December 1, 2024When Everette Taylor bounds into the Lehmann Maupin gallery in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood on a sunny Friday afternoon, it is evident that he’s got the art collecting bug. He’s hungry for information and open to inspiration.

The 35-year-old Taylor, the CEO of Kickstarter and a recent addition to the board of 1stDibs, is a fashionable sort, dressed in an all-black outfit composed of a suit from the Japanese brand Sillage, a Maison Margiela shirt and chunky Bottega Veneta shoes. “If you catch me at a gallery, I’m wearing something airy and comfy,” he says before embarking on an afternoon during which he’ll stop at three 1stDibs galleries, including Yossi Milo and Yancey Richardson.

At Lehmann Maupin, he’s immediately wowed by the show of pioneering Korean artist Sung Neung Kyung, particularly a row of five collages on newspaper that are mounted not flat against the wall but attached to it by one edge, so that they protrude into the gallery space.

Taylor appreciates Sung’s mixed-media pieces with pointed political messages. But frankly, it is the installation that intrigues him most, planting a seed. “These are so cool!” he says.

The reason for his enthusiasm is that even though he has been collecting only since 2017, he is already running out of wall space in his townhouse in the Bed-Stuy neighborhood of Brooklyn, and he thinks he could fit more art there if he tried this arrangement. (He has already suspended paintings from the ceiling.)

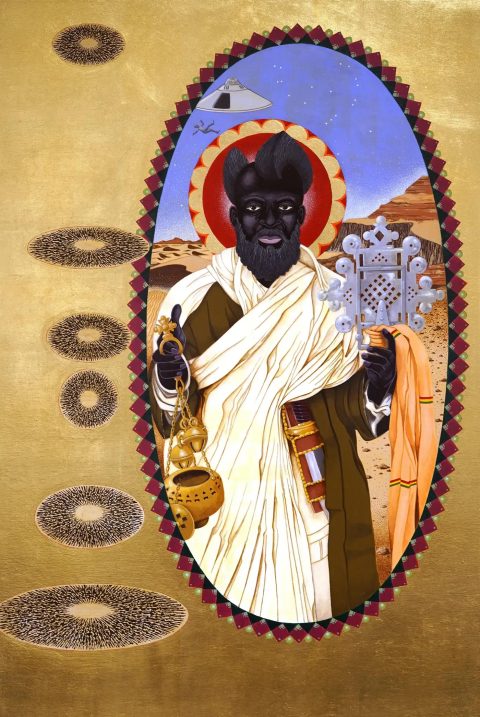

Taylor began his collecting with Black artists, mostly paintings and frequently figurative scenes, ramping up his acquisitions while he was in his previous job, as chief marketing officer of Artsy. “I saw myself in those works,” he says. He owns pieces by superstars like Derrick Adams, Sam Gilliam and Mickalene Thomas, as well as Lehmann Maupin artists like Dominic Chambers.

Lately, he’s begun to expand his horizons. Hence his Chelsea excursion. “I started out wanting to buy only Black artists, but now I’ll buy anything as long as I love it,” he says. “I don’t want to put myself in a box.”

On Lehmann Maupin’s second-floor, gallery partner Fionna Flaherty shows Taylor a work by another artist: Kim Yun Shin’s Add Two Add One, Divide Two Divide One 1987-No. 86, 1987–88, a totemic wood sculpture carved with a chainsaw.

“I’ve wanted to collect more ceramics and sculptures,” Taylor says, lifting his sunglasses to examine the piece more closely. Flaherty tells him about the artist’s travels outside her native Korea to places like Argentina and how she’s been inspired by many cultures.

Asked which of the gallery’s works he would take home today if he had to pick, Taylor chooses this one. “It’s unique,” he says. “You could look at it a million times and see something new — and I save on wall space.”

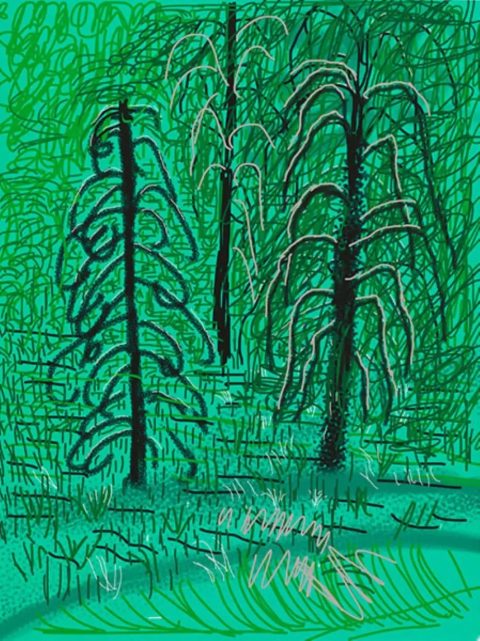

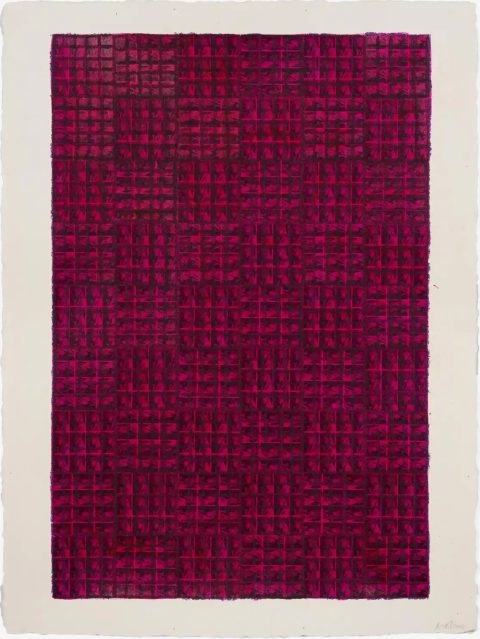

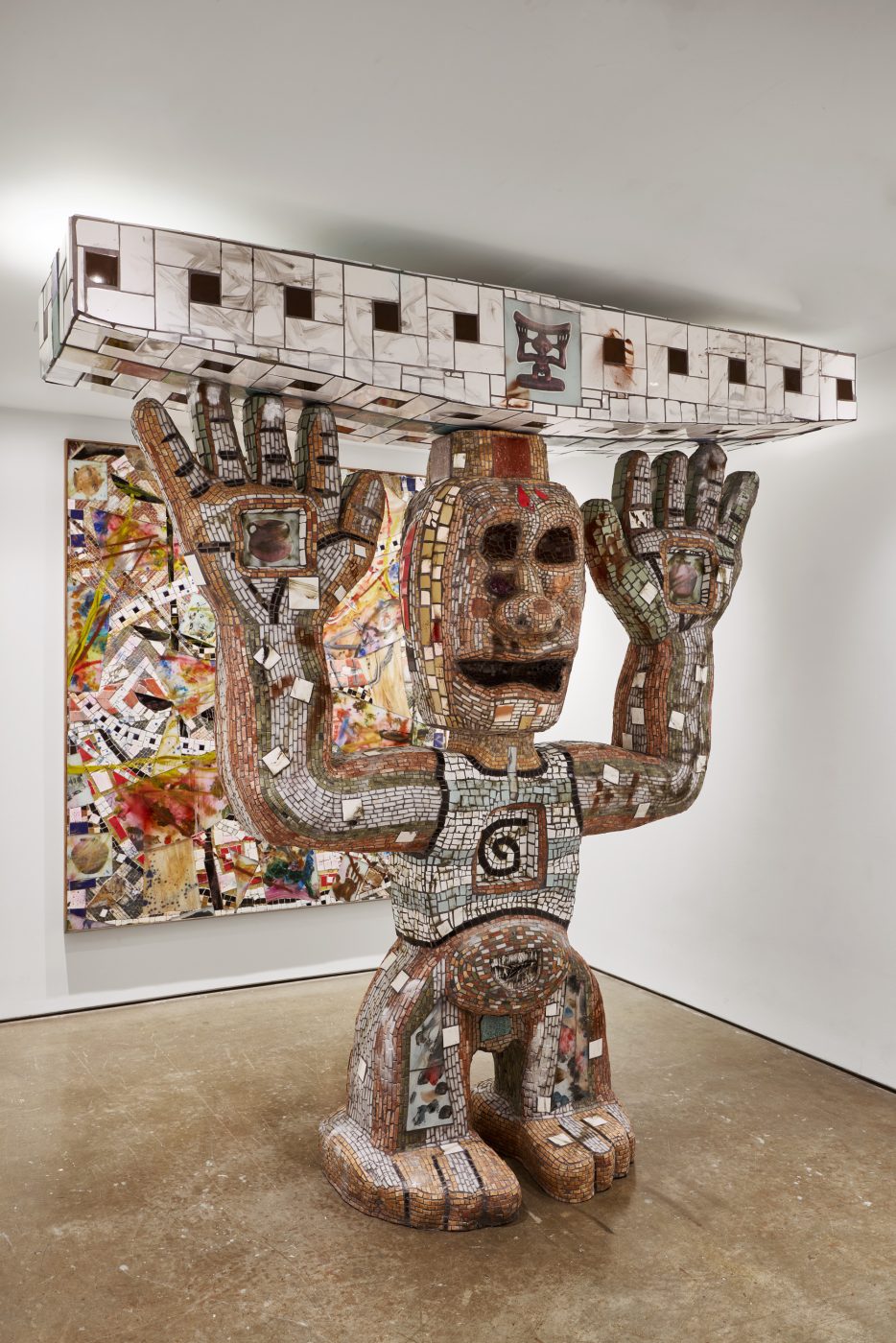

With that, Taylor is off to Yossi Milo Gallery, just a few steps away, to view a show titled “Labyrinth,” featuring the Brooklyn-based artist Cameron Welch. Welch is on hand, as is Milo. Taylor is eager to engage with the former, who works primarily in mosaic these days.

“I talk to artists all the time, and they each have their own visual language,” says Taylor. “Cameron’s visual language is so distinct.”

“Labyrinth” contains a couple of sculptures, but most of the pieces on display are wall works made with marble, glass, ceramic, stone and oil. Welch’s compositions are complex and jam-packed, with some recognizable figures (like a minotaur) emerging out of a chaotic abstract swirl.

Taylor tells Welch his favorite work is the squarish Labyrinth “Walking the Maze” III, 2024, among the most abstract of the pieces. “I love the moments in this one, and I like the painterly aspect of it — the reverse painted glass in it really shows what he can do,” Taylor says.

Welch is flattered, saying that the technique is a recent adoption. “I really appreciate it,” he says. “It’s new for me.” When Taylor is asked if he already owns one of Welch’s works, his reply is a hopeful “Not yet!”

Taylor’s willingness to take a flier on something new was already evident in his first, improbable collecting foray, in 2017: He bought a raffle ticket at a charity event and won a painting, Red Whisperer, by Jon Hen.

Taylor was living in Los Angeles at the time. “I brought it back to my apartment, and it transformed everything,” he recalls. “You see things differently once you put a piece of art in your home.”

From there, he was off on what he calls a “self-taught” collecting journey, educating himself on Instagram in the beginning and eventually graduating to the big leagues when it came to actually buying. “1stDibs gives me a marketplace I’m using constantly,” says Taylor. “The advantage of it is the ability to filter by size, color, price and so on.”

Online tools are incredibly useful, but one of Taylor’s tips is to also talk to art dealers in person about the work they represent. “Galleries want you to ask questions,” he says. “Engage and learn.” That takes time, of course — if you do it right, “it could be a full-time job,” he says. That’s one of the reasons why he says he thinks “collecting is a privilege.”

He also urges budding collectors not to fall for hype. “I won’t sacrifice just to buy a name,” he says. “It’s about the piece itself.” Another bit of advice: “Don’t forget that you can put art in your bathroom. Don’t let anyone tell you that’s a bad thing.”

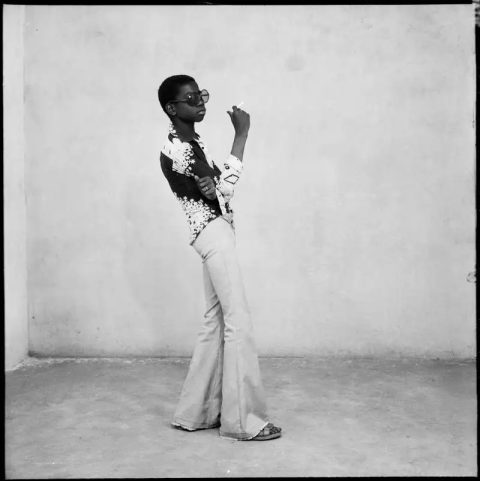

With that, he arrives at his last stop of the day, the photography specialist Yancey Richardson. “I haven’t collected tons of photography, but I want to,” Taylor says.

A work by the South African photographer Zanele Muholi — known for her high-contrast, saturated black-and-white images — steals his heart right away: “Zibandlela, The Sails, Durban,” 2020, a triptych composed of three self-portraits, each of which has a doubled image.

“It’s her shooting into a mirror,” says Richardson, noting that one version of the picture is in the Phillips Collection. “She shoots digitally, and it’s a stripped-down process, nothing fancy. The towel on her head is just a hotel towel.”

Standing in front of the Muholi, Taylor says, “It’s not only the work but the presentation as a triptych — she’s one of the best at what she does. I can see this in my home.”

On the adjacent wall is a photograph by someone Taylor knows personally: Mickalene Thomas’s Kindred Spirits, Tamika and Qusuquzah Sitting on Couch, 2022, portraying two Black women dressed glamorously in one of Thomas’s constructed interiors.

Taylor grew up in a housing project in Richmond, Virginia, and he had only a high-school degree before starting his first business, an event-marketing software company, which he sold for a considerable sum at age 21. “These striking images of Black women, powerful and stylish, remind me that I wouldn’t be where I am today without those women,” he says. “The attitude is, ‘We’ll be fly by any means necessary.’ ”

Thomas, he adds, “is putting something positive into the world. These women could be my aunts or cousins.”

That emotional bond is what drives Taylor’s acquisitions, regardless of the medium. “Be sure you have a deep connection to the work,” he advises collectors. “You have to make hard choices with art. It has to resonate.”