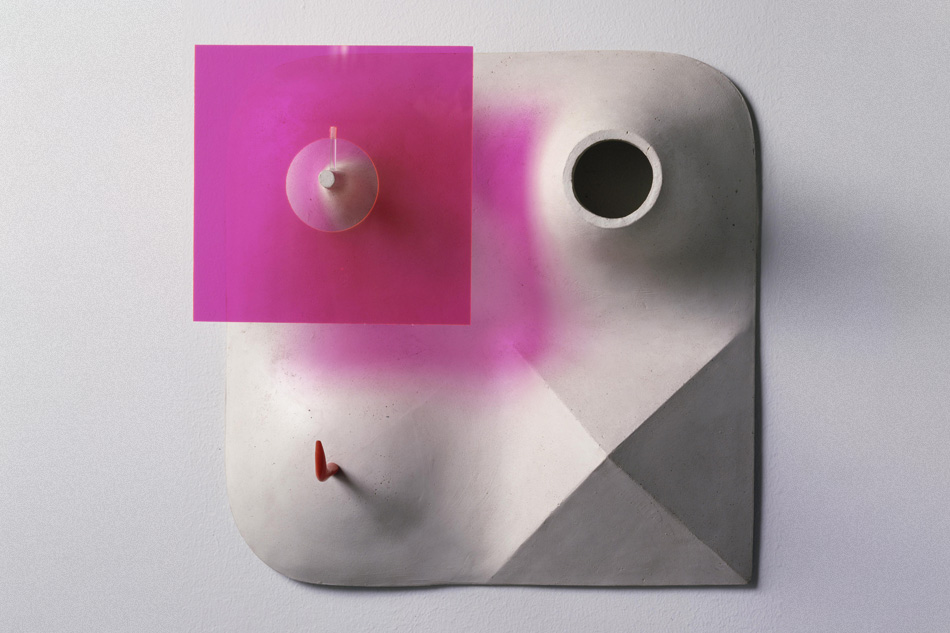

March 20, 2017A timely new show at the Noguchi Museum, in Long Island City, focuses on work that the Japanese-American artist and designer Isamu Noguchi made based on his 1942 stay at Poston, a Japanese internment camp set up by the U.S. government during World War II (portrait © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / ARS). Top: An installation view of the exhibition. Photo by Nicholas Knight

Design aficionados like to visit Long Island City’s Noguchi Museum, in the New York City borough of Queens, to see Isamu Noguchi’s massive hand-carved stone sculptures, delicate Akari paper lanterns and 1950s biomorphic — and now iconic — furniture designs. Housed in a once-industrial building near the artist and designer’s former studio, with an adjacent sculpture garden, the museum is the first in this country founded, designed and installed by a living artist focusing on his own work. It is like a sanctuary in the city.

A new exhibition there is far less celebratory, however. “Self-Interned, 1942: Noguchi in Poston War Relocation Center” (running through January 7, 2018) is a sobering show about the Japanese-American sculptor’s decision to voluntarily enter an internment camp during World War II. It includes two dozen works made before, during and after his stay, along with letters and an essay about the searing experience.

The exhibition is particularly timely, given the current political uproar about immigration and the U.S. president’s recent actions targeting certain ethnic groups, but it was not intended to be so.

“When we planned the show, eighteen months ago, we had no idea what November would bring, so it has extra resonance,” explains director Jenny Dixon.

“Noguchi left his estate to the museum, so once a year we do a thematic exhibition with things from the collection,” says senior curator Dakin Hart. “We planned this one to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of Executive Order 9066, the wartime directive that resulted in the internment of Japanese citizens and Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast.”

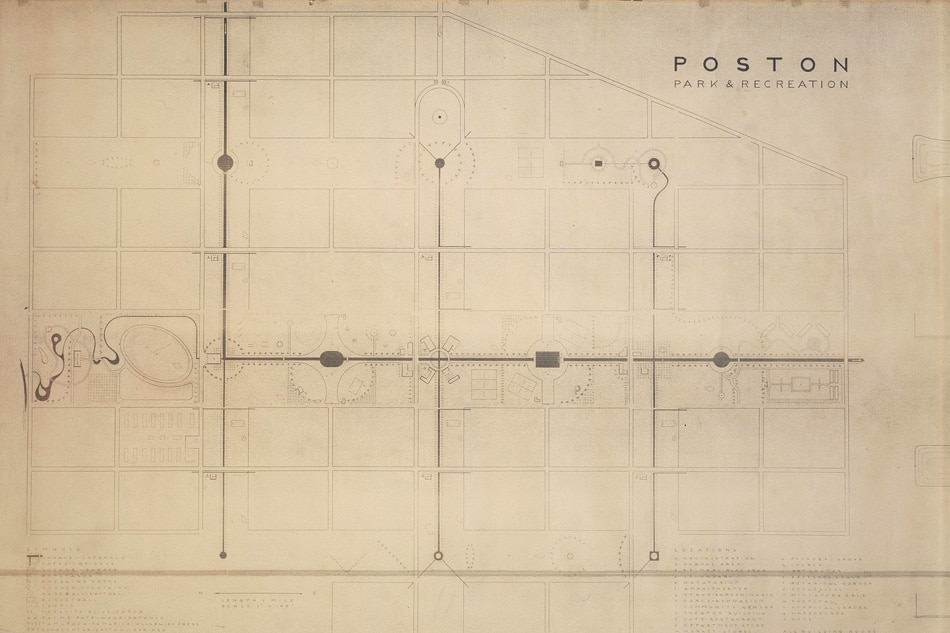

In 1942, Noguchi volunteered at the camp, located in southwestern Arizona, as an act of patriotism; because he was living on the East Coast he was not interned. He asked a friend at the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C., to pave the way for him to get a job. He wanted to make the camp a more hospitable place by planting vegetables, building baseball fields and teaching traditional ceramics and woodworking.

Some works included in the show, such as Mother and Child, 1944–47, have a more soothing sensibility than others. Photo by Kevin Noble

As Hayden Herrera makes clear in her 2015 biography, Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi, it all went terribly wrong. Looking like a concentration camp, Poston had hundreds of one-story, tar-paper-covered barracks. It was 120 degrees during the day and cold at night. Just 37 cents per person per day was allocated to feed the internees, and what was provided was so awful that most of them got sick. Noguchi could not obtain the tools, supplies or permission to teach his courses. Having gone there as an instructor, he thought he was different, but he soon found that he was treated like every other detainee.

“Suddenly I became aware of a color line I had never known before,” Herrera reports he once said. “Suddenly you become a member of a minority group.” When he tried to leave, he was forced to remain and had to lobby his influential friends in Washington in order to get out. He eventually succeeded, but it took him six months.

The show ignores Noguchi’s earlier career. By 1942, the artist was a darling of the art establishment: a popular, handsome social lion. He knew everyone. In Paris, back in the late 1920s, when he was on a Guggenheim fellowship, he had worked for Constantin Brancusi and was friendly with Alexander Calder, Man Ray, Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita, Stuart Davis and Ezra Pound. After returning to New York in 1929, he was given solo gallery shows that drew rave reviews. He sculpted portrait busts of acquaintances George Gershwin, Berenice Abbott, Martha Graham and Lincoln Kirstein. He hung out with Arshile Gorky, David Smith, Willem de Kooning and Buckminster Fuller. He was a man-about-town.

The show, titled “Self-Interned, 1942: Noguchi in Poston War Relocation Center,” will be on view through January 7 next year. Photo by Nicholas Knight

Given the plights of many immigrant and ethnic communities in the U.S. right now, Noguchi’s stainless-steel Doorway, 1964, feels particularly poignant. Photo by Kevin Noble

Noguchi was in Japan studying pottery making in 1931 when the Japanese invaded Manchuria. He caught what he called “the last boat” back to the States. In 1935, he traveled to Mexico, meeting Diego Rivera and falling in love with Frida Kahlo, who became a lifelong friend.

He returned to New York and, in 1938, won the design competition for a plaque about freedom of the press for the facade of the Associated Press Building in Rockefeller Center. (There were 188 entries from 26 states.) He wasn’t rich, but he was successful.

Noguchi was in California when Pearl Harbor was attacked, and he saw the growing racial hysteria against the Japanese. After President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 went into effect, in 1942, Noguchi went to Washington and petitioned for the job at Poston, the largest of the relocation camps. “The dust was blowing as I arrived in Poston,” Noguchi wrote in an unpublished essay commissioned by Reader’s Digest. “Eye-burning dust, and the temperature seemed to stand at 120 degrees for three solid months.”

The place was packed: “The new arrivals keep coming in,” he wrote. “Out of the teeming buses stumble men, women, children, the strong, the sick, the rich, the poor.”

Yet he was lonely. And so he began to make art. He picked up ironwood branches from the desert for sculptures. He completed a pink Georgia marble bust of Ginger Rogers (a prewar commission). He made assemblages of wood and bone.

Noguchi’s work grew more political after he left the camp, a fact apparent in several pieces included in the show: the wood sculpture Remembrance, the cast-bronze This Tortured Earth and the multimedia sculpture The World is a Foxhole, all completed within two years of his stay in Poston. Other works in the exhibition reflect his time there even though he made them decades later, most obviously a red Persian travertine sculpture of an Arizona mesa titled Double Red Mountain (1969) and a slash of galvanized steel set low to the ground titled Cactus Wind (1982–83). “The experience of the desert became an important part of his mental furniture,” Hart says.

Yet the artist remained philosophical and determined to fight prejudice. “To be hybrid anticipates the future,” he wrote in his essay. “This is America, the nation of all nationalities.”