January 24, 2021If you think of a bag as just a receptacle for your necessities or as a frivolous seasonal fashion accessory, “Bags: Inside Out,” the capacious and stimulating new show at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, will make you think again.

By definition, a bag is indeed a container, but it does not always contain necessities. Neither is it always frivolous. It packs a lot of meaning. As the show’s curator, Lucia Salvi, notes during our chat at the exhibition, each bag is a comment on the utility of the invention, which is “common across all cultures and genders throughout the ages.”

Every bag also tells a story of ownership, and Salvi speaks of her long fascination with the “dual nature” of these objects, “their combination of private and public,” concealing our belongings even as they make bold statements to the outside world. “Bags: Inside Out” is an unprecedented look at a fashion accessory that today is not only a very personal possession but also a global obsession.

“The V&A holds more than two thousand bags from all over the world, and every department has them — Middle Eastern, Asian,” says Salvi, who mined the various collections for the show’s roughly 300 highly covetable designs, including many rare antiquities. “Sculpture has sculptures that hold bags. Paintings includes them. There are woven and embroidered bags in textiles.”

To bring order to this potentially overwhelming survey of social and cultural history viewed through the lens of bag design, she organized the exhibition around three themes: “Function,” “Status and Identity” and, finally, “Design and Making.”

Bags have been practical accessories since hunter-gatherers wandered the earth carrying foraged fruits and nuts in simple handmade pouches marked with a scratch or two to denote ownership. “Function,” however, opens in the 16th century, since bag design evolved notably during the later Middle Ages to meet the needs of increasingly prosperous, sophisticated and diverse societies.

As craftspeople grew in skill, and the choice of materials and dyes increased, the bags’ exteriors were embellished to please the eye and signify status, while the interiors held items that, it could be said, had become more intimate: clandestine love letters, treasonable missives inciting war, illicit drugs, to name a few. Societies hold secrets.

Among the highlights of “Function” is one of the rarest pieces in the exhibition, an exquisite 16th-century ruby-silk-velvet burse (square cloth case) densely embroidered with silver-gilt thread and beads. It is clearly significant despite its relatively small size, approximately seven inches square.

The bespoke piece was made to protect the silver matrix of Elizabeth I’s Great Seal of England. (Matrices were used to create wax-seal impressions on such political documents as royal proclamations.) Next to it is displayed an exquisite circa 1588 miniature by Nicholas Hilliard depicting Sir Christopher Hatton, a possible user of this burse, holding a similar one.

In this period, men proudly proclaimed their wealth with coin pouches hanging from their belts, while women carried their possessions, scented and secreted, in the folds of their voluminous skirts. Tie-on pockets were accessed through slits in the seams. On display is a fantastic life-size dress form wearing a cutaway gown revealing these inner sanctums.

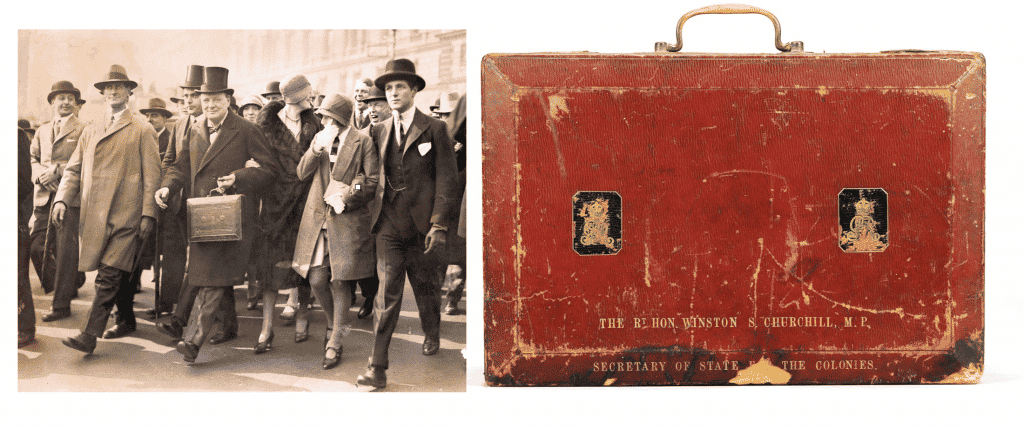

Pockets eventually became integral to garment design, but bigger sacks were needed to carry books and documents. What state secrets were carried within Winston Churchill’s dispatch box, made by John Peck & Son in 1921? The battered red leather exterior belies the box’s political gravitas.

Transatlantic travel by the wealthy, which burgeoned at the cusp of the 19th and 20th centuries, necessitated even larger cases. On view is a circa 1900 Malle Haute trunk by Louis Vuitton. It’s a design we still see today, a reminder that well-made is well worth an investment.

Fashion labels, or brands, grow in importance from the mid-20th century onward as fashion becomes a global business that fuels conspicuous consumption. The central section of the exhibition, “Status and Identity,” is packed with bags of all sizes and shapes, for every occasion, that evoke politics and power, celebrity and status.

All of these are conveyed by the handbag made for UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher by Launer, the exclusive purse purveyor to Queen Elizabeth II. Thatcher was hardly considered a fashion influencer, but that drab bag symbolized power and achievement. Plus, it was a weapon — she famously used it to whack an irritating constituent.

Salvi calls particular attention to actress Jane Birkin’s very own Hermès Birkin, the first bag to be named at origin after a celebrity. It has the well-worn exterior of a much-used and much-beloved possession. Birkin’s usual overflowing in-flight travel basket was noticed by the man sitting beside her, Jean-Louis Dumas, then chief executive of Hermès. By the time they landed in Paris, it seems, they had designed a large, functional leather bag with pockets.

The first one hit an unsuspecting market in 1984. It’s doubtful Hermès could have predicted the phenomenon it became. But the ’80s were a gilded age, in which women climbed the corporate ladder in droves. Making money was gender-neutral. And a Birkin was practical, for those business papers, as well as au courant. It was the fashion accessory of the century because of the status it bestowed. Even in informal contexts, women were secure enough to wear faded Levi’s with a crisp white Gap T, as long as they carried a Birkin.

Featured in HBO’s late-’90s series Sex in the City, the bag became a celebrity in its own right, with a waiting list — something savvy reality-show stars like Kim Kardashian West picked up on. Probably empty, the ones Kardashian West carries help her to play a part: “I carry a Birkin, therefore I am.” Everyone who is anyone today has whole rooms full of them, and anyone who is no one makes do.

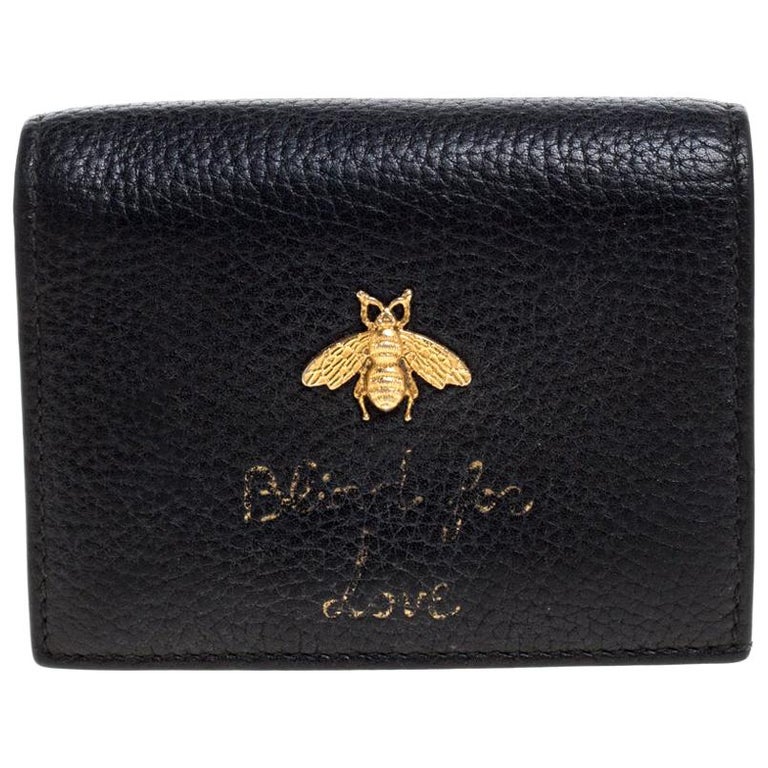

Today, fashion-conscious consumers generally know which bag denotes what and, when in doubt, buy top of the market. Most of those high-end pieces are included in the exhibition. A black leather Hermès Kelly is cool like its blonde namesake, Princess Grace. A quilted Chanel is a classic; it never fails. Influencer Alexa Chung’s Alexa bag, made by Mulberry, is a savvy nod to the exhibition’s sponsor. Supreme, Off-White, Gucci, Miyake, Vuitton, Versace, Loewe — oy vey! Contents are irrelevant.

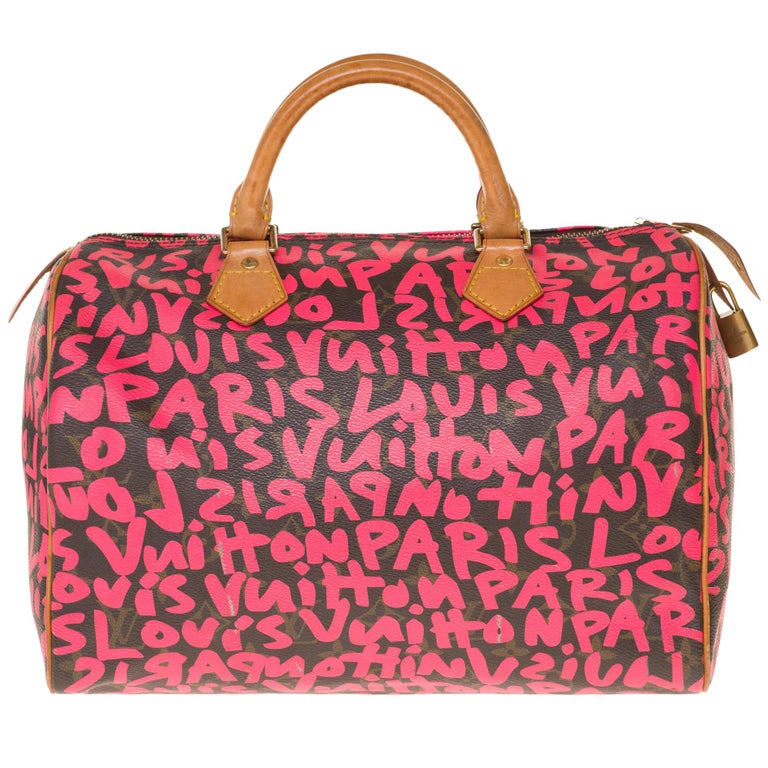

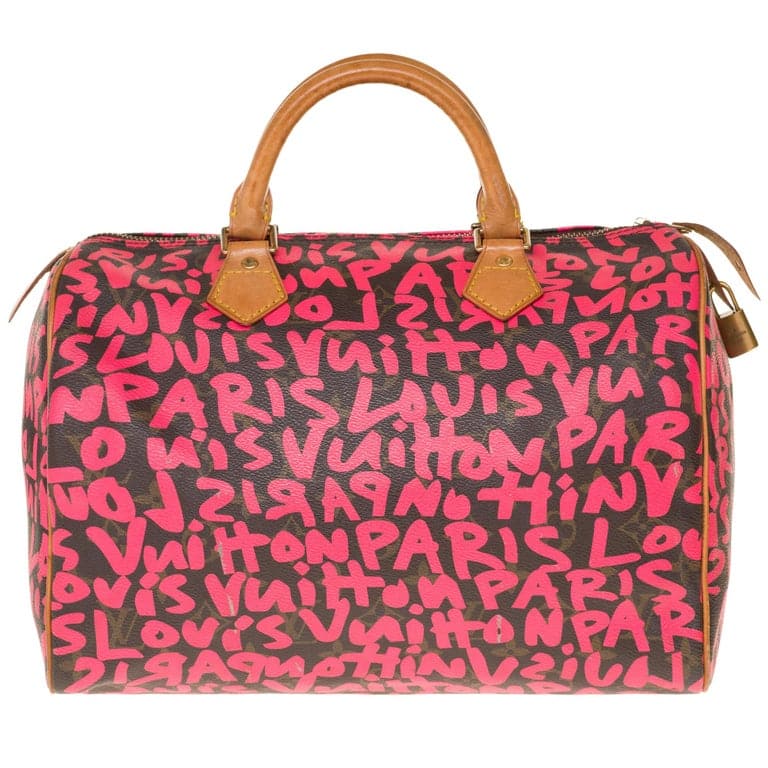

Along with the times, bag design is a-changing. The final vitrines of “Status and Identity” feature politicized examples. Here, the exterior acts as an artist’s canvas to carry a literal message. As far as fashion big business is concerned, this trend originated in 2001, when designer Marc Jacobs collaborated with downtown NYC artist and designer Stephen Sprouse to rework Louis Vuitton’s traditional monogram into a graffiti scrawl. The move rejuvenated both men’s careers — and revived the flagging traditional brand, realizing $300 million in sales. Collaboration became the name of the game.

More radically, the new century brought millennial awareness of the plight of the planet — dwindling natural resources, the impending extinction of innumerable species, rampant pollution and racial and gender inequality and intolerance. Bag design in the 21st century tends toward simple silhouettes like totes, and the exterior statements can be literal slogans. The duality of bag design is more conceptual. Contents are ancillary to the message.

Salvi points to a cotton-candy-pink plastic bag. “The first plastic bag in the museum’s holdings!” she proclaims. “Anthropological artist Jeremy Deller showed it at Frieze Art Fair in 2003.” She grins, as well she might, for stamped on it in black uppercase letters is “Speak to the earth and it will show you,” a timely subversion of a Biblical instruction from Job: “Or speak to the earth, and it will teach you.” I will never ever use another plastic bag.

At the opposite end of the display is a Birkin-like design in natural-cotton canvas created by New Yorker Mary Ping for her label Slow and Steady Wins the Race, a part of her 2003 conceptual collection of “It” bags. Just to shake us up, in case we weren’t already shaken, between the two is an astonishing small, well-used, once-ivory silk bag. It is an antislavery reticule — designed in 1825 by English painter Samuel Lines and featuring a print by him on the front — which was made by the Female Society for Birmingham to contain political pamphlets and convey their beliefs to the general public. “No such thing as original, right?” Salvi says, smiling.

The final theme, “Design and Making,” examines the process of producing a bag from sketch to selling, including ancient techniques still used today. Metalwork is exemplified by a 1960s Paco Rabanne belt bag next to a 17th-century purse. Experimental and innovative forms and materials are on view. Function is maintained, but exteriors are subverted.

A divine, tiny, intricately beaded frog of silk and metal from the 1600s evokes a Judith Leiber design. Salvi conjectures it could have been used as a “sweet bag” to carry herbs and scents. Fashion designer Thom Browne pays homage to his dachshund, Hector, with a very well-dressed sausage-shaped bag. Artist Tracey Emin’s International Woman bag, a limited-edition wool-appliqué suitcase for Longchamp, has no other function than to make us think of romance and travel. Stella McCartney’s sustainable backpack made from recycled ocean plastic is one of a number of items that welcome the future.

The dual nature of a single bag becomes a multisensory experience when viewing 300 or so spanning the world and more than five centuries. As the V&A makes clear, the bag is not merely a piece of fashion frippery. It is an iconic part of the history of design that holds a unique place in our lives.