September 29, 2024It is hard to pigeonhole Ben Pentreath, frequently described as the go-to architectural and interior designer of the British royal family. Yes, he has worked on several urban-development projects with King Charles, including a park-and-ride system in Truro, Cornwall, and a newly developed, classically styled town called Poundbury, in Dorset, which will eventually have a population of 6,000. And he is widely reported to have helped the current Prince and Princess of Wales with the refurbishment of Anmer Hall, a 10-bedroom Georgian mansion on the Sandringham Estate, in Norfolk, as well as with their apartment at Kensington Palace.

But his multidiscipline London-based practice, which employs more than 40 people, serves a broad spectrum of clients, both private and public, on projects running the gamut from town planning to interiors. “On a normal day,” Pentreath has said, “I might be leaving a meeting where I was discussing cushion pipings or what pillows people are having on the sofa, and I will then be going into one where we’re laying out street networks or talking about below-ground drainage.”

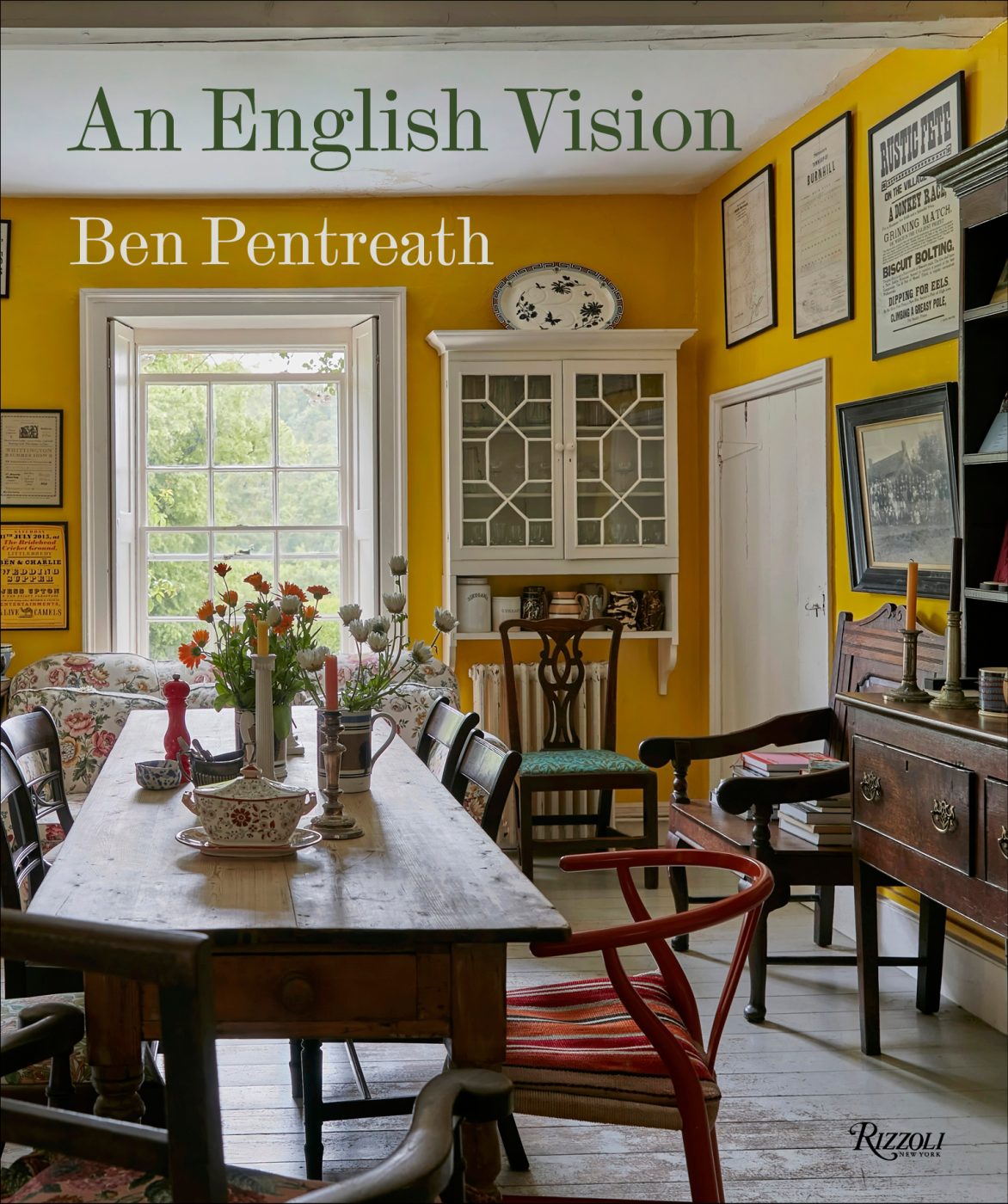

In his portfolio is everything from a new town in Scotland called Tornagrain, for which he is both master planner and architectural designer, to eclectically decorated London apartments and grand residences, such as a rebuilt Jacobean castle in Cornwall and a most impressive English baroque house in Dorset called Chettle. All can be seen in his new Rizzoli book, An English Vision, for which he not only wrote the text but also took all the photos.

Readers will also find in its pages a series of Pentreath’s own residences, shared with his husband, New Zealand–born gardener Charlie McCormick, including an 1820 parsonage in Dorset, a flat occupying the two top floors of a building overlooking Queen Square in London’s Bloomsbury and a pair of neighboring, incredibly modest stone-walled houses on the west coast of Scotland. He writes that the last are “the epitome of architectural happiness for Charlie and me.”

They are a far cry from the splendor of regal residences. Belonging to the category of small huts or cottages the Scots call bothies, they are located in the middle of nowhere, on a single-lane road, overlooking an estuary near the tip of a peninsula. One dates to the 18th century, the other to the 19th, and both were in a state of serious disrepair when Pentreath and McCormick discovered them after searching for four years for a simple house by the sea and in an unspoiled landscape. The roof of the older one had collapsed, and locals had used it for years as a garbage dump.

They initially just installed new windows and doors, equipped the hut with a new metal roof and designated it the kitchen. “The first year, it was arctic, unbearable,” Pentreath tells Introspective. “We’d go there in the morning, and if we’d left a jug of water, it would have frozen overnight.”

The indoor temperature has risen slightly since, thanks to the addition of a timber ceiling. The other structure, built a hundred or so years later, was in marginally better shape, still sporting its original Victorian-era match-boarded pine paneling. Pentreath earmarked it to house the sitting room and bedroom.

Household comforts are still rudimentary. The couple get their water in a bucket from a spring, rely on a composting toilet and have to “de-mold” the older building frequently. Pentreath quips that living there is “like being in a stone tent,” but he loves the remoteness. “The emptiness is part of the appeal,” he says, “and there are the most astonishing and varied landscapes.”

Pentreath’s ties to Scotland date back to his teenage years. His father was in the Royal Navy and was stationed during the 1980s in the town of Helensburgh — located to the north of Glasgow and best known as the location of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s architectural masterpiece, Hill House.

Pentreath later studied art and architectural history at the University of Edinburgh before attending the short-lived Prince of Wales’s Institute of Architecture, in London. He says the monarch’s traditionalist views have had a profound influence on his thinking and clearly recalls as a teenager watching the 1988 TV documentary Charles: A Vision of Britain, in which the now-king famously declared that the brutalist Birmingham Central Library resembled “a place where books are incinerated, not kept.”

“It was an electric moment for me,” Pentreath says. “It tuned into how I was feeling about buildings, even at that young age.”

The buildings and towns he designs today are almost exclusively classical in style and look as if they’ve been in place for decades, if not centuries.

“There is generally nothing that hasn’t been beautifully and elegantly solved by an architect or builder in history,” he writes in An English Vision. “I love to draw inspiration from the past, often more directly than you can imagine.”

You could be forgiven for believing that he hates all modern and contemporary buildings, but it’s actually mundane, mediocre urban environments that he despises. He loves “a good sixties tower block,” as well as Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’s inside-out Pompidou Center. “It sets up an incredibly exciting visual conversation with surrounding Paris,” he says.

His interior design, too, is rooted in the past and the great tradition of English decorating. His rooms tend to look laid-back, lived-in and eclectic. A good example, featured in his book, is the home of cook and writer Skye McAlpine and her husband, Anthony Santospirito, in the London borough of Wandsworth. In the dining area, he installed a long 19th-century French wooden table and a tall glass-doored cupboard, which he painted gray and lined with an Antoinette Poisson paper.

Pentreath also loves to play with color and to take risks. In a largely calm and neutral-toned apartment on London’s York Terrace, he adorned the walls of the hallway with an emerald-green faux-malachite motif.

In another project, a Regency-era house in the south of England, he used muted, sorbet-like hues of coral, celadon, citrine and aqua for ruched lampshades, fringed sofas, piping-trimmed armchairs and flowing draperies. The result, Pentreath writes in the book is “an interior defined by a powerful yet balanced sense of colour: not quite historical, not quite modern.”

When it came to decorating the interiors of the bothies, Pentreath’s goal was to inject “a very strong nineteenth-century flavor.” He placed a period washstand designed by Augustus Pugin (best known for the interiors of the Palace of Westminster) in the bedroom, and he used an antique-looking Jean Monro chintz fabric called Camilla, for the curtains, armchair and sofa in the sitting room. The interiors also display a selection of pieces from his collection of Victorian Staffordshire figures, which he loves partly for what he refers to as their crudeness.

“I think they shocked tasteful people in the nineteenth century,” he says. “It’s very vernacular, not very well-designed, not very well-made.” In his mind, an element of imperfection is essential in any interior.

Scottish touches abound here, from the sailing charts of the west coast and the array of Wemyss Ware, the country’s most famous pottery, in the sitting room to the majestic high-backed Orkney rush chair to one side of the kitchen fireplace. To the other side is a tin bath, which Pentreath uses every evening when in residence, heating water in commercial-size steam kettles. “It’s very lovely,” he says.

When Pentreath wrote the book, he and McCormick were planning to add a third cottage to the site — similar in size but in corrugated iron — and to make the bothies their primary home. Things have changed radically since. The couple recently acquired a much grander Georgian house with a walled garden in the far north of Scotland and are now aiming to downsize in London and move there.

“We’re going really remote,” says Pentreath. “I think it’s going to take us longer to get to the bothies from our new house than it does from London, which is a bit mad. It’s extremely impractical, but we’re just not worrying about it. We’ve fallen in love with a house, and that’s that.”