December 4, 2017Artist Barnaby Barford works out of a studio in an industrial area of northeast London (portrait by Jane Looker). Top: He conceived his 2015 work Tower of Babel — which depicts in ceramic some 3,000 London storefronts — as a commentary on consumerism and the stratification of contemporary British society. Pieces of the tower are now exclusively on offer through the 1stdibs storefront of gallerist David Gill (photo by Thierry Bal).

A giant polar bear covered in meticulously crafted, white ceramic flowers towers benignly over Barnaby Barford’s cluttered studio on an industrial estate in northeast London. Porcelain figurines and smaller petal-strewn animals sit on shelves and windowsills, and computers, papers and paint-color charts jostle on trestle-table desks. Barford is a slightly unusual occupant here; his neighbors are a sash-window fabricator, a fish-and-chip-shop supplier and a maker of kebabs. “It’s a mix,” says the 40-year-old artist with a laugh.

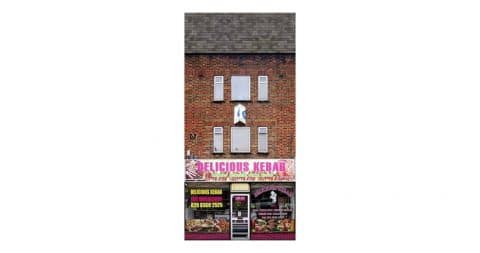

In fact, those neighbors might be the suppliers to some of the shops that Barford depicts in his ambitious and fantastical Tower of Babel, the project for which he is perhaps best-known. The tower, displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2015, is a 21-foot-high edifice comprising 3,000 tiny buildings made of bone china, each a faithful rendition of a real-life shop that Barford photographed during nine months of reconnaissance around London.

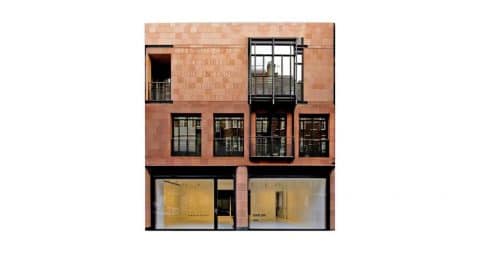

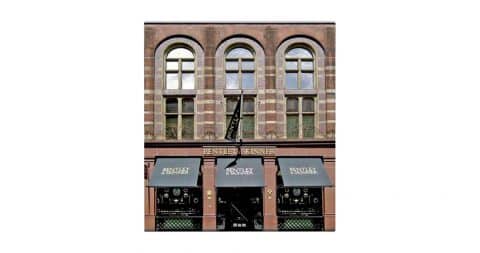

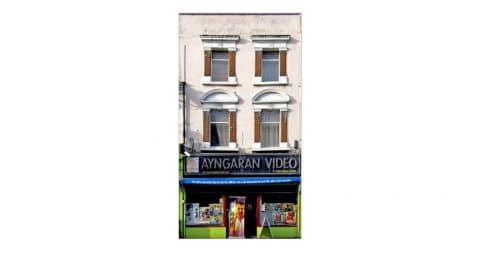

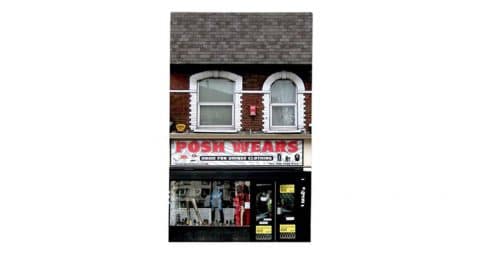

It’s an instant image of social aspiration and consumerism, starting with liquor stores, nail salons, chicken shops and derelict storefronts at the base and narrowing upward to a top-dollar crown of auction houses and blue-chip contemporary art galleries. Each tiny building is unique and for sale, Barford explains while opening boxes to show some that he still has. Around 2,500 pieces sold during the Victoria and Albert exhibition, and hundreds more are now exclusively available on the 1stdibs storefront of London gallerist David Gill, who represents Barford. The price, the artist notes, depends on the shop’s status in the pyramid, which means that a buyer must reconcile the desire to own a piece of the tower with how much he or she is willing, or able, to pay.

“Barnaby is always evolving as an artist,” says Gill, whose illustrious stable also includes David Chipperfield, Yves Klein and Gaetano Pesce. “I’ve been watching him since he was at the Royal College of Art, where I really noticed his imagination and creativity. I realized that his work in ceramics was not decorative but, in fact, sculptural. He always surprises me and, I think, his audience too.”

Rumpled, splattered with green paint and highly engaging on a chilly fall morning, Barford — who has recently added drawing and painting to his artistic oeuvre — spoke with Introspective about his consistent attraction to ceramics, his artistic preoccupation with the seven deadly sins and his questions about the role art can play in our society.

London’s Victoria and Albert Museum mounted an installation of the Tower of Babel in 2015. Photo by Thierry Bal

In much of his earlier work, including Dear Lord, for what we are about to receive make us truly thankful, 2007, Barford repurposed a variety of porcelain figurines. Photo courtesy of David Gill Gallery

Have you always wanted to be an artist?

I knew I liked drawing and making things, so after secondary school, I went to art college at the University of Plymouth. A key moment for me was when I went to Italy as an exchange student on the Erasmus program, which is a long-running European Union scheme. I ended up in Faenza, in Emilia-Romagna, which is an important ceramics center in Italy. I had already done a bit of ceramic work, and I had been attracted to it but had moved away from it, and this brought me back.

When I subsequently graduated from the Royal College of Art, I was using porcelain figurines, both antique and mass-produced, and chopping them up, painting them, sculpting them, to produce contemporary scenes in the style of [eighteenth-century British painter] William Hogarth.

If I look back on it now, that initial interest in ceramics was the same as it is now: It stemmed from the realization that you could repeat things, play with the industrial process. Whether it’s about taking thousands of objects to make a unique sculpture, like the Tower of Babel, or changing a single object to make it unique, it’s the same idea.

So, you went to the Royal College of Art in London after art college?

Yes, I felt like I needed something more, and at that point I was really exploring very different avenues: computer-aided design, prototyping and virtual art — things that aren’t actually physically made. The Royal College really opened me up to what was possible, and I started thinking more conceptually. I wanted to make work about us, our society, who we are as individuals with hopes and dreams and failures and frailties.

When I left the Royal College, in 2002, I made the decision that I would work full-time as an artist. It was really difficult financially for many years, but I decided I had to make work rather than try to support making work by doing something else to earn money. In 2004, I started working with David Gill, and it became a little easier.

In 2013, the artist created a series of mirrors based on the seven deadly sins. Wrath is seen here. Photo courtesy of David Gill Gallery

What kind of work were you doing then?

I was still making figurine sculptures, and I was always close to stopping, but something kept me preoccupied with them. At some point, I realized there were a few people doing similar work, and I thought, “I have to find a new path.” I knew I wanted to do something on the theme of the seven deadly sins, an idea that was around even before Pope Gregory wrote them down in the sixth century. I thought about whether they still matter, whether we care about these sins anymore. Are there consequences, and who polices them?

I ended up making large-scale mirrors, because I didn’t want to just make things — I wanted you, the person looking, to be implicated too. I decided I would use flowers, because they are the language of love, and love can take the forms of passion and obsession. So I made seven different mirrors using ceramic flowers treated in different ways, each reflecting a sin.

How did you make the flowers?

In the beginning, I made all the flowers by hand, from rolled-out clay, using cutters designed for baking. I squished each petal to be a little different, fired them, glazed them and fired them again. Some pieces were imprinted with different currencies made from decals, and that took another round of firing and glazing. Then, I twisted wire by hand and attached it to the back of each flower. The first piece, Avarice, had nine thousand flowers. It took about four and a half months to make.

Then I thought, “Crikey, I’ve got to do seven mirrors!” I started looking for fabricators. My wife, who is Italian, comes from a town famous for its tiles, and her father used to be a production manager in a tile factory. The technology of getting images onto ceramics is complicated, and this factory agreed to try the technique it used for tiles on the flowers. Luckily it worked, and I was able to keep going with the mirror pieces and then a number of commissions along the same lines.

For his 2016 exhibition at David Gill, “Me Want Now,” Barford made a series of large-scale animal sculptures, including The Baby Elephant, covering each with individual ceramic pieces. Photo courtesy of David Gill Gallery

How did the Tower of Babel come about?

While I was making the “Seven Deadly Sins” pieces, the most powerful and political element for me was envy. It was just after the 2011 London riots, which were down the road from this studio and really brought into contrast divisions within our capital city. I was thinking about how it starts with “Why can’t I have what they have?” And then it ends with “Why should they enjoy it if I can’t?” I wondered what triggers those feelings in our society.

Is it advertising? Is it the economic structure we live in, the political system? Is it the society that we live in, or does human nature lead us here? I got to the point where I asked, “Why do we shop, and why is our idea of aspiration and happiness so closely linked with consumption?” I wanted to ask, “Why has shopping become the great British pastime of choice, and how have we become so complicit in this?”

That is when I started looking at the actual shops. I was thinking about creating a city, and then I thought about the biblical tale of people who wanted to build a tower to make a name for themselves, and then God, feeling they were above themselves, dispersed them and made them speak different languages, so that they were unable to come together and achieve anything like this again. When you think about it in relation to London, people have come from all over the world, speaking hundreds of different languages, to set up shop here, creating a sort of tower of commerce.

When conceiving Tower of Babel, Barford explains, “I asked, ‘Why do we shop, and why is our idea of aspiration and happiness so closely linked with consumption?’ I wanted to ask why has shopping become the great British pastime of choice and how have we become so complicit in this.” Photo courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum

So, the Tower illustrates social inequality?

Originally, yes. It was a snapshot of London in 2014. I cycled more than one thousand miles around London, and I must have photographed around six thousand shops. I went to every part of London, its richest areas and its poorest. I really wanted, in a snapshot, to show the breadth of London life through the shops.

I hadn’t originally planned on selling the shops, but through discussions with the curator Alun Graves at the V and A, we came to the conclusion that since the whole thing is about consumerism, perhaps they should be for sale. This added a whole different dimension to the conceptual side of the project. The idea of the shops’ being different prices made you confront where you fit in the hierarchy of consumption. You might want Louis Vuitton, but maybe you can’t afford it. And each shop was unique, so two people couldn’t buy it, a bit like an actual real estate transaction.

“I cycled more than one thousand miles around London, and I must have photographed around six thousand shops,” Barford says, explaining his process in creating the Tower of Babel. “I went to every part of London, its richest areas and its poorest. I really wanted, in a snapshot, to show the breadth of London life through the shops.” Photo by Thierry Bal

What I found most interesting about the whole project was that once the work was finally installed, it became more than a critique of London’s rich-poor divide. It was, in equal measure, a real celebration of the city — of its rich history of trade and commerce, its independent traders, its architecture, its shopkeepers and its villages. On the one hand, the project was monumental, and on the other hand, it was really local. Sometimes people came to the museum because they heard their shop was there. Visitors would spend hours looking at the tower. I realized it brought a lot of joy to a lot of people.

What have you been working on recently?

For my 2016 exhibition, “Me Want Now,” I created large-scale word drawings, repeating the same word – like more – over and over. The pieces have a chaotic energy and immediacy that I think suggests the “me first” mentality that we live with. The repetition in those drawings is also in the large-scale animal sculptures in the exhibition: the polar bear, a wolf, a baby elephant, a deer, all covered with individual ceramic pieces. The predator and the prey exist side by side here.

We are living in a world where it can feel like we are no longer citizens, where we are just consumers, and we are dissatisfied and upset consumers. Then, you have the rise of right-wing rhetoric, poking at our deepest anxieties: The people who haven’t worked will come and take away what you have worked for. What role does art play in all this? Should I be taking a different, more communal approach to my work? I don’t really know where I’m going with this, but that’s quite exciting as well.