February 13, 2017Included in the recently published Sunnylands (Vendome) is a February 1964 letter to architect A. Quincy Jones, in which Walter Annenberg wrote, “We might even have elements of cacti worked in on the golf course area.” Above, the view from Annenberg’s study. Top: Works by van Gogh and Gauguin hung around the living room fireplace, which was never lit. Photos by Mark Davidson, courtesy of the Vendome Press

Try to picture “Palm Springs modernism” and you’ll probably imagine a house that is modest but geometrically compelling. The building is set into a hillside, allowing its right angles and nature’s curves to interact. Sliding doors, kept open, merge indoors and out, multiplying the available living space. Furniture, like the building, is sleek. And the limited palette is captured perfectly in black and white.

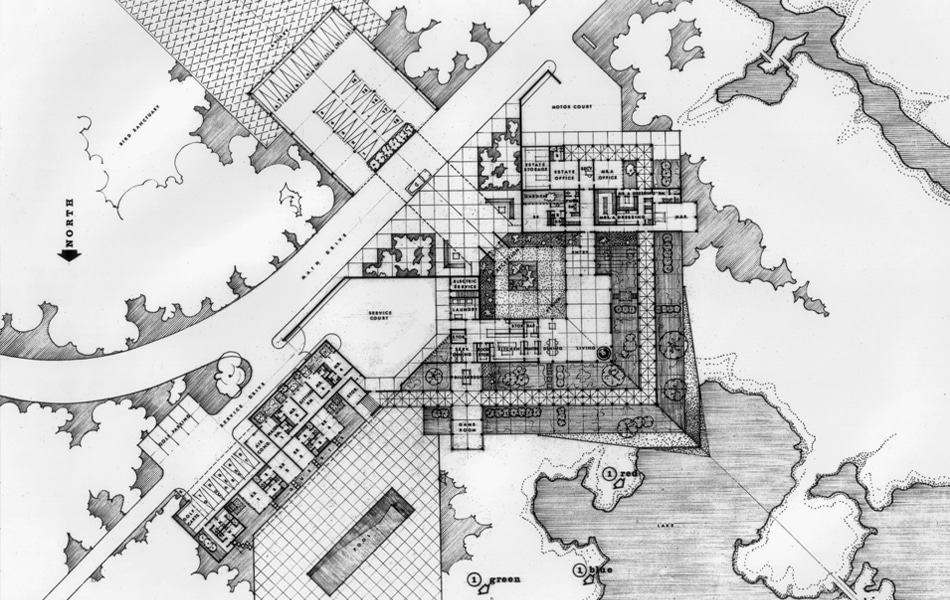

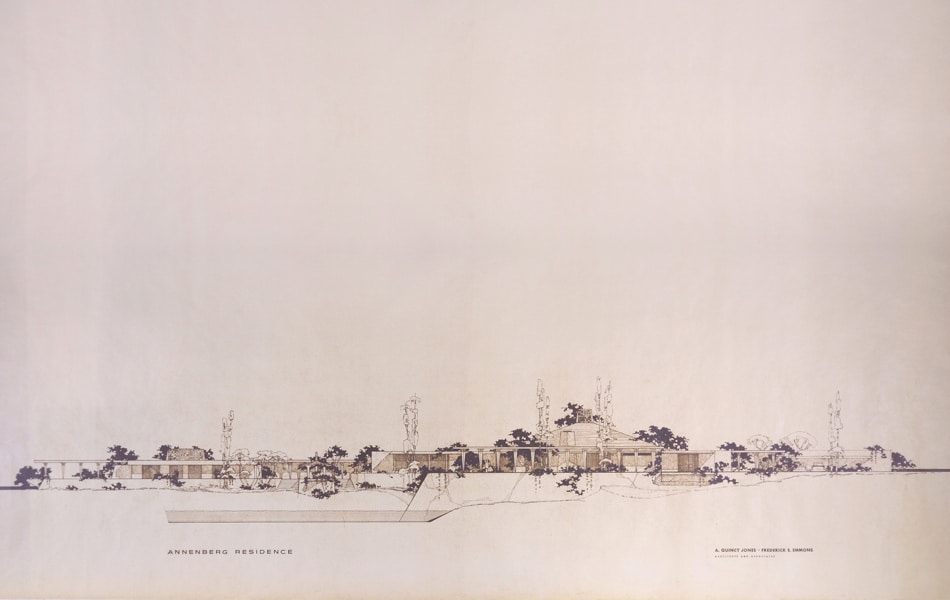

All of which makes Sunnylands, completed in 1966, a surprising addition to the list of the region’s modernist icons. It is, at 29,000 square feet, anything but modest. It bears little relationship to natural surroundings. (Instead, its 200 nearly bare acres were turned into a fantasy landscape, with 11 artificial lakes and a private golf course.) Its roof is covered in “peach parfait” tiles, and its furniture is lacquered and upholstered in bright greens, yellows and pinks. Most of all, its world-class collection of Impressionist and modern paintings, which require constant climate control, precluded easy indoor-outdoor living.

And yet, in her informative book Sunnylands: America’s Midcentury Masterpiece (Vendome), Janice Lyle makes the case that Sunnylands is, in the words of architectural historian David De Long, “a major example of mid-twentieth-century architecture specific to America.” It was certainly “a fresh paradigm of American glamour,” as interior designer Michael S. Smith writes in the introduction.

Guest bedrooms were known by their color. The Yellow Room’s prior occupants include President Ronald and Nancy Reagan, Colin and Alma Powell, Princess Margaret and Hillary Clinton.

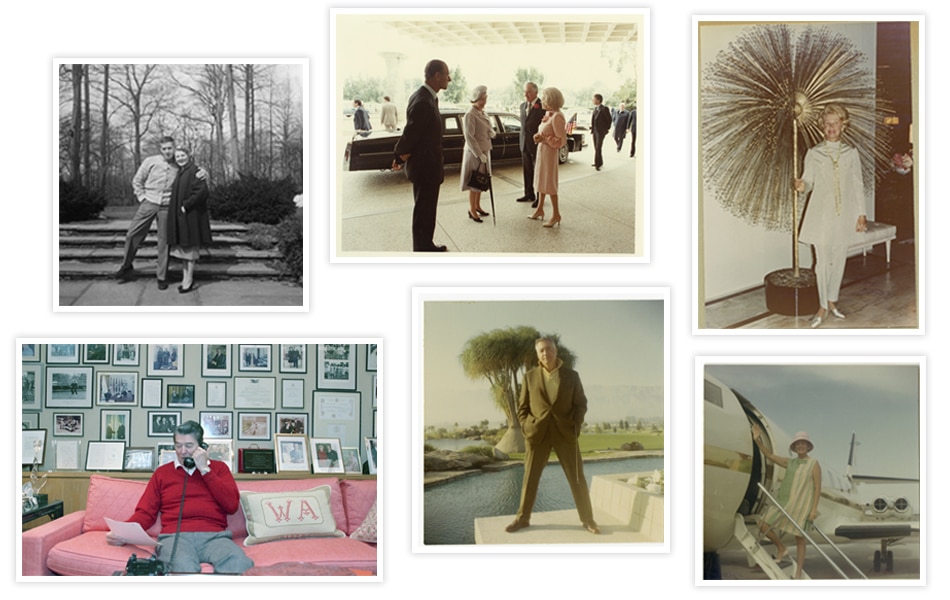

That glamour was the creation of Walter Annenberg, a publishing mogul who expanded his family’s media empire by creating TV Guide and Seventeen, and his wife, Leonore (Lee). They envisioned Sunnylands as a place where world leaders would gather, especially after Walter was appointed ambassador to England by Richard Nixon and Lee made Chief of Protocol by Ronald Reagan. The Annenbergs were nothing if not solicitous: When Dwight Eisenhower, the first of seven presidents to visit Sunnylands during the couple’s lifetime, commented on the absence of palms, they immediately added two large Washingtonia robusta trees to the Shangri-La setting. And they were nothing if not meticulous: They saved every bit of memorabilia, down to the personalized golf balls Nixon played with on their course. Luckily for readers of the book, the “private” moments at the house were captured by professional photographers. Important guests must have experienced déjà vu in the Room of Memories, lined with photos of important guests. The Rat Pack and the Brit Pack (including Queen Elizabeth) were visitors.

To design the house, the Annenbergs hired A. Quincy Jones, a noted L.A. modernist whose work embodied the postwar optimism and utility that marked in the Case Study House program. At Sunnylands, Jones worked to create as much of an open plan as possible, but he was foiled by the need for countless bedrooms and bathrooms and quarters for numerous servants. And the Annenbergs didn’t really have their heart in the open plan. In the 1970s, Lee had a new, formal dining room created from what had been a billiards room. And when the couple closed their “Main Line” house (a Norman-style mansion), outside Philadelphia, they re-created the ambience of one of its rooms, wallpapered in silk and filled with antiques, in the space that had contained an indoor pool. “I think the Annenbergs wanted something modern but not too modern,” Brooke Hodge, director of Architecture & Design at the Palm Springs Art Museum, recently told Introspective.

The landscaping at Sunnylands is a continuation of the pink-and-yellow color scheme that is used throughout the home. The rose garden included specialty varieties like “Nancy Reagan” and “Barbara Bush.”

Still, Jones created a striking building. The roof of its main pavilion resembles a Mayan pyramid. Below a central skylight stands an important sculpture, Auguste Rodin’s Eve, surrounded by a fountain and by planters filled with 300 pink-flowered bromeliads. Some walls are made of dark volcanic stone, a dramatic though never entirely fitting backdrop for paintings in ornate gold frames. But the house’s most-photographed feature may be its porte cochere, where a circular driveway passes under a stupendously deep overhang, allowing visiting dignitaries to arrive and depart while protected from the sun. The only thing missing was curbside check-in.

To furnish the house, the Annenbergs brought in William Haines, a former Hollywood actor who had turned to decorating and who is credited with inventing the Hollywood Regency style, a kind of movie-set version of Deco. (His early clients included Joan Crawford and Carole Lombard.) Haines designed some spectacular furniture for Sunnylands, and one of the real treats of the book is a series of vignettes in which Peter Schifando, who runs the firm Haines founded, describes the attributes of the Haines style. They include “unicorn” legs (metal furniture legs wrapped in leather in a spiral pattern) and “biscuit” tufting (a kind of extra-deep quilting, used prominently on a white Regency recamier in Sunnylands’ master bedroom). Another treat is found in letters from the erudite Haines to the Annenbergs; in one he tells Mrs. A that if he must obey her command to substitute “celadon damask for the off-white silk canvas covers on the sofa in front of the stone wall,” he will do so “sadly.” In its current incarnation, Sunnylands contains the only intact Haines interiors open to the public. Hodge says, “I particularly like Haines’s use of color in the house and have always thought it would be interesting to see how the colors connected to Lee Annenberg’s wardrobe.” This book, with its hundreds of color photos, many by Mark Davidson, makes it possible to do exactly that.

The view of the gardens in the spring is evocative of the Annenbergs’ collection of Impressionist art.

When Walter Annenberg died, in 2002, his collection of paintings was shipped off to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, leaving Lee to live with photo reproductions. Before her death, in 2009, she worked to turn the house into a conference center where important people would meet to discuss important things. She brought in Janice Lyle, then the executive director of the Palm Springs Art Museum, to help plan the transition; Lyle is now director of the Sunnylands Center and Gardens and the author of this book (a role that gave her access to fascinating archival material). Under Lyle, the house was treated to a gut renovation, a project that involved restoring it, she says, to its “period of greatest cultural significance — the 1980s Reagan presidency.”

As part of the $60 million upgrade, the landscape was significantly altered, partly to cut down on water usage. And a visitor center, designed by the Los Angeles architect Frederick Fisher, was constructed a bit north of the house on Bob Hope Drive in Palm Springs-adjacent Rancho Mirage. Fisher’s 2011 building, the starting point for some 90,000 yearly visitors, is an elegant, white-on-white pavilion with high ceilings supported on slender columns (almost as slender as the Alberto Giacometti Bust of Diego on display there). It looks more like an exemplar of mid-century modernism than does Sunnylands itself. Then again, Fisher didn’t have to accommodate the Annenbergs’ vast collections, ranging from those famous paintings to Steuben glass to presidents.

The bottom line: Sunnylands has little to say about the minimalism that characterized the best mid-century architecture. Like William Randolph Hearst’s San Simeon, it is sui generis — a monument to its owners’ aspirations. And if it never quite holds together architecturally, it is filled with details that make visiting Sunnylands, in person or via this book, worth every penny.