neglect in the years since are readily apparent in Hotel Petra #6, Beirut, Lebanon, 2010.

“When I take photographs of empty rooms, they’re actually portraits of their inhabitants. What I’m capturing with Versailles is more of what I’d call a “collective superego” thing, like putting makeup on yourself. I also want to extract a structure from the subject itself. Where did I get that idea? Structural filmmaking. My favorite artist is Michael Snow, and my favorite film is Wavelength.”

That 1967 work, a classic of experimental cinema, spends nearly 45 minutes documenting the passage of time in a single room before zooming in on a photograph on the wall that depicts waves in the ocean.

Polidori said that he happened upon his first dendritic city in 1996. It was an extension of Amman, Jordan, built on a hillside and full of new structures but with no real roads, which he learned had been developed by Palestinians expelled from Kuwait during the first Gulf War. Although he realized fairly quickly that such cities exist worldwide, from Rio de Janeiro to Mumbai, he spent nearly 10 years perfecting the technique and tools for photographing and printing the images.

“It took me a long time to figure out how to make this work, because from the computer-stitching point, it’s complicated. But it forced itself into my consciousness. The resulting pictures are like the smallest cinematic tracking shots. Why do I do it this way? Because I don’t see the advantage of going against the laws of perspective and the Renaissance, just like I don’t see the advantage of going against conventional grammar. My work has gone from interiors to exteriors and the collective process of habitat.

“I didn’t do these pictures to glorify these people’s poverty. It’s true these people are poor, but I find them highly creative. Auto-constructed cities are cities that are built by their own inhabitants. In my work, I’m looking at organic nesting phenomena and human ingenuity.”