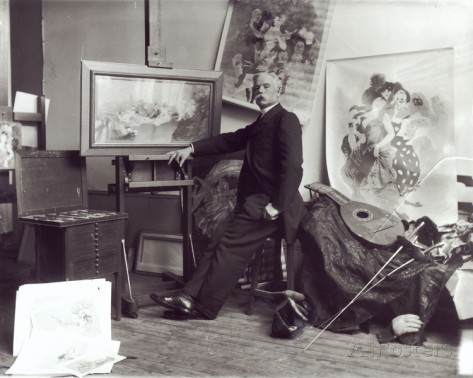

July 10, 2022Once upon a belle époque, Jules Chéret (1836–1932) was the toast of Paris. Today, this extraordinary artist and printer is little known. Which is at once surprising and somehow fitting, since what earned him great acclaim, including the Legion of Honor, was itself ephemeral.

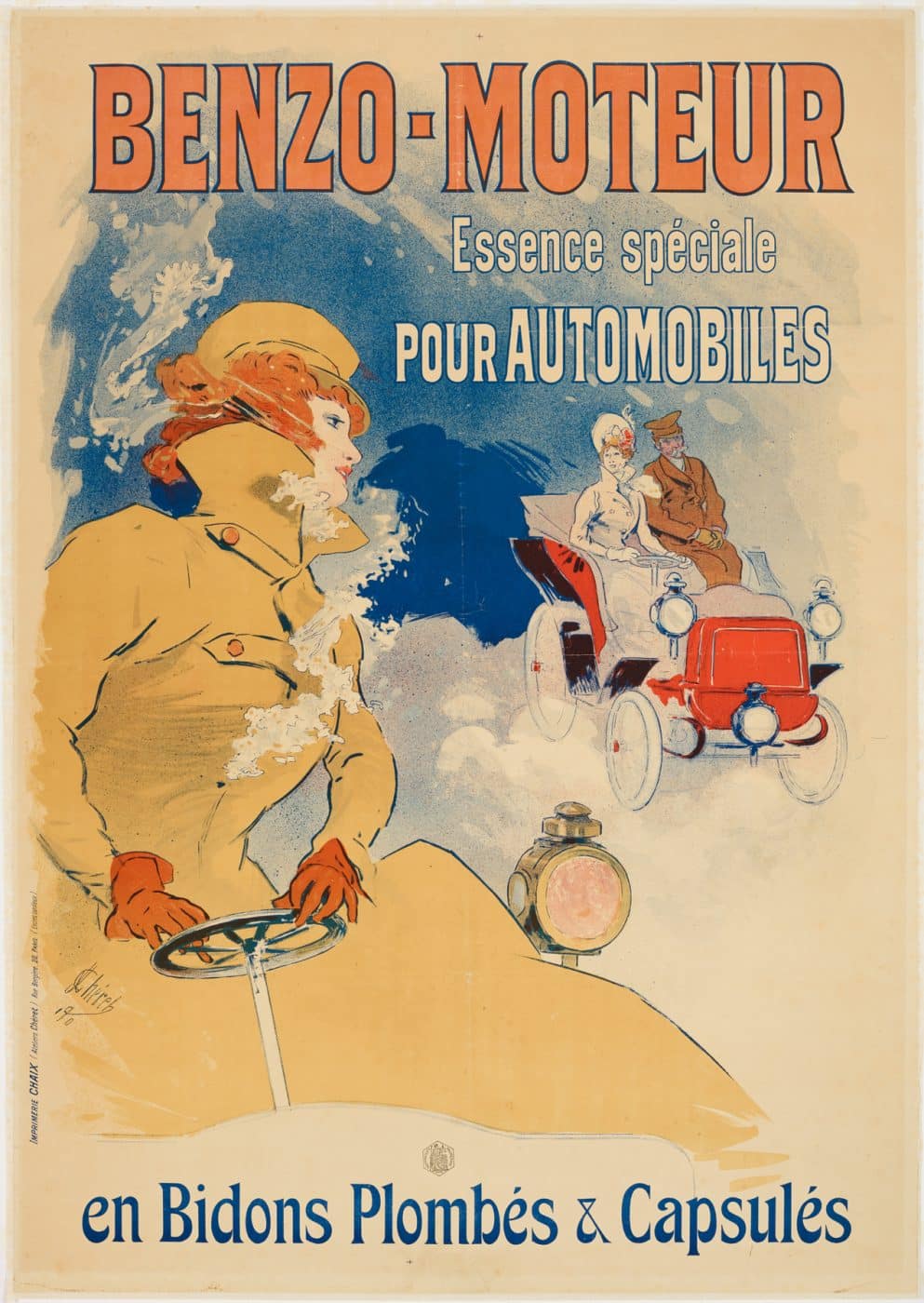

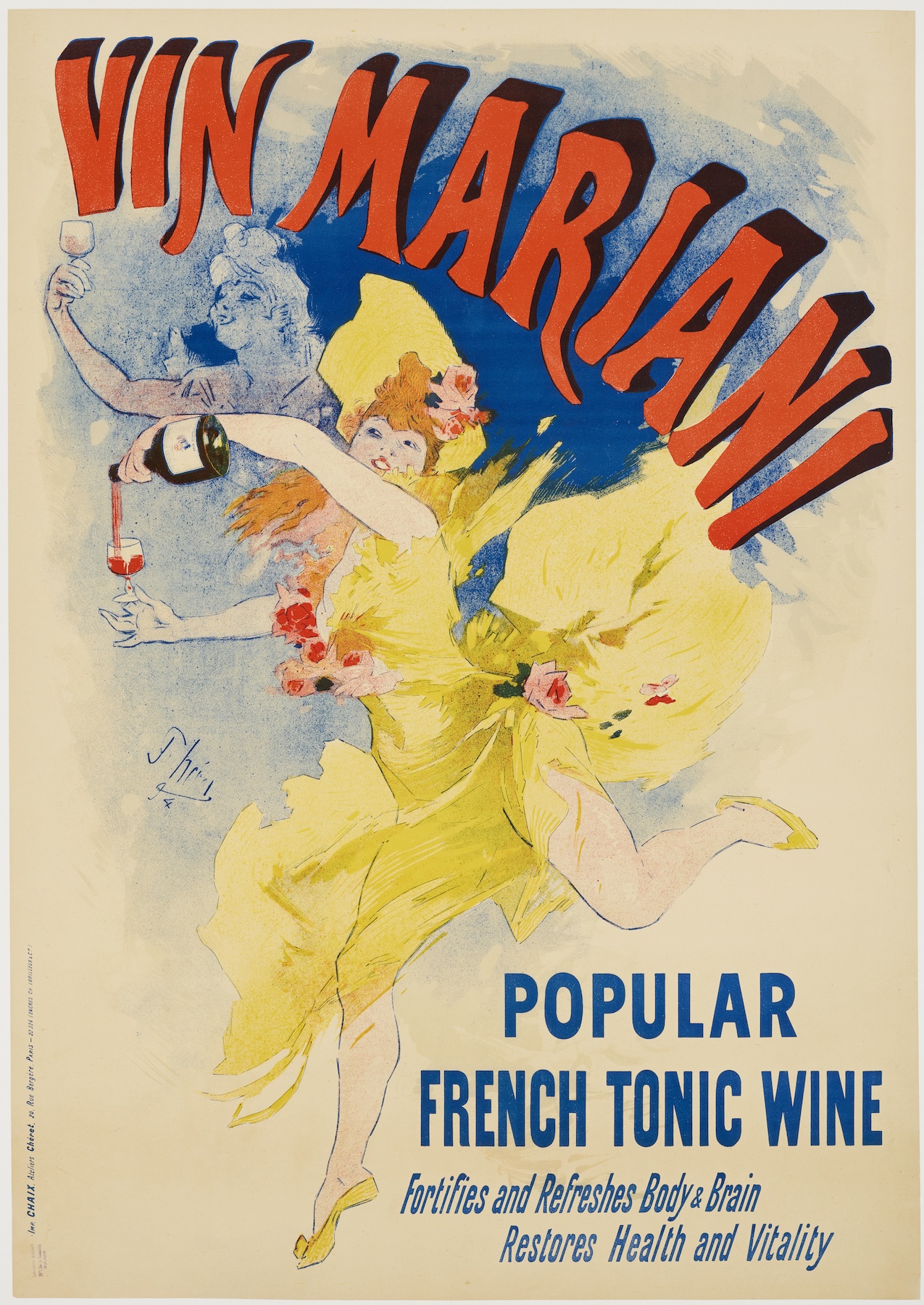

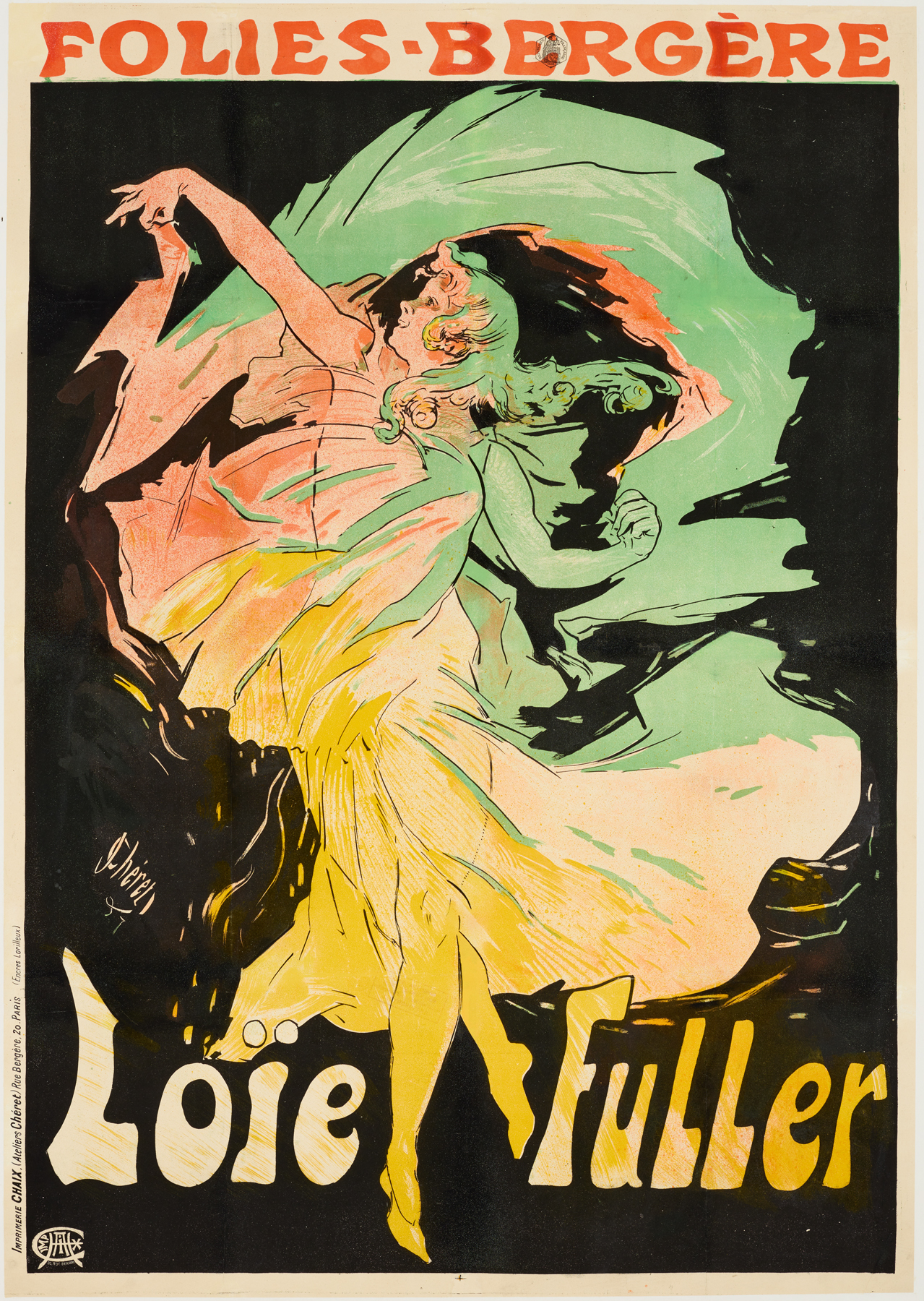

It was Chéret who transformed the street advert into the most expressive and coveted art form of the late 1800s. Think: a red-headed belle in a flimsy yellow dress, frolicking through a field of blue as she pours a glass of “tonic wine,” with the brand name Vin Mariani wafting about her. Through his bold advances in chromolithography and the graphic arts, Chéret and the younger talents he inspired — like Pierre Bonnard, Alphonse Mucha and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec — along with other artists, turned the stone-gray streets of Paris into a kaleidoscopic, ever-changing urban spectacle.

With larger-than-life imagery, their poster advertisements for performers, music halls, theaters, department stores, aperitifs, bicycles and cigarettes were so gay and grand that Parisians from every walk of life felt compelled to “collect” them, whether by stripping them surreptitiously from the walls of buildings or buying “collectible” versions in print shops or from poster books. (One of the most famous such compendiums, Les Maîtres de l’Affiche, was published by Chéret himself.)

Fleeting in nature yet enduring in vision, the French fin-de-siècle poster embodied the new spirit of modernity that was then taking hold of Parisian society, a fresh openness to innovation and exploration. Never before had there been such a thirst for novelty, nor had it pervaded so many areas of life.

The poster was as much a document as a product of this rapid change, reflecting the emergence of consumer and celebrity cultures, as well as the travel industry, and a new independent young woman. That the poster should be embraced so ardently as art is also remarkable, considering that up until then, artistic works that made contemporary life their subject were largely disdained, as were those that were mass-produced. Which is why it is hard to imagine what the history of modern art — or, for that matter, commercial advertising — would have been without Jules Chéret and his placard.

The Milwaukee Art Museum’s exhibition “Always New: The Posters of Jules Chéret,” on view through October 16, promises to reclaim the “king of the poster” from obscurity. Comprising works drawn from the museum’s newly acquired James and Susee Wiechmann Collection of more than 600 posters, prints and drawings, assembled by the couple over 30 years, it is the first solo exhibition of his work in the United States. An accompanying 240-page, full-color catalogue, with essays by the exhibition curator, Nikki Otten, and other scholars, is nothing short of a revelation.

Raised in a family of poor Parisian artisans, Jules Chéret was apprenticed to a lithographer at 13. Although he took a class at the École nationale de dessin, as an artist, he was largely self-taught, schooling himself in art history and technique by visiting remarkable works at museums. When his first solo poster designs failed to garner further commissions, Chéret, then 23, relocated to London, where colorful but text-heavy posters enlivened the streets.

The move proved pivotal, as he soon found work with the French expat Eugène Rimmel, a visionary businessman and one of the founders of the beauty and healthcare industries. A brilliant marketer, he regularly produced colorful, elegantly illustrated and culturally sophisticated catalogues to publicize House of Rimmel cosmetics and fragrances. These and other promotional ventures kept Chéret busy, while sharpening his understanding of the commercial potential of print.

So, when he learned of the invention of a press that could print large-scale formats inexpensively, Chéret recognized an opportunity to become his own boss. Now 30 years old, he returned to Paris with the financial support of Rimmel to establish his own print shop specializing in jumbo-size street posters and set about forging a fresh, eye-catching approach to their design.

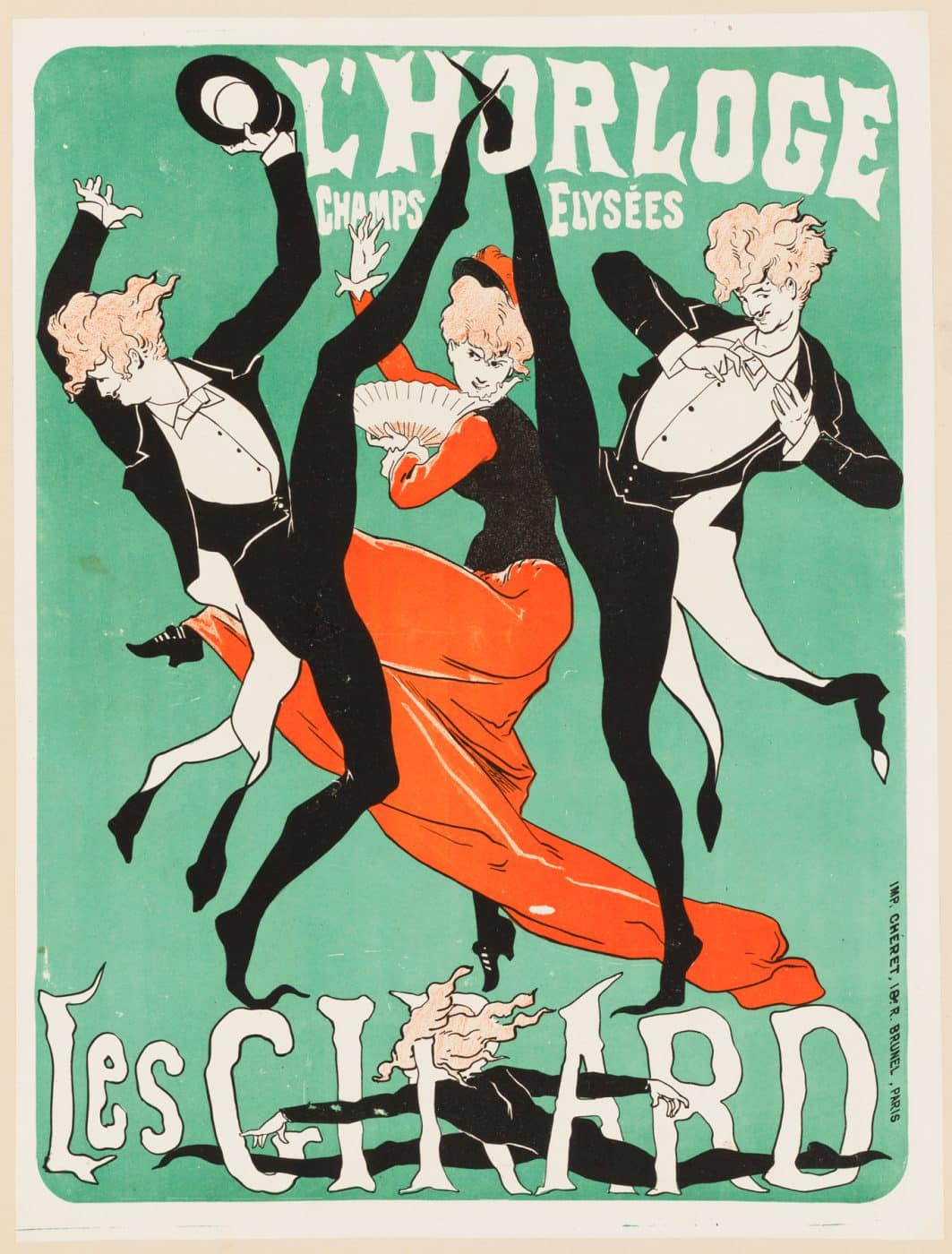

An 1868 poster for the Gaulois Revue at the Théâtre Déjazet showcases this emerging style. Colorful, amusing figures occupy the foreground, with sprightly vignettes surrounding them. There is little text, but what there is frames the image in an arresting manner. Over the next decade, Chéret’s compositions grew ever more dynamic and bolder, as demonstrated by his witty poster Folies-Bergère, Les Girards (1877), its text and imagery united in dance.

During this period, Chéret was also advancing chromolithography. The conventional process required drawing an image on a piece of limestone with a greasy crayon and then transferring it onto a sheet of paper using a hand press. The procedure had to be repeated with a different stone for each color in the print, which was extremely time-consuming.

Chéret accelerated the process by adding a stone with a graduated background that scaled in hue from orange to blue. With this, in addition to red- and black-pigmented stones, he could make vibrant posters more quickly and cheaply. In the late 1870s, his acquisition of steam-powered presses further sped up production and dramatically increased the volume of his output.

But perhaps Chéret’s greatest contribution to our world today was a simple insight into an eternal truth: Sex sells. The best way to market a product is to put a pretty, revealingly dressed young woman in the ad. In the 1890s, Chéret put so many to work in this cause that they came to be known as “Chérettes,” a conflation of chérie (“darling”) and Chéret. Descended from the enchanting mademoiselles in the bucolic painterly confections of Watteau and Fragonard, all smiles and femininity, they fused the present with the past, making them potent symbols of a newly affluent and peaceful France.

Back then, the growing proliferation of consumer goods was nothing short of a miracle; today, we regard it as the beginning of an environmental nightmare. Our attitude toward advertising has taken an equally dark turn. And yet, it’s impossible not to be charmed by the effervescent Chérettes or admire the genius and industry of the man who conceived them.