November 19, 2023Long before this past August, when the New York Times declared that we’re having a “cowboy moment,” the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver was busily putting together the show “Cowboy.” The truth is, we have never not been having a cowboy moment. The myth of the cowboy has been kicking around in the American imagination since the days of westward expansion. And it persists today as a problematic yet cherished fantasy of the laid-back, self-assured alpha male asserting his dominance over the land, the animals and everything else under the big open sky.

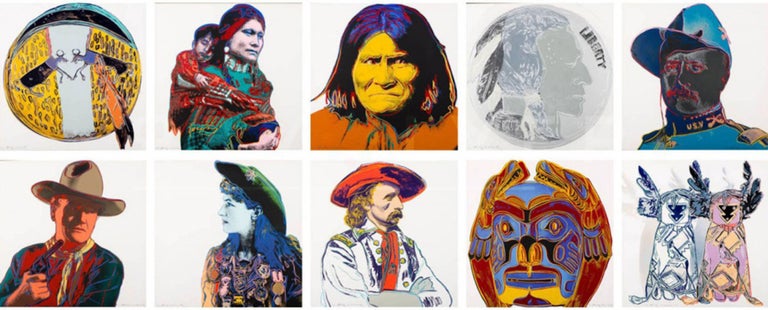

On view through February 2024, “Cowboy” shoots down the idea of the standard-issue straight white male figure depicted by Hollywood westerns and commercial advertising (in other words, the Marlboro Man, who is included here in one of Richard Prince’s appropriations).

“The show is part deconstruction and part homage,” says Nora Burnett Abrams, director of the MCA Denver, who co-organized the exhibition with Miranda Lash, the museum’s senior curator. “The cowboy looms large both as nostalgia and as an everyday experience here in the Mountain West.”

The show presents a wide variety of work by 27 artists from around the U.S. — including several from what might be considered cowboy country — encompassing painting, sculpture, photography and performance.

“I think a few people have come in with an assumption that this is a critique of traditional western art and are really surprised that that is not at all the experience of it,” Abrams says.

Some artists have taken the mythic Old West as a starting point, while others are focusing on lived experiences. “Some of them really lean into personalizing it, taking it from the register of myth or narrative and anchoring it as ‘This is my family, this is myself,’ ” says Lash.

That said, one thing is invariably at the center of the concept. “There are all kinds of cowboys,” Lash notes, “but it always kind of goes back to the horse,” which is why she and Abrams included a film still from Andy Warhol’s 1965 Horse, one of his takes on the western genre.

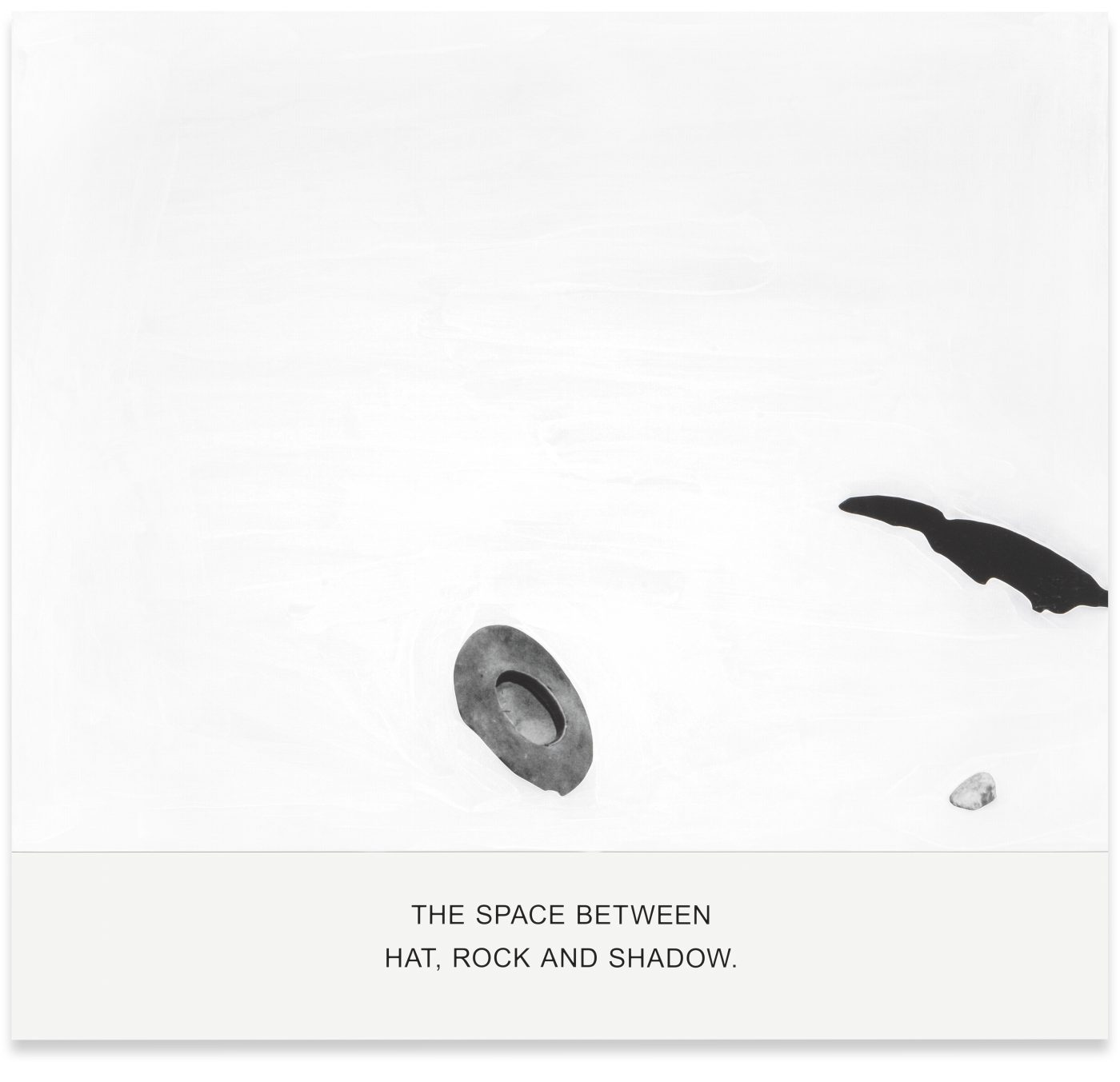

A 2019 work by John Baldessari, The Space Between Hat, Rock and Shadow, shows how easy it is to envision a typical tale of western grit from just a few basic cowboyish components — in this case a hat, a rock and a shadow, inkjet printed and varnished onto a white canvas.

It’s worth recognizing from the start that cowboys were never just white. In the post–Civil War period, when the cowboy character first started gaining steam, “of the nearly 35,000 cowboys who supported the ranching and cattle industry, over one-third of them were Black or Mexican,” writes Abrams in a fascinating historical overview of the archetype included in the extensive catalogue (published by Rizzoli).

As we can see from the work in the exhibition, whole swaths of people have authentically participated in the cattle herding, rodeos, horse riding and other labor and rituals that compose cowboy culture and yet don’t match the American fiction.

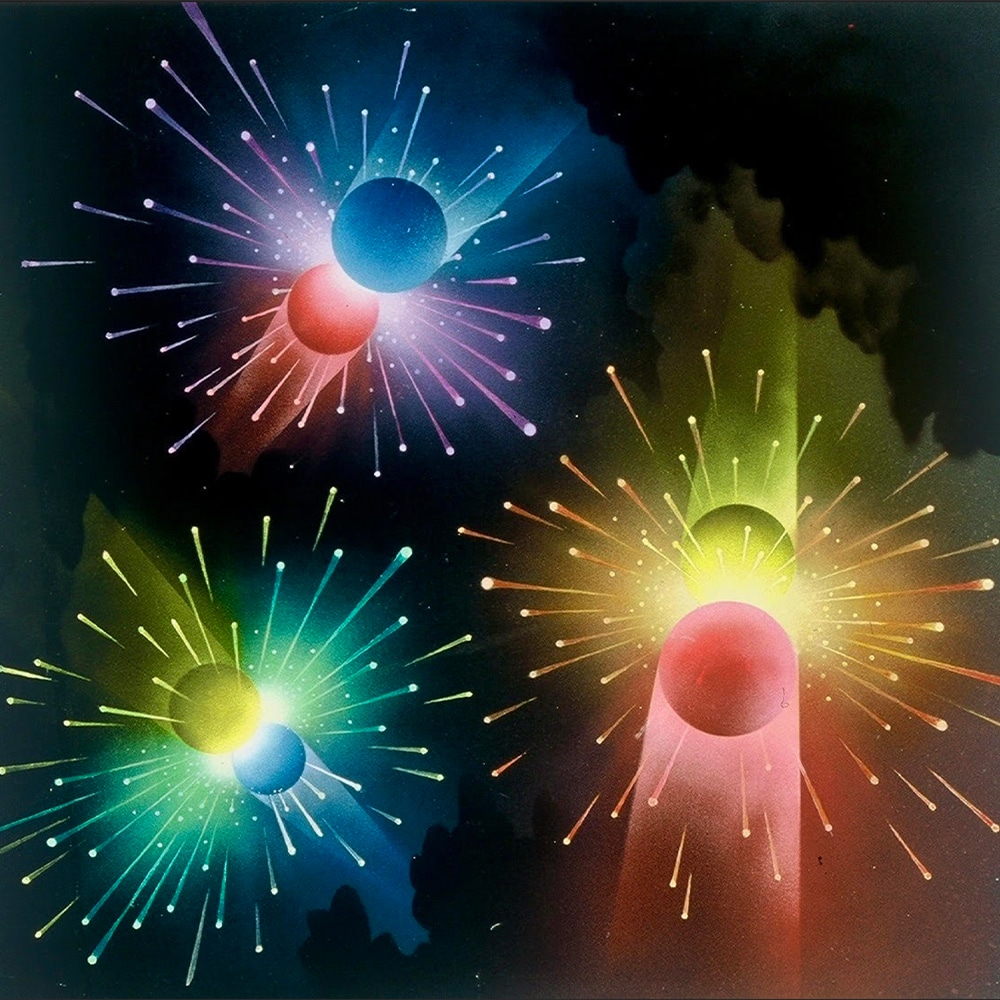

A drawing and sculpture from the 1970s by the Mexican-American Pop artist and social critic Luis Jiménez, who is celebrated for his massive fiberglass works, bring a colorful kitsch exuberance to images of life in the Southwest, from rodeos to steer wrangling.

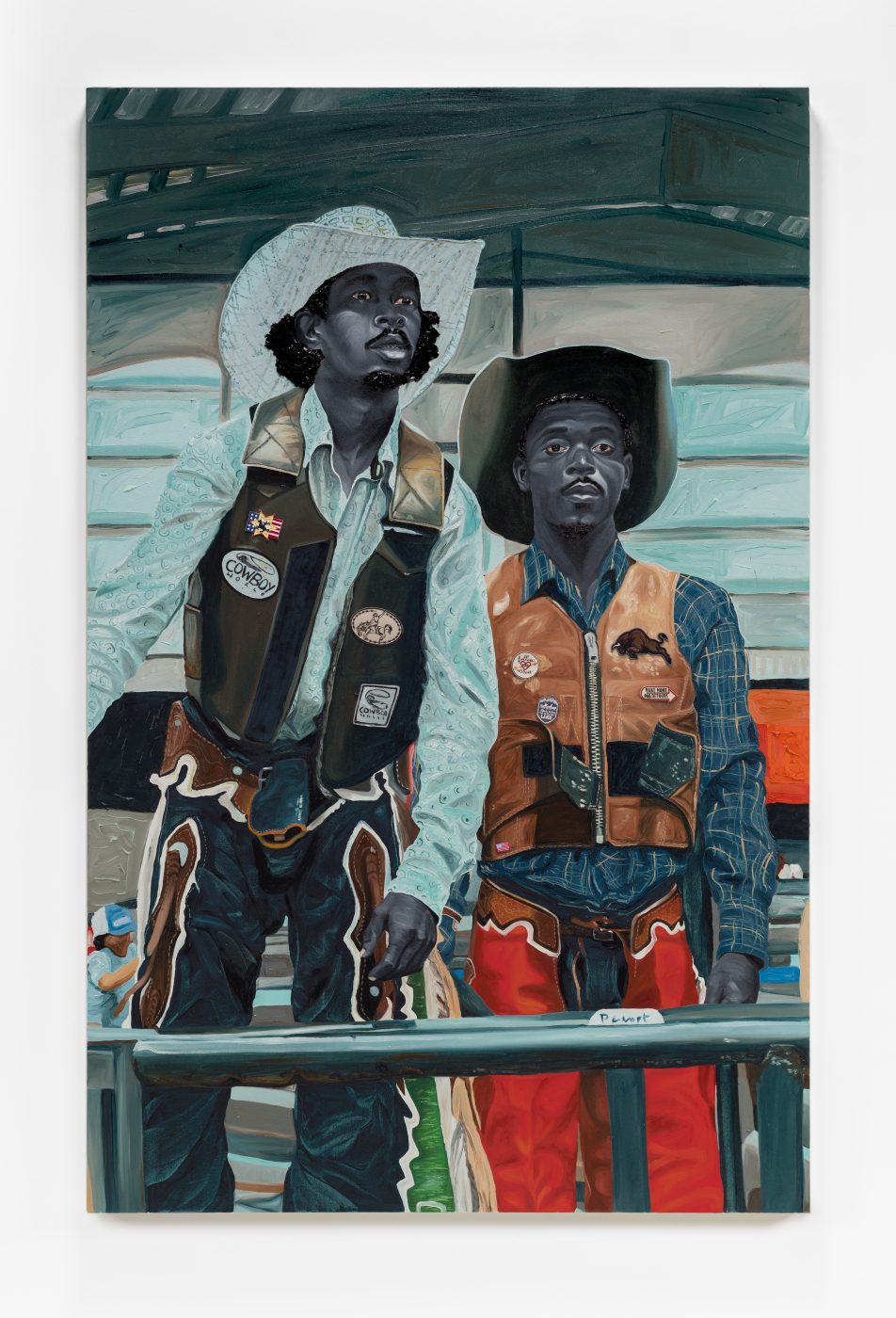

Portland, Oregon–based artist Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe grew up watching white-cowboy movies in Ghana, then later learned about Black cowboys. The show includes several portraits from his series of real Black rodeo participants, painstakingly rendered in oil with glitter and fabric appliqués.

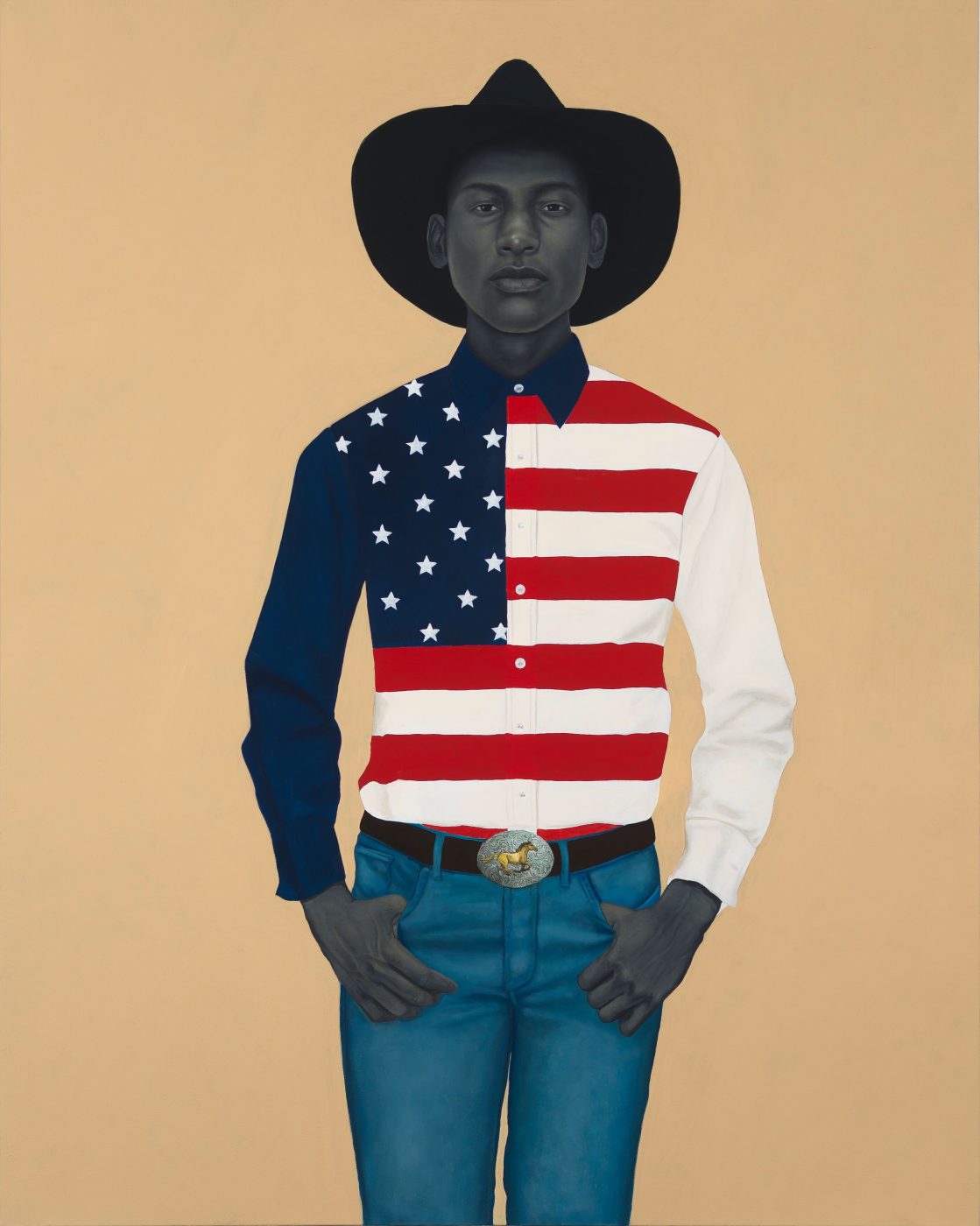

Amy Sherald and Deana Lawson both depict Black cowboys, but more as symbolic constructions. In Sherald’s case, her immaculate, unflinching subject wears an American-flag shirt, as if to reclaim the brand. Lawson’s shirtless cowboys, meanwhile, bring attention to Hollywood’s fetishization of rugged, sexualized Black riders as bandits.

A number of artists weave in the distinctly sexual terrain of the cowboy. Rafa Esparza speaks at length with Lash in the catalogue about growing up queer with Mexican immigrant parents in Los Angeles. For him, cowboy culture goes back to his family’s rural past and the labor of the vaqueros, or Mexican horsemen. He created a poignant site-specific installation centered on photos and paintings of Latinx men dancing in a queer bar, made in collaboration with photographer Fabian Guerrero. “When you see the piece, it’s so tender and intimate you want to cry,” says Lash.

For several of the women in the show, the Wild West is a menacing place. Colorado native Grace Kennison paints electrifying, violence-tinged paintings of female cowboys. And if you ever had any doubt, don’t call them cowgirls. “The term ‘female cowboys’ better gets at those who are working with animals, working the land, ranching. It feels more accurate,” says Abrams.

Angela Ellsworth’s Seer Bonnets are the ominous counterparts of the ubiquitous cowboy hat. Based on protective head garments that 19th-century Mormon pioneer women wore, they’re made of thousands of corsage pins arranged to form decorative patterns on the outside but lethally pointed inward to create a spiked lining that looks almost like fur.

Equally foreboding (and beautiful) is Mel Chin’s Rough Rider, 2002, a horse saddle he made by painstakingly manipulating barbed wire. Like many of the works in the show, it accomplishes a lot. “It’s an allusion to Buffalo Bill’s Congress of Rough Riders, but it also alludes to the Crown of Thorns and the Catholic history of colonization in Texas and the role of barbed wire enclosing the open range,” Abrams explains.

The fraught and widely fictionalized cowboy-Indian conflict surfaces in the work of two indigenous American artists. Oklahoma-based Nathan Young, who hails from the Delaware Tribe of Indians and is also related to the Pawnee Nation and Kiowa Tribe, tapped into his family’s long involvement with an Indian rodeo in Oklahoma. He asked relatives to lend him cherished keepsakes — belt buckles, cowboy boots, T-shirts, photographs, a saddle — which he then carefully arranged in a kind of celebratory site-specific display. “This work shows how invented and irrelevant the trope of cowboy versus Indian really is,” says Abrams. “There are many who identify as Native American or indigenous or tribal affiliating who practice cowboy rites and rituals.”

In a performance at the museum, multidisciplinary artist and activist Gregg Deal, a Pyramid Lake Paiute and punk rock musician, dons an elaborate costume with accoutrements like “Spam, certain herbs, beads for trading,” says Abrams. “The idea is to imagine a Native American figure who is engaging with the tools of the past but is not burdened by horrors of the past.”

Abrams is quick to make clear that the show does not dwell on the negative. “Even with Gregg Deal, the inside of his cloak has a punked-out John Wayne figure,” she says. “Artists are never so dogmatic as to say, ‘This happened, and we need to know this, and we can’t let it happen again.’ It’s more saying, ‘Hey, this happened, and it’s part of our collective history, and I’m inviting you to engage with it.’ ”