July 25, 2016Curated by the institution’s artistic director, Massimiliano Gioni (above, with Chris Burden’s 2009 1 Ton Crane Truck), “The Keeper,” at Manhattan’s New Museum through September 25, examines ideas of collecting, cataloging and chronicling objects, erasing some of the distinctions between art and artifacts along the way (portrait by Jesse Untracht-Oakner, courtesy New Museum, New York). Top: A detail of a still from Aurélien Froment’s 2007 video Théâtre de poche (Pocket Theater), in which a magician pulls disparate images out of his pocket, arranging them in midair around him. © Aurélien Mole

Massimiliano Gioni is one of the most respected arbiters of contemporary art around — a perennial name on power lists and, at 42, already a veteran curator of the Venice Biennale. But he’s also a rebel, having first gained real notice as prankster-slash-conceptual artist Maurizio Cattelan’s official impersonator. Along with curator Ali Subotnick, they cooked up all sorts of hijinks in the early aughts, including opening the Wrong Gallery, which occupied a doorway, and nothing more, in New York’s Chelsea gallery district.

The fact that Gioni now has a quite respectable job, as artistic director of the New Museum in New York, has not prevented him from slyly tweaking the art establishment. These days, he just has more real estate to exercise his ambitions.

His latest exhibition, “The Keeper,” which runs through September 25, confronts and even calls into question the very concept of a museum. The show, Gioni says during a break from installing it one warm summer day, is a “modest proposal:” “Museums should be less about confirmation of accepted notions of masterpieces and more places where objects speak — of the places where they came from, of the people who made them or found them.”

Most museums, he argues, oversimplify history into grand, but narrow, narratives. “The idea of the masterpiece is at this point complicit with the market, and it’s also very conservative and very oppressive to the viewer,” he says. “It doesn’t teach anything about the actual place in culture of that object. It just produces this fetish that people look at, stupefied. We need to do away with the distinction between art and non-art so that we can look at these objects as artifacts. Then we can discover the power of the artwork to connect us to people and specific moments in time.”

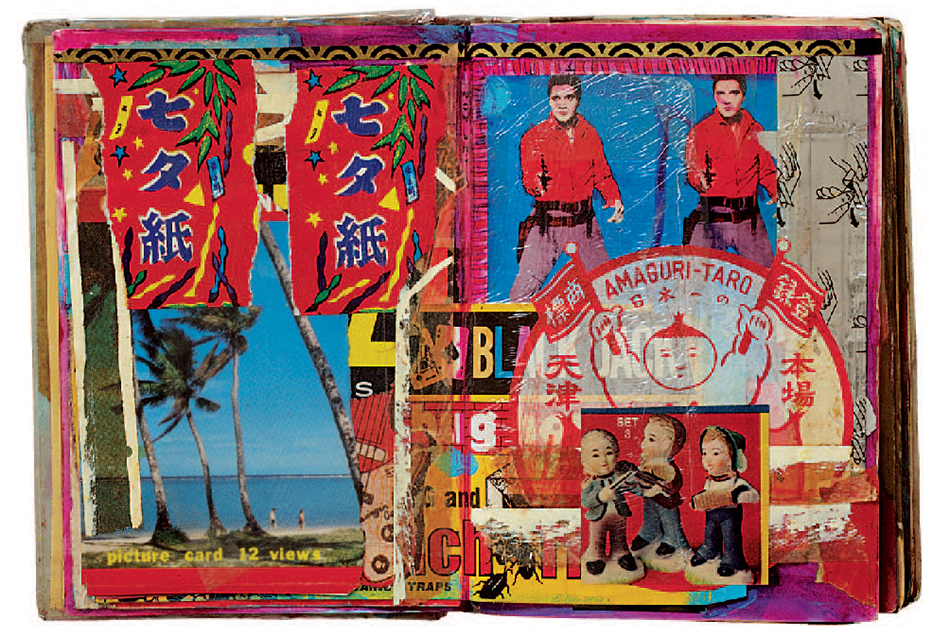

Densely packed with thousands of objects and images lovingly preserved by artists, collectors or hoarders — after all, isn’t one person’s collector another’s hoarder? — “The Keeper” is organized as several museums-within-a-museum, and it operates on numerous levels: It conveys the devotion of the various caretakers, questions what it means to be an artist and serves as a requiem both for artifacts being destroyed by war and for once-vital technologies that are now fading away.

Arthur Bispo do Rosário’s undated Carrinho-Arquivo II (Archive-Cart II) combines cardboard sheets, metal hooks, string, wood and wheels. A patient at a psychiatric hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Bispo believed he’d been called on by God to present to the deity at Judgement Day all the earthly goods he deemed worthy of salvation. He spent decades amassing objects that he combined into pieces such as this. Photo courtesy Museu Bispo do Rosário Arte Contemporânea/City Hall of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

One of the show’s museums-within-a-museum is Partners (The Teddy Bear Project) (2002), a trove of more than 3,000 family-album photographs of people posing with teddy bears along with vitrines displaying antique versions of the stuffed animals. Ydessa Hendeles, a longtime collector and curator, assembled Partners from flea markets as well as more modern points of sale, such as eBay. “The paradox,” notes Gioni in his Italian-inflected English, “is that this great monument to analog photography was actually achievable thanks to digital technology, no?” He first saw the project in Munich in 2003 and later showed it himself in the 2010 Gwangju Biennale he curated in Korea. (“People who have seen many of my shows might say I’m recycling my previous ideas,” he says with a contagious laugh.)

The photographs, primarily black-and-white, are particularly poignant. The imminent disappearance of analog photography is a recurring theme in “The Keeper,” which refutes the notion, popularized by Instagram, Snapchat and the like, that images are interchangeable. “The technology today has made us believe that one image can be replaced by another,” says Gioni, “and that whenever we throw away one, there will be more.”

The case of Ye Jinglu speaks forcefully to photography’s potency. Ye had a portrait taken of himself each of the 62 years of his adult life, creating a photographic autobiography. He died nearly 50 years ago, but the photographs were discovered and preserved by another man, Tong Bingxue, immortalizing Ye. “It’s such a simple gesture, but when you’re given access to all of them, it’s such a touching object that takes you through the life of a person in sixty-two images,” Gioni says. “It’s miraculous in the sense that you wouldn’t know this person if you didn’t have these images, but at the same time you have [only] the illusion of knowing him. Clearly, you know nothing about this person. You also start wondering how many other individuals you don’t know because no images were preserved. If you want the most romantic subtext of the exhibition, it’s, Who do we know and how, through which images they left behind?”

Among the more obsessive personalities featured in the show, Wilson Bentley attached a camera to a microscope in order to photograph snowflakes, ultimately making more than 5,000 photographs of them and showing that no two were identical. Photo courtesy Wilson Bentley Digital Archives of the Jericho Historical Society/snowflakebentley.com

The photos themselves, shot in portrait studios, do not rise to many viewers’ typical definition of art. But that, too, is the point. There is, Gioni says, a “blurring of the distinction between artworks and non-artworks, or the idea of looking at both as life stories. I didn’t select them with traditional notions of quality or value, high or low.

“A constant in my research is the idea that we should maybe do away with the distinction between artist and non-artist,” he continues. “The vast majority of people in this show are not artists. They’re more interested in saving something that will be lost.”

Handsome and slim, Gioni has had an emotional connection to art since he was a boy growing up outside Milan. Although enthralled with contemporary art, he merely flirted with making it himself. “I was playing around,” he admits. He stopped before he was 18. “I say I’m the first victim of my critical acumen.” Part of the problem, he suggests, was a youthful lack of patience and perseverance. “When I was doing something, I wanted to have it done. I couldn’t be bothered to go through the process.” That, he notes, may be why he often gravitates to artworks that took a long time to make.

Gioni concentrated on art history at the University of Bologna, figuring he’d be able to get a job as a high school teacher. Instead, he found his way into art journalism, becoming editor of the Italian edition of Flash Art. He moved to New York for the magazine in 1999. During his first few years in the city, art historian RoseLee Goldberg, who founded the Performa biennial of performance art, put him up. “We joke she gave me the RoseLee Goldberg Grant, because my salary was so small I couldn’t afford any rent,” he says.

While still living in Italy, Gioni had met and bonded with Cattelan, the art world’s class clown. Part of Cattelan’s shtick involved dispatching Gioni to do media interviews in his place. When both subsequently found themselves in New York, along with third musketeer Subotnick, now a curator at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, they haunted the galleries then springing up in Chelsea. Cattelan, Gioni recalls, decided they ought to have their own gallery since it seemed everyone else did. “The Wrong Gallery was meant to be a fridge with a door in an empty lot or a parking lot, so you would go, open the fridge and look at the artwork inside,” he says. “We learned there is a law in New York that you cannot abandon a fridge with a door because a child [could get trapped].” Cattelan noticed that next to Andrew Kreps Gallery, then on West 20th Street, was a recessed door leading to the basement. The trio convinced the landlord to let them install a glass door in front of it, creating the Wrong Gallery, the city’s smallest exhibition space, in 2002. Despite their “zero budget,” the friends managed to show dozens of artists and, after being evicted a few years later, moved the project to the Tate Modern in London.

Swedish Painter Hilma Af Klint, an early abstract artist, showed her work — which includes The Dove, No. 1, 1914–15, above — in the first part of her career before deciding that her pieces should not be displayed publicly until two decades after her death. Photo courtesy the Hilma af Klint Foundation

Meanwhile, Gioni had shifted from art criticism to curating, and his reputation ballooned. In quick succession, he helmed Manifesta, the Berlin Biennial and Gwangju before being tapped for the 2013 Venice Biennale. He joined the New Museum in 2006, as director of special exhibitions. In the past decade, he has been instrumental in elevating the New Museum within the city’s museum landscape, spearheading its triennial as well as such acclaimed monographic shows as those devoted to Nicole Eisenman and Chris Ofili.

Although “The Keeper” is dotted with a few of big names like those, including contemporary artist Carol Bove and butterfly enthusiast and novelist Vladimir Nabokov, most will be discoveries for the museum’s audience. Susan Hiller, for instance, collected 25 dying or lost languages in a video, The Last Silent Movie (2007), which consists of only audio clips and white text on a black screen. The self-taught Richard Greaves constructed wildly inventive, strangely mesmerizing would-be houses in rural Quebec from architectural detritus, consumer goods and twine. They were not habitable and always looked precariously close to collapse, but before they succumbed to gravity or the elements, Mario Del Curto captured their existence with his camera.

Other artists in the show exhibit extreme eccentricity and near monomania. Korbinian Aigner, an antifascist Catholic priest devoted to growing apples and pears, which he continued to cultivate even when sentenced to forced labor at the Dachau concentration camp, made more than 900 postcard-size paintings of his beloved fruit. Wilson Bentley tracked the weather in his native Vermont daily and rigged a camera to his microscope so that he could photograph snowflakes, eventually making more than 5,000 images and discovering that no two snowflakes are exactly alike. Beginning at the age of 67, Zofia Rydet attempted to photograph every household in Poland. She managed to shoot nearly 20,000 before her death 19 years later.

Howard Fried began his ongoing The Decomposition of My Mother’s Wardrobe in 2014. In the gallery setting, the piece presents a careful installation of the clothing of his deceased mother, seen behind glass. An interactive element allows invited participants to take an online survey that matches them with several items from the wardrobe, one of which they may then select to keep as their own. Photo by Fredrik Nilsen, courtesy the artist and The Box, Los Angeles

Then there’s Hilma af Klint, a Swedish painter and pioneer of abstract art who, after exhibiting early in her career, decided to keep her work private, going so far as to stipulate in her will that her output of more than a thousand paintings could not be displayed publicly until 20 years after her death, which occurred in 1944. “With her, you have an example of a person who is preserving something, almost to the point that it becomes counterproductive toward her own career,” Gioni says. “In that gesture, to me, there is both a discipline and a sense of sacrifice that still escapes me today.”

Af Klint’s life may hold a valuable lesson for today’s young artists, who are pressured to be highly visible, he says. “Here we have a person who consciously decides to be invisible. Maybe she became a mythical figure because of that refusal.” He mulls a moment. “That’s also an interesting strategy of visibility.”

Not only artists must confront the dilemma of fame. A prominent art dealer was once quoted in the New York Times calling Gioni a “brand.” He meant it as a compliment.

“It’s a paradox,” Gioni admits when asked about the description. “I cannot be naive about the role I play in the art system. I can be very critical of a narrow understanding of collecting” — an economic one — “but at the same time there are people out there who say I belong to the same world. I think things are more complicated than that.” Even his goal of “expanding certain canons,” he realizes, could be read cynically as “very conducive to the market.” But, he says, “I’m not flipping works. I’m not increasing the value of these works. I hope I’m increasing the emotional value.”

As for his own art-acquisition habits, Gioni says he and his wife — Cecilia Alemani, the director and curator of High Line Art — steer clear of collecting themselves. In fact, they have almost no art at home, feeling, as another curator has put it, that hanging art on their apartment’s walls would be like a doctor coming home to a house full of blood. “Now we have a baby,” Gioni says, “so that’s mostly what we look at.”