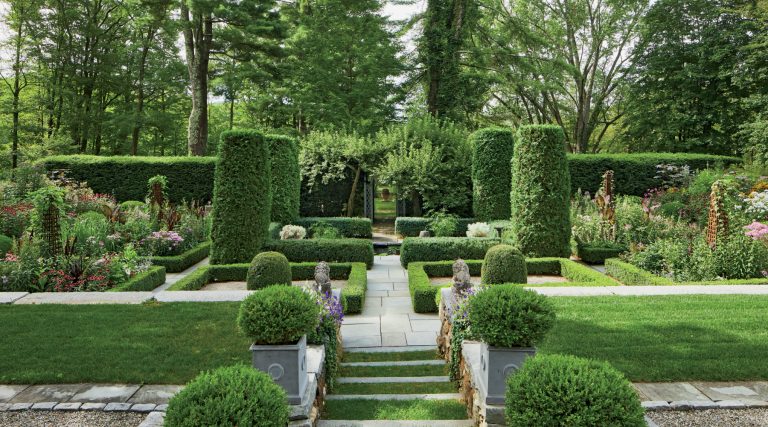

May 22, 2017A new book on the Rockefeller family gardens depicts contrasting Asian and Italianate influences. At Kykuit, overlooking the Hudson River, Bather Putting Up Her Hair by Aristide Maillol is framed by conical hedges and silhouetted against the morning light. Top: Lush flowers hide a flagstone lane leading through the moon gate at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden in Maine. All photos by Larry Lederman

We may not care to admit it, but the gardens of the rich and famous hold a special allure for most of us. Now, thanks to photographer Larry Lederman’s discerning eye, we get a whole-book look at two gardens belonging to the Rockefeller family — both designed in the early 20th century and both of great historical interest.

The first Eden featured in The Rockefeller Family Gardens: An American Legacy (Monacelli Press) is Kykuit, the clan’s country estate in Pocantico Hills, New York, 30-odd miles north of Manhattan. In the 1890s, John D. Rockefeller began buying land there high above the Hudson River, wanting an escape from the rigors of city life. After amassing more than 3,000 acres, he built what he considered an unpretentious stone house on the grounds and then entrusted his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., to oversee the creation of the garden, which is anything but simple.

Classical Italianate gardens were much in vogue at the turn of the century, and Kykuit, with its breathtaking views of the river, embodies this aesthetic. It was designed between 1906 and 1913 by architect William Welles Bosworth, who later created the Untermyer Garden in Yonkers, currently being restored. For Kykuit, he pulled out every weapon in his arsenal. There are replicas of fountains from Florence’s Boboli Gardens, wellheads from Venice, a temple, a grotto, a pergola fitted with a mushroom-shaped cast-stone table and stools, a monumental staircase, an orangery, pavilions, pleached allées of lindens and maples, imposing wrought-iron gates and a great many stone terraces, all recorded in vivid detail by Lederman’s camera.

The flaming-red leaves of Japanese maples brighten a shady stone path winding through Kykuit.

Of particular interest is the Japanese garden. At that time, anything Japanese was very much in vogue, and Bosworth made this a showcase of waterfalls, lakes, bridges and even a teahouse. Kykuit is planted with azaleas, peonies, irises, chrysanthemums, wisterias and lilies — all Japanese plants that were newly available in Europe and America.

When John D. Rockefeller Jr. died in 1960, his second son, Nelson, inherited Kykuit. Wanting to make the Japanese garden more authentic, he brought in landscape architect David Engel, who had studied in Kyoto under garden master Tansai Sano. Engel created a stroll garden and a meditation garden, while Japanese architect Junzo Yoshimura remade the teahouse.

Lederman’s many images of trees and rocks reveal the garden’s sense of mystery and adventure. Nelson Rockefeller’s real passion, however, was art, and over the years he made Kykuit the outdoor setting for his superb collection of 20th-century sculpture. Lederman shows how amazingly well the symmetrical lines of the formal and stylized garden work as a backdrop for the sculpture, which includes magnificent works by Picasso, Maillol, Calder and David Smith. Lederman’s photographs of these pieces in different seasons, are, for me, the most exciting images in the book.

The other garden featured is the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden, on Mount Desert Island, Maine. Created in 1926 by the noted landscape designer Beatrix Farrand, it is named for the wife of John D. Rockefeller Jr., the forward-thinking philanthropist credited with being the driving force behind the creation of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Farrand was much influenced by her clients’ strong interest in Asia and their wish that the garden house their growing collection of Asian sculpture.

A pair of ancient Korean granite animals and verdant ostrich ferns flank the flagstone path leading through the moon gate to the garden beyond.

This garden is unlike any of Farrand’s other designs in that it mixes Asian and European garden styles. Lederman captures the luminosity of the woods surrounding a moss-lined walk that goes from the main entrance to the Spirit Path, a gravel lane flanked by six Korean tomb figures. His camera also takes us down a flagstone path leading to the moon gate, which opens through an undulating pink stucco wall topped with Chinese tiles.

This wall encloses a vast and extravagantly colorful flower garden set around a huge rectangular lawn. Lederman shows us the dramatic contrast between the exterior Asian-styled meditative green garden and the interior plot planted with ebullient blooms in the manner of Gertrude Jekyll.

A noted Manhattan attorney married to the interior designer Kitty Hawks, Lederman pivoted toward photography 15 years ago when he realized he found trees and landscapes more compelling than his law practice. Prior to the Rockefeller project, he authored a book on the New York Botanical Garden and contributed to two others. Lederman’s interest in this particular subject was sparked by black-and-white photographs of the garden on Mount Desert that he chanced upon in 2011. His enchantment with them led first to a visit to Maine, then to Kykuit, and finally to the idea of doing a book, which was four years in the making. We should be grateful for Lederman’s patience: It means we can now experience each garden in its full glory.

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

(or support your local bookstore)