Among Tomaso Buzzi’s stylistic innovations at Venini were his distinctively hued incamiciato pieces, adorned with gold leaf, and often decorated with whimsical creatures, as seen above and at top. A selection featured at the 5th Milan Triennale, in 1933, obtained the Grand Prix. All photos by Enrico Fiorese

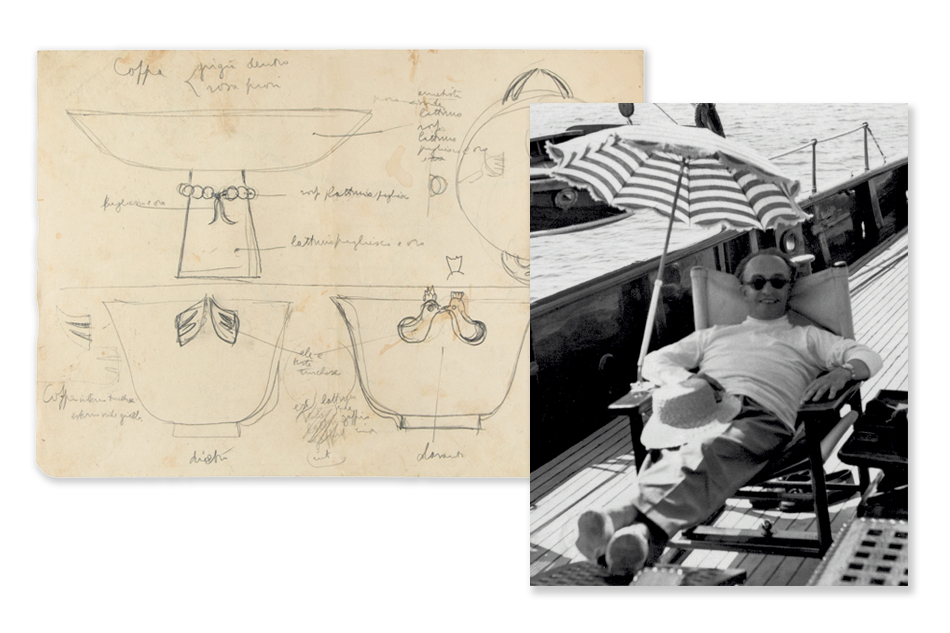

September 7, 2015Paolo Venini founded what would become the preeminent Italian art glass manufactory of the 20th century, but in early 1932 he was in a terrible bind. A trained lawyer with an entrepreneurial spirit, Venini had entered the glass-making business 11 years before, determined to offer aesthetically simpler and lighter wares than the ornate, overwrought work that had become the norm on Murano — the island in the Venetian lagoon that has been the center of Italian glass artistry since the 13th century. Venini had known troubled times before — in 1925, his first partner in the glass business had decamped to open a rival company — and now seven years later Venini’s artistic director, the sculptor Napoleone Martinuzzi, had left to start his own firm. Though Venini would later demonstrate his own talents as a glass designer, in 1932, in the midst of a global economic depression, he was desperate to find someone with the skills and eye to appeal to his firm’s discerning upper-class clientele. He turned to a maverick young architect named Tomaso Buzzi.

The fruit of that collaboration is the subject of a new book, Tomaso Buzzi at Venini (Skira, $90), edited by the historian and curator Marino Barovier, himself a member of a distinguished Venetian glass-making family. Though Buzzi’s tenure at Venini lasted a scant two years, this handsome and illuminating book — thick with scholarly-yet-engaging essays and abundantly illustrated with new color photos, historical images, and Buzzi’s buoyant design sketches — testifies to the richness of that period. Historians and collectors say that attention is overdue for Buzzi, who in addition to his work in architecture and glass designed furniture, landscapes, lighting, textiles, jewelry and ceramics. “Tomaso Buzzi is often overlooked and undeservedly so,” says Tina Oldknow, senior curator for modern and contemporary glass at the Corning Museum of Glass. “He is one of the most remarkable and inventive members of his generation of Italian designers. At Venini, he created some of the most elegant and sophisticated designs the company ever produced.”

Boccia dei cavalli marini (Vase of the Sea Horses) is another example of Buzzi’s incamiciato pieces in the alba hue he specially devised with Venini’s glassblowers.

Buzzi was born in 1900 in the town of Sondrio in the Lombardy region of northern Italy. He studied at the Milan Polytechnic, and soon after he graduated joined a lively Milanese decorative-arts scene that included the great glass designer Pietro Chiesa, architect Emilio Lancia and architect and editor Giò Ponti, the central figure in 20th-century Italian design. With several others, they formed the core of a design movement known as the Novecento Milanese — an approximate equivalent to the Art Deco stylistic school of France. Like their counterparts in Paris, such as Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann and Armand Rateau, the Milanese produced modern interpretations of 18th-century furnishings, inspired by the strong, stately lines of the neoclassical (or Louis XVI) period, and to a lesser extent the sensuous curves of the rococo. In addition to collaborating with Ponti on the design magazine Domus, Buzzi also teamed up with him on several interior design projects and, as shown in Barovier’s book, many of their robust, symmetrical tables and chairs would look as suitable in a Right Bank hôtel particulier of the day as in a Florentine villa.

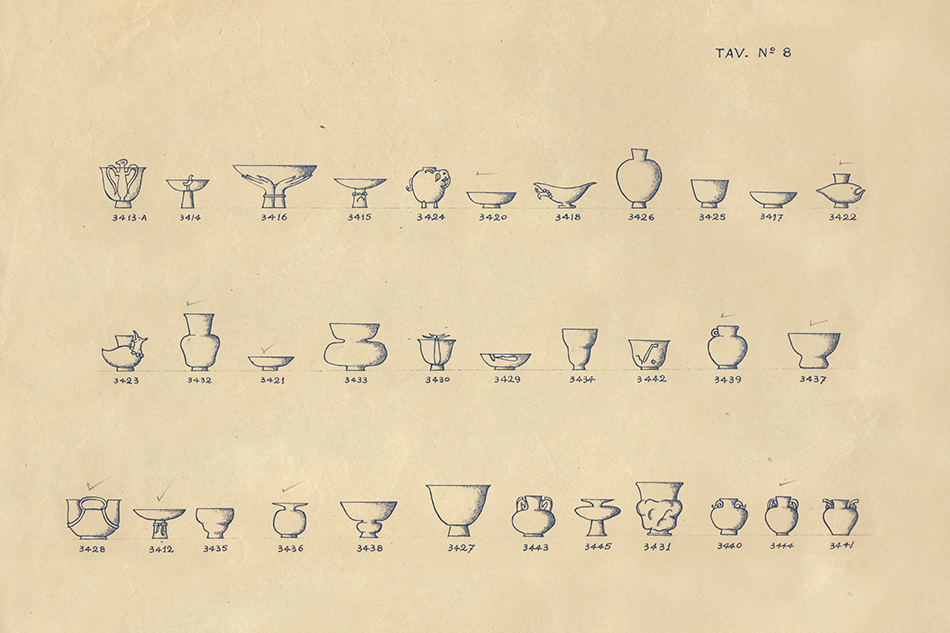

Working for Venini, Buzzi would delve much, much further back in time. Buzzi had a deep interest in archaeology, and based numerous vases on the forms of ancient Persian bronze and silver hollowware. Some of Buzzi’s most affecting designs for Venini were modeled after single- or double-spouted Etruscan vessels — used to hold oil or other costly liquids — in animal shapes. But Buzzi’s very best forms sprang from his own rich imagination — a cup with a tiny bird on a pedestal in the center of the bowl; a vase with handles in the shape of stocky unicorn heads; and what many regard as his masterpiece in glass: the Coppa della Mani, a wide cup set on a base in the form of two outspread hands. “Buzzi was very, very creative and it’s the little additions — the bird, the unicorn heads — that make his designs so attractive. These were delicate, difficult pieces to make,” says Howard Lockwood, a glass historian and noted collector. “Paolo Venini deserves credit, too. He allowed his designers the leeway to take risks and try anything — and most of the time it paid off.”

At the 18th Venice Biennale, in 1932, Venini presented Buzzi’s turchese e nero series in the new decorative arts section. Its sleek lines and striking color pairing caused a sensation, and Italy’s King Vittorio Emanuele III acquired a piece.

Buzzi also had a keen eye for colors, both vivid and subtle. His first collection for Venini, presented at the 1932 Venice Biennale, included his turchese e nero series: vases and a dish with bright turquoise bodies and black rims and bases and, in a few examples, applied figurative motifs. The pieces were a sensation; King Vittorio Emanuele III bought one during his visit to the show. Working with Venini’s master glassblowers, Buzzi had a particular affinity for pieces made with the incamiciato (or casing) technique, in which layers of glass in contrasting colors are applied atop one another to create a lustrous final hue. “Buzzi devised recipes using from seven to twelve layers of glass, with pieces of gold leaf in between, to achieve deep, glowing colors,” says Marc Heiremans, the noted Brussels-based dealer of Italian glass. “The layers are so thin that the pieces remain remarkably light.” The Barovier book includes fascinating diagrams showing the layering formulas that result in Buzzi’s three signature pastel colorways: laguna, a spectrum of hues that runs from pink to peach; alga, a sort of sea green; and alba, a grayish blue.

Although the most complex pieces Buzzi created for Venini are exceedingly rare, of all the areas of the applied arts in which he worked, glass may offer the most obtainable specimens. “Other designers of the period, such as Giò Ponti, embraced large-scale manufacturing. Buzzi did not. Most of his work was for custom commissions,” explains James Harrison, gallery director for the Manhattan antiques firm H.M. Luther. “Examples of Buzzi’s simpler vases based on Asian forms, however, are relatively accessible.”

Buzzi left Venini in 1934 and spent the remainder of his career working primarily on architectural projects for a clientele of wealthy and aristocratic Italians. He died in 1981. “I don’t think Buzzi was completely married to glass — he had so many interests — and Paolo Venini needed someone more committed,” says Lockwood. That is a typical quirky twist in the history of modern Italian glassware — a field of collecting rife with arcana, and one that rewards study. Barovier’s book is one of a series on Venini designers he has edited for Skira — previous works have covered Martinuzzi and Carlo Scarpa, who took over as the firm’s artistic director when Buzzi departed and stayed until 1947; a volume on the company’s great postwar designer Fulvio Biancone is due out this fall. Tomaso Buzzi at Venini merits a place in the library of any glass collector, novice or veteran.

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

or support your local bookstore