April 29, 2018The Paston family were hoarders of global proportions, and they made sure to leave behind proof. Cosmopolitan patriarch William Paston (1610–63), who had the title first Baronet and traveled to places like Italy, Holland, Egypt and the Holy Land, and his son Robert Paston (1631–83), the first Earl of Yarmouth, collected everything from Indo-Pacific snail shells to 12-string lutes to ornate Dutch silver. All these items — many stored in the family’s “best closett” at Oxnead Hall, a sprawling Elizabethan estate in Norfolk — were recorded by an unidentified artist in the strange and masterful painting The Paston Treasure, circa 1663.

On view at the Yale Center for British Art until May 27 and heading to England’s Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery in June, “The Paston Treasure: Microcosm of the Known World” reunites the painting with five vessels featured in the composition, displayed alongside portraits, letters, architectural drawings, alchemical recipes, jewelry and musical instruments related to the painting and the Paston brood.

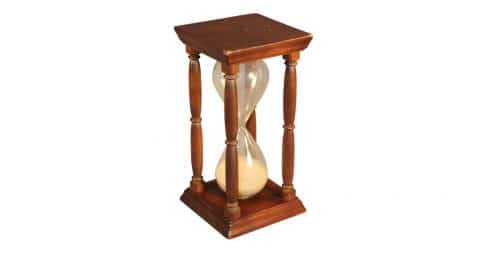

Technically, The Paston Treasure is a still life, and the painter took pains to include as many of the Pastons’ favorite pieces as he could fit on and around a hefty larder table. Mature flowers, ripe fruit, ticking timepieces and a snuffed-out candle are there to remind us that we all, someday, will die.

The painting also has portraits of Robert’s daughter Margaret and a young man of African descent. (X-rays reveal that a woman once stood on the right side, but she was later replaced by a wall clock.) Everything is realistically depicted, although the space is distorted and flattened as in a dadaist collage. It’s majestic and confusing at once. For instance, why is that lobster seemingly fading into oblivion?

And speaking of oblivion, a series of unhappy happenstances, including the Parliamentarians’ victory over the Royalists in the English Civil Wars and the scattering of William’s wealth after his death, led to a gradual deterioration of the Pastons’ fortune and home. Both Robert and Margaret turned to alchemy in an attempt to create gold by their own means. Nonetheless, the painting survives to remind us how rich this family once was.

Here, five experts from Yale and Norwich Castle give us a tour of The Paston Treasure and tell us why it’s worth treasuring today.

Young Man

“It is not clear if the young man in the painting was a real person known to the Pastons or a generic figure inserted in the composition by the painter. He is almost certainly based on an actual likeness. His rich, almost theatrical costume includes a striped sash of a fabric made in Norwich known as callimanco, which is tied across his middle — possibly a clue that this was the portrait of a local. If this young man was a member of the Paston household, he was likely a servant or a slave — a reminder that The Paston Treasure emerged in an age of colonialism and imperialism.”

— Nathan Flis, Head of Exhibitions and Publications, and Assistant Curator of 17th-Century Paintings, Yale Center for British Art

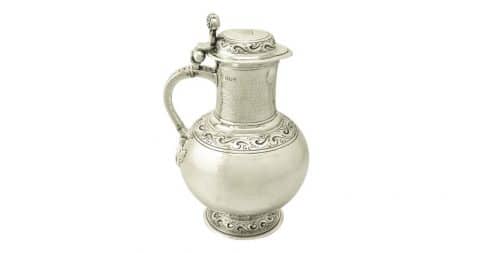

Flagon

“The precious objects in The Paston Treasure were certainly painted from life. The artist made a careful portrait of each collection object, capturing subtle shifts in the iridescent shells, nuances in the gold and silver work and details that could easily be overlooked were he working from sketches — for example, the silver hallmarks on the flagon held by the young man.”

— Jessica David, Senior Conservator of Paintings, Yale Center for British Art

Trumpet

“The silver trumpet is traditionally associated with fame. It could well have belonged to the Pastons. It was usual for servants to announce the arrival of important citizens or family members by sounding trumpets, as in an ancient Roman Triumph parade. This may account for the young man’s masquerade Roman style of costume. It would not have been played in a chamber concert with the other instruments in the painting.”

— Andrew Moore, former Keeper of Art and Senior Curator, Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery

Shell Cups

“By including shells brought from the depths of far-flung oceans cast into mounts fashioned by the hands of the most talented European goldsmiths, the painter showed that Sir William Paston owned what were considered the highest forms of natural and artificial achievement.”

— Edward Town, Head of Collections Information and Access, and Assistant Curator of Early Modern Art, Yale Center for British Art

“One cup, in front of the black mirror, has the arms of William Paston incised in black on the nautilus shell. This now belongs to the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, although the shell has been replaced. Another also bears the Paston arms, although it can only be seen in the shell cup itself, on loan from the Museum Prinsenhof Delft.”

— A.M.

Lobster

“The strangely pink lobster has undergone pigment change. Once vermilion red, it is a typical device for still-life painters to indicate wealth at the table. William Paston was a great consumer of local lobster, and so a specimen could well have been at hand.”

— A.M.

Claw-Footed Cup

“There is possible alchemical symbolism within the picture which could chime with the interests of Robert Paston. For instance, the engraving on the claw-footed shell cup depicts a running figure who has been identified as a version of Atalanta. She has been adapted from an illustration to the extraordinary alchemical work Atalanta Fugiens, or Atalanta Running, 1618, by Michael Maier, which brings together words, images and music to explain alchemical concepts. Is this image of Atalanta, striving towards victory, intended to mirror the aims of Robert Paston as he sought his elusive Red Elixir [which he thought could transform base metals into gold]?”

— Francesca Vanke, Keeper of Art and Curator of Decorative Art, Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery

Girl with Music Book

“The girl’s hairstyle was fashionable in the early 1660s. We believe she is William Paston’s favorite granddaughter, Margaret, aged about twelve years old when her grandfather died, in February 1663.

“Margaret sings from a music book, and the notation has been recently identified and reconstructed as a Charon dialogue by the Cambridge composer Robert Ramsey, circa 1630. Charon rows souls across the river Styx to enter the underworld. This, along with the watch, clock, sandglass and guttering candle, is an intimation of death in the painting. Such imagery is typical of the vanitas tradition of still-life painting, reminding us of the vanity of human possessions in the face of death.”

— A.M.

Monkey and Parrot

“It is tempting to think of the West African vervet monkey and the African grey parrot as household pets, but they more likely symbolize trade with Africa, an exotic land at this time.”

— A.M.

“The animals and other still-life objects were drawn from extant sources that the artist had brought with him, including the painting Monkeys & Parrots, from around the 1660s, which is also featured in the exhibition.”

— J.D.

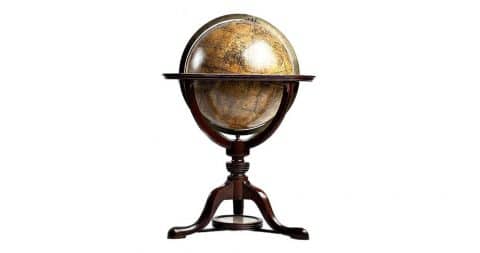

Globe

“The table globe was one of two owned by William Paston. It is so carefully painted it has been possible to identify the makers as Pieter van den Keere and Petrus Plancius. There are four editions of the globe, dating to between 1614 and 1645. The sketchy nature of the western coast of North America northwest of California was as accurate as could be at the time.”

— A.M.

“The globe, a high-quality example from Amsterdam, could be a prominent reference to William’s wide-ranging journeys. William himself, who was in Holland in the early 1640s, could have bought it there, along with the many other Dutch items he amassed at the time.”

— F.V.

Lute

“The unusual form of the two-headed lute enabled extra pairs of strings and dexterity. This form of lute was invented by the French lute player and composer Jacques Gaultier (active 1617 to 1652), possibly in England, where he was the foremost lutenist.”

— A.M.

Clock

“The diamond-shaped clock was a new invention in the early 1660s. It has only one long hand to point the hour but was still regarded as highly reliable, needing to be wound only once a week. It is likely to have belonged to the Pastons and not be simply an imaginative creation.”

— A.M.

“Changes in the composition in the right-hand corner of the painting hint at discord in the Pastons’ domestic world. Bad blood between Robert Paston and his stepmother [William’s second wife], Margaret, led William Paston to devise a special provision in his will whereby his best objects were divided into two parts: Margaret was to decide how the objects should be divided, and then Robert was to have his pick of which half he would keep. This sought to ensure an even distribution of the most coveted objects, such as the large silver dish, which is also mentioned in William Paston’s will of 1662.

“It is surely not a matter of coincidence that a silver dish once occupied the right-hand corner of the composition before being replaced by a portrait of a woman, which in turn was abandoned in favor of the clock and bookshelf. In this sense, The Paston Treasure depicts both the very best and the very worst of the family’s history. Their world was larger than that of most who lived in the seventeenth century, but in the aftermath of William Paston’s death, in 1663, it rapidly became uncomfortably small.”

— E.T.

Setting

“The table and background were painted last, around all the forms when they were basically finished and dry. The composition is, therefore, a combination of life painting, recycled sources and imagination.”

— J.D.

Pigments

“The Paston painter used upward of twenty different pigments in its making, which is significantly more than would have been deployed by contemporary still-life painters, and his use of pigment mixtures is completely unique. Expensive materials like ultramarine and azurite blue were expended on insignificant ‘filler’ parts of the composition, while inexpensive blue smalt, a pigment known to degrade swiftly, was applied to all silver passages, including several of the ‘treasure’ items.

“Orpiment, an arsenic-based yellow pigment, was used on all gold objects, although the painter would have anticipated its incompatibility and rapid discoloration in combination with adjacent colorants. This suggests that, despite the artist’s evident knowledge of his craft, his use of materials was at best eccentric.”

— J.D.

All photos: The Paston Treasure, ca. 1663, oil on canvas, by an unknown artist of the Dutch School. Courtesy of Norfolk Museum Services