June 1, 2025Thierry Despont designed houses for some of the world’s most discerning clients. Having studied at both the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the last bastion of classicism, and Harvard’s Graduate School of Design when modernism was the sanctioned style, he could work in any idiom. The minimalist Calvin Klein and the maximalist Ralph Lauren were both devotees of the erudite New York–based architect.

Despont also restored monuments, from the Statue of Liberty, in New York Harbor, to the Vendôme Column, in Paris. He refurbished the column’s neighbor, the Paris Ritz, and redid Claridge’s, in London. He designed the decorative-arts galleries at the Getty Museum, in Los Angeles. In Manhattan, he revamped the Carlyle Hotel, the Palm Court at the Plaza and the flagship Cartier store. Downtown, he turned the landmark Battery Maritime Building into Casa Cipriani and the Woolworth Building into residences.

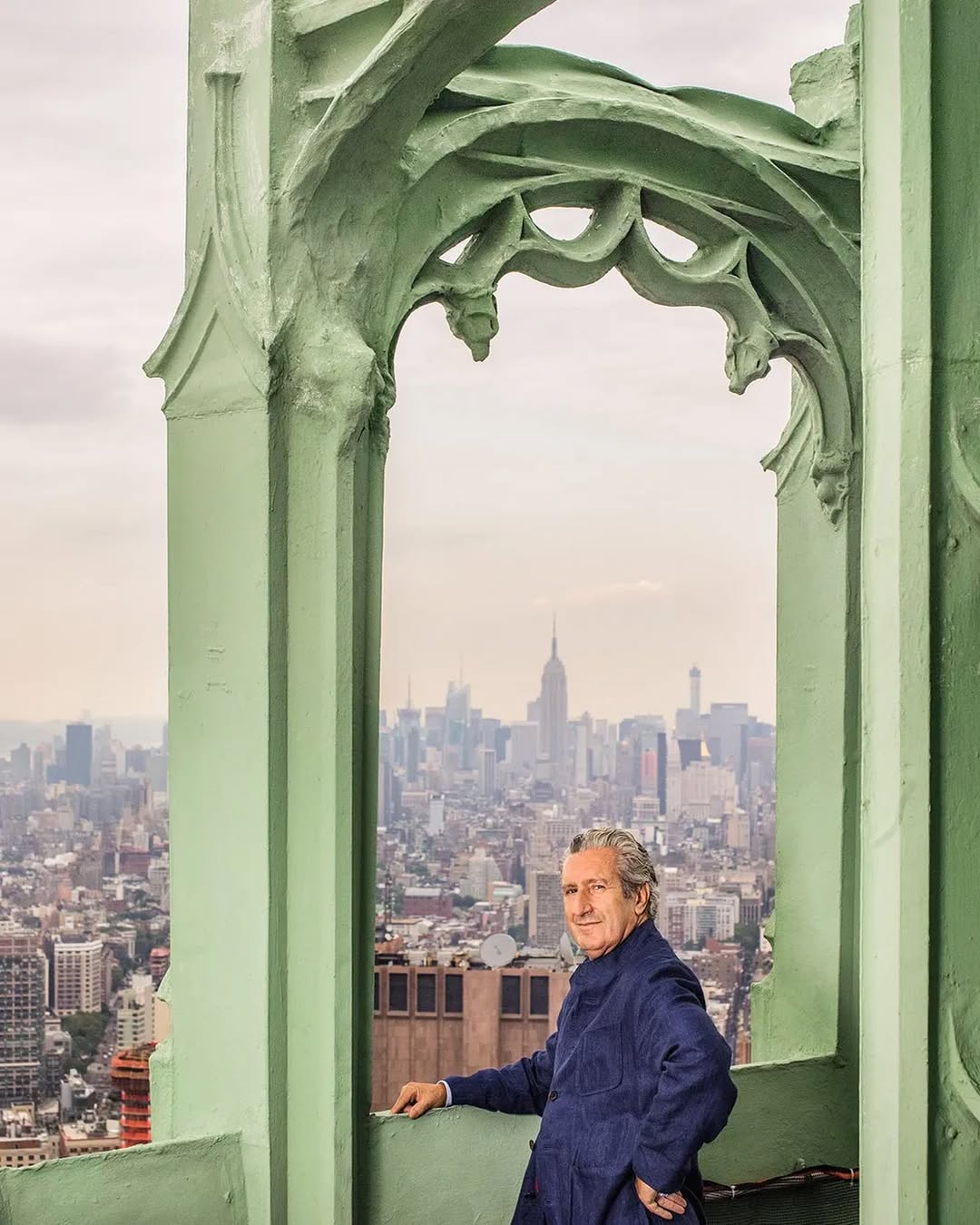

Yet somehow, Despont, whom the New York Times once described as “a dashing man with the swagger of a matinee idol and the profile of Louis XIV,” had time for a second career. As an artist, Despont produced a number of extensive and distinct bodies of work.

One was a series of extraordinarily vibrant paintings of celestial bodies, including the moon — silver in one version, bright red in another — and several equally resplendent planets.

Works on paper included life drawings, self-portraits, portraits of some of his heroes (including the poet Arthur Rimbaud) and even pencil-and-watercolor renderings of fish.

Despont was also a master of art in three dimensions. Echoing Picasso, Calder and Duchamp, he turned old tools, plumbing parts and other found objects into a menagerie of mythical creatures. They range from small ersatz insects in glass boxes to beasts large enough to confront visitors tête-à-tête.

Some of Despont’s works enhanced the homes he designed for clients, some were sold through the Marlborough Gallery (now closed), and some helped turn his studios in Manhattan and Southampton, on Long Island, into rich, layered environments. “He never occupied a room that wasn’t carefully curated,” says his daughter Louise, herself an artist.

When Despont died, in 2023 at 75, it fell to Louise and her sister, Catherine, to decide how best to distribute his art. “They wanted it to be seen — they didn’t want it sitting in a warehouse,” says Benoist F. Drut, the proprietor of Manhattan furniture gallery Maison Gerard, where Despont was a valued customer and respected as a fellow aesthetic adventurer.

So, when Louise and Catherine wrote to him about selling their father’s work, Drut immediately “answered from the heart,” he says. He committed to showing as much of Despont’s oeuvre as he could fit in Maison Gerard’s gallery at 53 East 10th Street and its newly acquired 18,000-square-foot space on the top floor of the Falchi Building, in Long Island City, Queens. The exhibition, called “Thierry Despont: Modern Renaissance Man,” will fill both locations starting on June 4. (Some 50 pieces from the show are now exclusively available on 1stDibs, which is fitting, since Despont was a regular 1stDibs customer.)

Drut’s efforts go beyond filling his galleries with Despont’s work. He is, to the extent possible, re-creating the feel of Despont’s studios, using the architect’s own furniture, which includes club chairs in leather so soft it feels like silk and tables made from beams Despont removed from his Manhattan office to create a room tall enough for his art. There are pieces designed by Despont in the style of Paul Dupré-Lafon and Jules Leleu and others by makers the architect admired, such as Vibo, Maison Dutruc-Rosset and Woka Lamps. There are also unattributed pieces, notably the bare metal benches that had graced his office waiting room. And there are objects he collected, ranging from a signed model of the Statue of Liberty’s torch to a 1934 Bally Skyscraper pinball machine. The show will be the last best chance to get a sense of Despont’s talent for imbuing every space he touched with grandeur, poetry and whimsy.

To Louise and Catherine, the bug sculptures are particularly meaningful. Despont’s father collected insects, and as a boy, Despont used twigs and leaves and other bits of nature to mimic his father’s specimens. He continued creating such assemblages until his death. “Making things,” Catherine says, “was how he played.”

Also on view will be several cabinets of curiosities: display cases filled with all manner of trinkets and treasures. The largest cabinet — more than 12 feet wide and 9 feet high — is dubbed the Bibliotheca Selenica (Lunar Library). It contains a world-class collection of research material about the moon. There are more than 200 books, including a second edition of Galileo Galilei’s Sidereus Nuncius, originally published in 1610, as well as manuscripts, etchings, maps and even a computer archive of the printed matter. “It was the last cabinet he created and by far the most comprehensive work of art and collecting he ever made,” says Drut.

It will be impossible to leave Maison Gerard without a new appreciation of Despont’s art and its ability to make all kinds of rooms more interesting. As Despont said of an installation of his work in 2013: “You might come away thinking, ‘Maybe I can live with paintings of planets or with insect sculptures,’ no matter what style your house is. And you also think, ‘Maybe I should not have thrown away my grandfather’s old tools.’ ”