May 2, 2021When white LED lighting first emerged widely on the consumer market about a decade ago, it came in a recognizable form: the screw-fixture light bulb. That seemed odd to Esther Jongsma and Sam van Gurp, then students at the Netherlands’ prestigious Design Academy Eindhoven.

“The light bulbs we were using had to be protected, because they are very fragile,” Jongsma says. “So of course it made sense to have the filament encased in glass.” But LED lights heat up quickly, “so it’s not at all logical to have it covered in glass, which just makes it hotter.”

LED lighting also has the virtue of being far more flexible than incandescents or fluorescents, so why, the designers wondered, was it stuck in the same form as a bulb that was used in the most traditional of lighting fixtures?

It was natural for both Jongsma and van Gurp to think a lot about light as young people growing up in the Netherlands, where the sky is constantly changing. Illumination and shadow and the contrast of black and white, or chiaroscuro, has been a central theme of the country’s art and design since the Golden Age of Dutch painting in the 17th century.

“For us, LED light was a field of design that needed to be discovered,” Jongsma explains. “Sam was thinking about light and the sun and how its light is always ‘on.’ It’s the movement of the Earth that makes it go on and off — the sun doesn’t go off.”

For their first collaboration, completed while they were still in school, van Gurp and Jongsma developed Exploded View, a lamp whose LED module can be moved up and down, in and out of its shade, on wires, by means of a clever weighted pulley system. As the module rises and falls, it illuminates the surrounding space in different ways, creating various atmospheric effects. Microsoft became an early client, buying the lamp for its Seattle headquarters.

Following their graduation, Jongsma and van Gurp spent a few years working in their separate studios; she focused on furniture design while he concentrated on lighting. In 2015, they merged to form VANTOT, which in Dutch means “from to.” They chose the name because it expresses the process of working on a design project from conception to production.

The duo — who are partners in life as well as in design and have an infant daughter named Fé — based VANTOT in Sectie-C, a former factory site in the Tongelre district of Eindhoven. A creative hub for emerging makers and start-ups, it is also the center of the city’s famous Dutch Design Week, held every October. The area made an apt setting for their work, since lampposts, switchboards and illuminated traffic signs had previously been manufactured there.

The first official product of their new company, 2015’s Limpid Light collection, was another exploration of how the quality of illumination can change as an LED element moves in and out of its shade. As with Exploded View, the duo created a counterweighted pulley system that moves the light in and out, up and down. Artisans in the Czech Republic make the series’ handblown glass shades in clear or smoky finishes to which Jongsma and van Gurp add color. To do so, they use what Jongsma calls “a secret recipe that doesn’t involve paint,” creating shades such as bronzite, tanzanite blue and graphite.

Although they have a fleet of major clients (including Twitter, Crown Hotels and Marriott) and export far and wide (to the United States, Australia and the United Arab Emirates), they have no gallery or showroom. Instead, they conduct all operations from their 3,200-square-foot studio, attending art and design fairs and selling through their 1stDibs storefront. A concrete and steel industrial space with 20-foot-high ceilings, their studio is a kind of lighting laboratory in which they experiment with new inventions.

The studio contains a metal workshop, a sandblasting machine, a thermoforming machine and a 3D printer. They work for months on prototypes of their latest lamps, testing them and perfecting the materials as well as their inimitable style, which combines aspects of 1920s Art Deco and chrome-and-brass 1970s glam, with a futuristic twist.

The couple’s deliberate process ultimately produces a new line only once every two years. A collection always “starts with our own fascinations,” says Jongsma. “Inspiration can be in the smallest things. We walk a lot in the forest near our studio, and we look at reflections in the water, for example, or if it’s a foggy day, we observe how light is diffused near the ground. It’s mostly the changing light from day to day that gives us inspiration.”

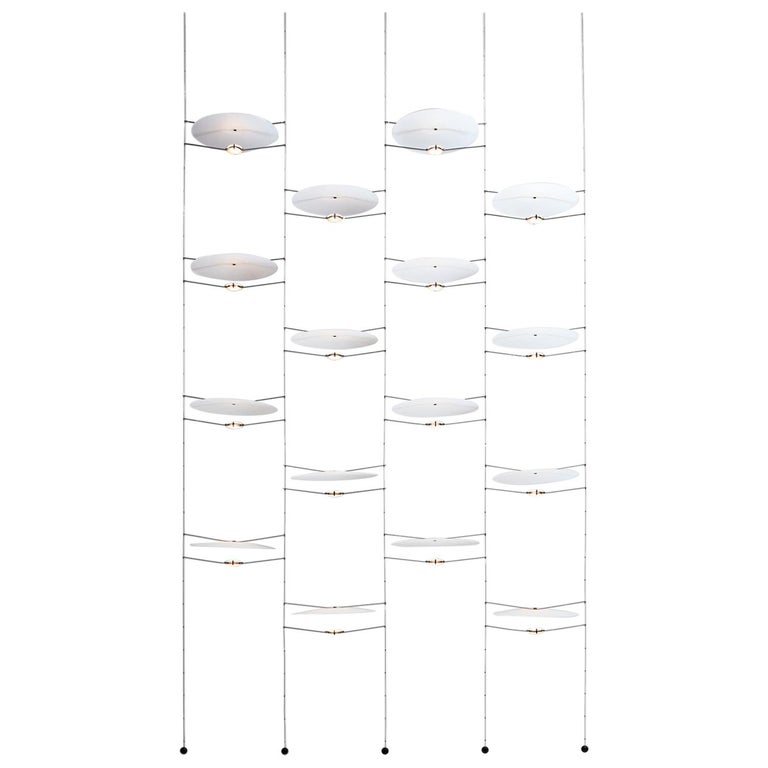

Each piece in a collection can be reproduced in unlimited editions, but they also create lamps that are “more like art pieces,” made in editions of no more than five. They also sometimes work on commission, creating unique lighting for a client to fit a particular location. For Eindhoven’s Victoria Park, for example, they designed motion-sensitive solar lamps they call Sunseekers. Each of the installation’s disk-shaped elements looks like a cross between a UFO and an umbrella, and they’re all supported by pairs of wires suspended between tall poles, high above the park’s walkways.

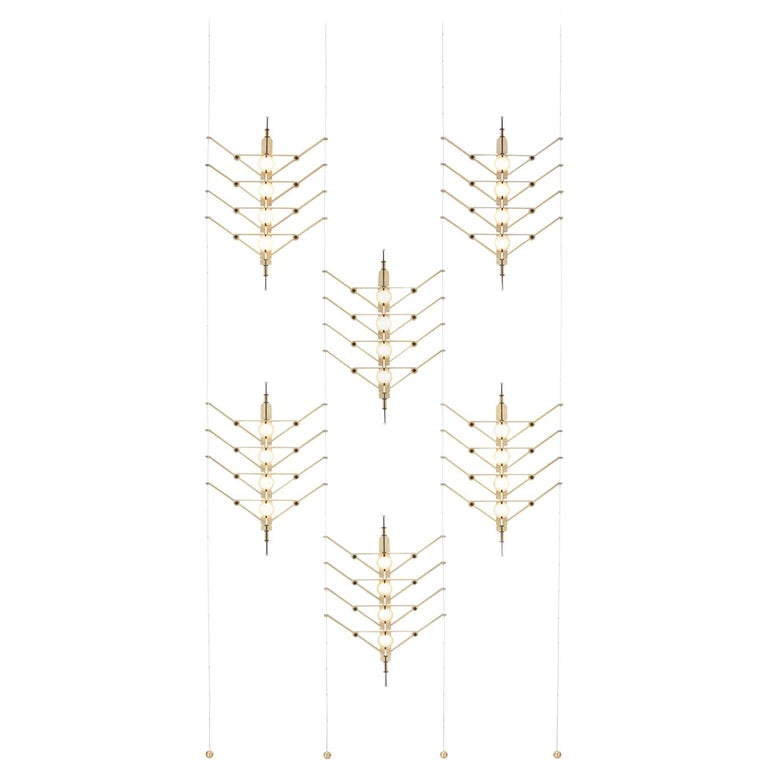

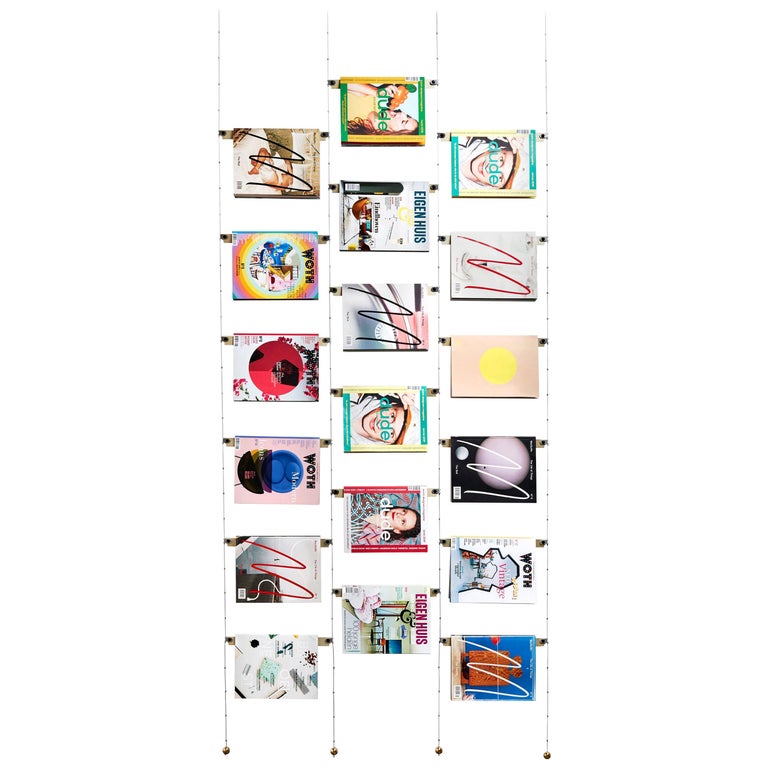

Two other collections, the V-V-V series and the O-O-O series, take advantage of LEDs’ versatility to create a modular curtain of lights. Both collections connect ornate lighting elements with a lattice of stainless-steel cables. The V-V-V series features lights fixed onto an Art Deco–style anodized aluminum frame while the O-O-O has spaceship-shaped light. Both can be used as partitions for large spaces, to screen one area from another or as decorative design elements set against a wall.

By connecting the LEDs through the stainless-steel lattice, VANTOT was able to almost eliminate the use of electrical cables, says Jongsma. “It’s like one big electrical circuit,” she says. “For us, it was really a moment of complete liberation. Everything you see transports the energy.”

Having been named Emerging Designers of the Year by Dezeen in 2020, they are looking toward a future in which they can also create lighting systems that are entirely free of cords. In addition to solar energy, they’re thinking about generating light from sources of kinetic energy, such as the opening and closing of a door or a person’s movement in a room. Jongsma says she’s curious to find out if window curtains might be able to collect and store energy indoors.

“We’d like to, at some point, create a light that doesn’t need to plug into an electric outlet,” says Jongsma. “It would be more of a stand-alone system, a lamp that might be harvesting light during the day and using it in the evening. We believe lighting will be way more dynamic in the future.”

TALKING POINTS

Esther Jongsma shares her thoughts on a few choice pieces