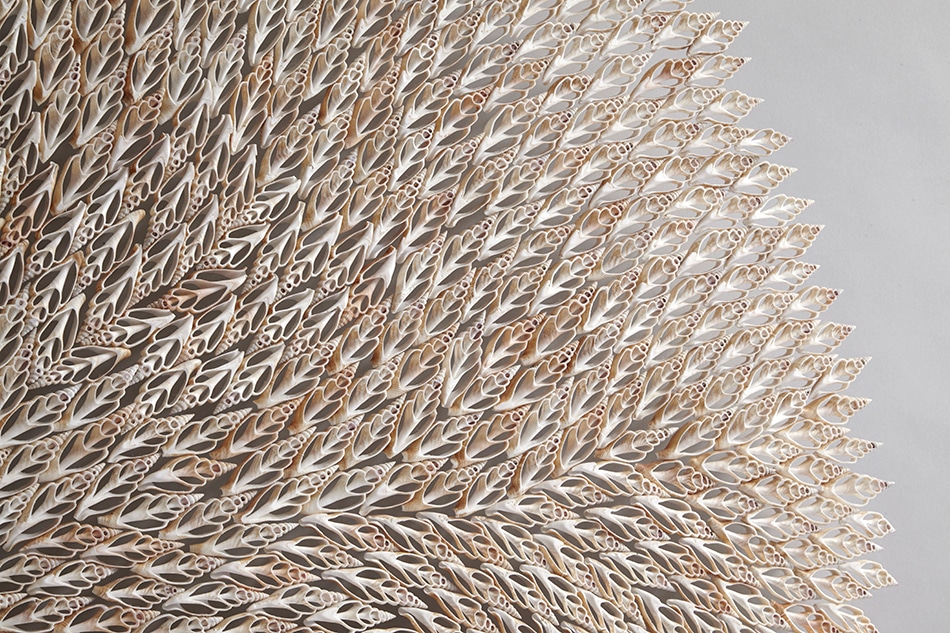

June 12, 2017“Praeteritum, Praesens et Futurum,” Rowan Mersh’s show at London’s Gallery Fumi, is his first solo exhibition. Last year, the artist’s sculptural shell screen Asabikeshiinh (Dreamcatcher), 2016, drew acclaim at the Pavilion of Art and Design. Top: Detail of Placuna Pro Dilectione Mea, 2016, on view at Fumi (Photo by Frankie Pike). All photos courtesy Gallery FUMI

For many visitors to the Pavilion of Art and Design (PAD) in London last fall, there was one absolutely standout piece: the Asabikeshiinh screen, made entirely of sliced Turritella shells by British sculptor Rowan Mersh, which cast fantastic shadows over the walls and floor of Gallery Fumi’s stand. Probably the most Instagrammed work of the fair, it was honored with the Best Contemporary Design award.

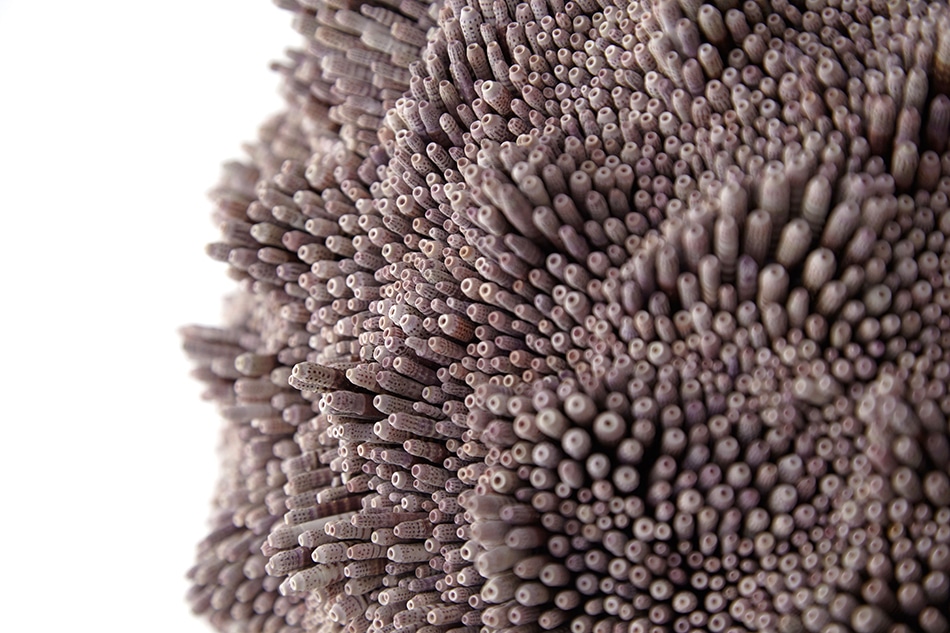

Through July 1, London’s Fumi gallery is presenting “Praeteritum, Praesens et Futurum” (Latin for past, present and future), Mersh’s first-ever solo show, which prominently features Asabikeshiinh II alongside a collection of new pieces and several produced over the past five years. Among the former are wall sculptures made of tiger-sea-urchin spines and one of sliced strombus vittatus, a species of sea snail. Also on display are pieces — some wall mounted and others freestanding — constructed of dentalium, Placuna (windowpane oyster) and Turritella shells, including a six-foot-tall three-dimensional sculpture made in collaboration with Bob Lorimer, another Fumi artist.

Mersh studied mixed-media textiles at Loughborough University School of Art and Design and later at London’s Royal College of Art, from which he graduated in 2005. Since then, his practice has evolved from textile sculptures and kinetic installations to functional objects (tables and chandeliers, for instance, previously shown at Fumi) to large-scale wall pieces and freestanding sculptures. From 2012 on, he has focused almost exclusively on sculptural pieces made of responsibly sourced shells, which despite their material, appear soft and fluid.

Take the “Asabikeshiinh” screens. The name translates as “dreamcatcher,” but the term derives from the Native American Ojibwa word for spider. “The dreamcatcher is widely believed to have derived from an ancient legend within Ojibwa culture,” Mersh explains from his studio in East London. “Elders speak of the Spider Woman, known as Asibikaashi, who watched over the children of the land. As the Ojibwa nation spread to all corners of North America, it became difficult for her to reach every child. So, Asibikaashi directed mothers and grandmothers to weave magical webs for the people from various sacred natural materials. These ‘dreamcatchers’ would filter out all bad dreams and allow only good thoughts to enter their minds. Once the sun rose, all the bad dreams just disappeared.”

“Shell by shell, the works organically evolve, as might a collection of self-informed brushstrokes.”

Asabikeshiinh II (Dreamcatcher II), 2017. Photo by Frankie Pike

To create the “Asabikeshiinh” pieces, Mersh first sliced the cone-shaped shells, then ground, shaped and polished the pieces by hand to reveal their lace-like central cavities. Next, he bound them together with fluorocarbon resin, which doesn’t discolor over time. Each placed shell informed the shape, size and position of the next. It took many months for Mersh to assemble the 5,000 cut shells that compose the original work, assisted only by his friend the sculptor Nathan Pass. For the smaller, round Asabikeshiinh II, Mersh used more than 3,000 shells.

“The challenge was to create a near-perfect two-dimensional geometric shape that gives the optical illusion of a three-dimensional form,” he says. “That meant working from the center outwards, using progressively smaller shells towards the edge of the piece, an idea that was touched upon but not fully realized through the first Asabikeshiinh.”

Working with shells fascinates him. “As layers of the shells build up, their curvature informs the three-dimensional aspect of the form,” he explains. “As one form is completed, the next is born. Shell by shell, the works organically evolve, as might a collection of self-informed brushstrokes.”

Mersh also cites historical, social and contextual reasons for working with specific types of shells. “Dentalium shells [used to create his “Pithváva” series of wall sculptures] have been considered a highly valued trade item by First Nations and Native Americans for thousands of years,” he says. “The oral history of the Yurok, an indigenous Californian tribe, refers to Pithváva, a deity who created dentalium shells and told of their significance as sacred wealth. This installation explores the notion of sacred wealth as an art form through a contemporary, artisanal method of creation.”

Valerio Capo and Sam Pratt, directors of Gallery Fumi, first worked with Mersh when he created an installation for their “Corn Craft” exhibition in 2009.

Mersh’s artworks, which are in the permanent collections of the V&A and the Jerwood Gallery of modern and contemporary British art, among other institutions, echo as well the patterns created by nature — the disturbed nap of animal fur, say, or the tentacles of sea anemones. For him, the natural world is a never-ending source of inspiration and wonder. “I hope that the beauty and fragility of nature is reflected in my work,” he says. “What I strive to do is celebrate the inherent beauty of the material itself.”

Gallery Fumi has been working with Mersh since its 2009 “Corn Craft” exhibition. “After the economic crisis, we wanted to invite people to reconsider the notion of beauty, appreciating humble and inexpensive materials,” says Valerio Capo, the gallery’s co-founder with Sam Pratt. “We picked corn as the material our designers and artists had to work with, and Rowan made a beautiful ceiling hung with corn fans. It was an amazing installation.”

This is a big year for Fumi, which recently moved from Hoxton Square, in East London, to a new showroom in Mayfair. “We are very excited about the location because it is very spacious and is on two floors,” says Capo. “Our designers are currently making new works that will fit perfectly within this space.”

That they have chosen Mersh for the new site’s inaugural exhibition is indeed a compliment to the artist, but as PAD proved, he creates show-stopping work. “Rowan’s designs are magical, elegant and surprising,” says Capo. “He is fantastic with his hands, and he manages to make any material, even the hardest, look soft and dynamic.”