February 23, 2020In a textile mill in Northern Italy, the hooks and knives of a jacquard loom chugged up and down, merging mauve, salmon, light gray and pale green yarns into one trippy geometric fabric, while an international cadre of design reporters took photos and videos of the loom’s actions. This cloth will soon cover the wide, floppy cushions of a Vlinder sofa, designed by Hella Jongerius for Vitra.

Nearby, in a rustic plaster-walled and timber-ceilinged reception hall, a completed Vlinder sofa held court with a few of Jongerius’s Bovist poufs clad in similarly inventive textiles, tempting the reporters to try them out. On the opposite wall hung a tapestry-size swath of the Vlinder fabric, along which the guests could run their fingers to experience the variations of texture, which ranges from smooth to raised, soft to scratchy.

Hella Jongerius sorts through fabrics in her Jongeriuslab workshop in Berlin (photo by Roel van Tour). Top: The Dutch designer’s Vlinder sofa holds court with her Bovist poufs in the 15th-century Palazzo Terzi, in Bergamo, Italy (photo courtesy of Vitra).

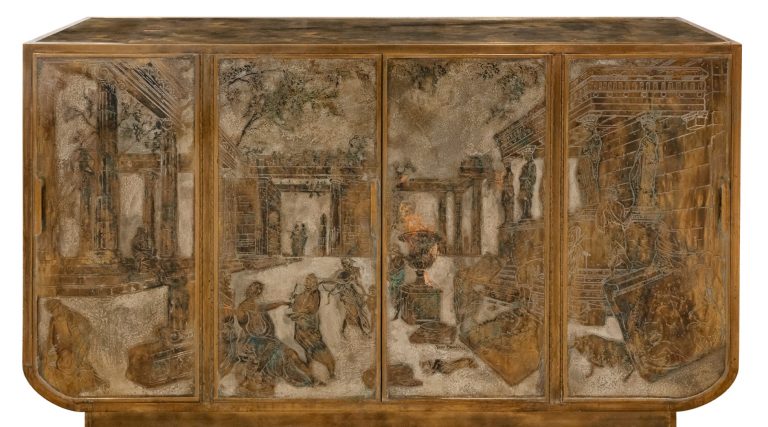

The Vlinder and Bovists made other appearances during the press trip. They showed up on a tour of a young count’s 15th-century palazzo in Bergamo and finally in the homey Herzog & de Meuron–designed showrooms of VitraHaus, on the Swiss furniture company’s campus in Weil am Rhein, Germany. And so, watching the Vlinder’s fabric being made in Italy was like seeing a celebrity naked — familiar and confusing at the same time.

It’s like no other upholstery you’ve ever seen or felt, with an unpredictable variation of patterns and surfaces that Jongerius has coaxed out of eight different yarns. The Vlinder is the Dutch designer’s first sofa since 2005, when she launched the boldly hued, asymmetrically cushioned Polder sofa, also for Vitra, where she serves as director of the Colour and Material Library.

Although she’s largely known as a product designer for companies ranging from Droog to IKEA, the Dutch-born Jongerius, one of the many stars to emerge from the Design Academy Eindhoven, has been creating fabrics for Maharam for nearly two decades and has recently explored the performance-art side of weaving. In 2019’s Space Loom, she conceived an epic, four-story-high installation of multicolored warp yarns with weavers in the center working them into three-dimensional shapes. Space Loom was such a hit when it was exhibited in the show “Interlace” at the nonprofit art space Lafayette Anticipations, in Paris, that the Centre Pompidou bought the piece for its collection.

Back at his desk in New York, Introspective executive editor Trent Morse caught up by phone with Jongerius, speaking from her Jongeriuslab studio, in Berlin, where she was preparing for her next museum show. Below, she talks about color, tactility and the sillier side of Dutch design.

1. In creating the Vlinder, what were your inspirations and influences for the fabric and the shape?

I was asked eight to ten years ago to make a new sofa, but I didn’t have a good idea of what it would be. At first, I wanted to do something with flowers, but the geometric pattern fits better to the sofa. The pattern is asymmetrical because the sofa itself had to be symmetrical.

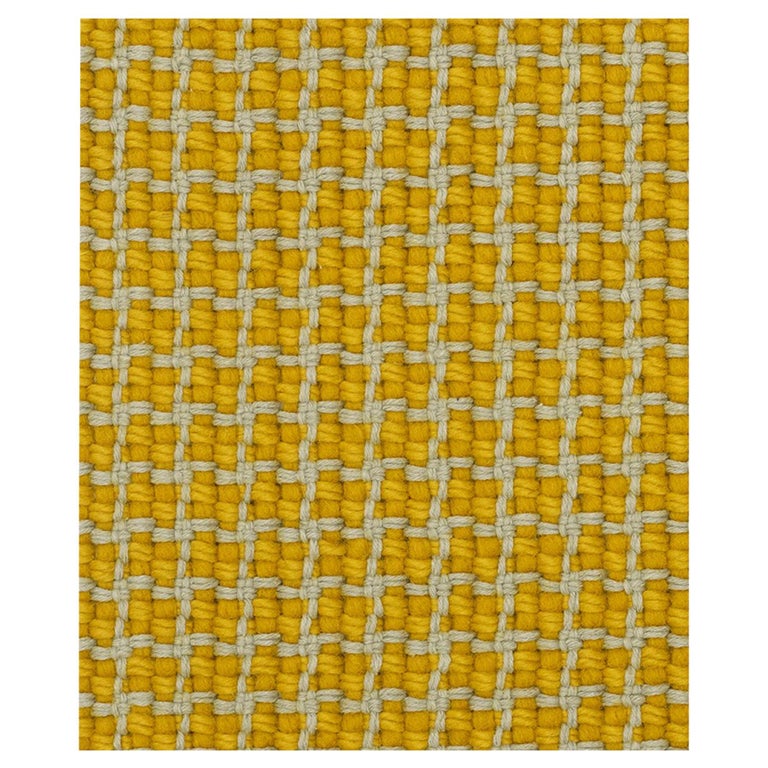

The sofa is about the cover, the skin. I started with the weaving, and the shape followed the pattern. All looms can do these kinds of special textures, but I wanted to push modern weaving technology by creating a pattern made up of samples. I used eight colors of yarns in two thicknesses to create four color collages in seven different jacquard weaves. It’s a highly engineered textile.

A weaver constructs 3-D forms out of warp yarns as part of Jongerius’s performative Space Loom installation at Lafayette Anticipations, in Paris. Photo by Roel van Tour

2. How did you decide on the color combinations?

With the Vitra Colour Library, where I am director, I always start with greens and reds, lights and darks. I use these as the compass for all the textiles, chair colors and leathers. That’s the way I delve into the library, and it’s how I picked the colors for the Vlinder, as well.

You try a lot of different color combinations, so it’s like a puzzle, where you’re piecing together the darks and the lights, the reds the greens. It’s a collage of samples, a modern quilt of different islands of pattern and texture. That’s why we called it Vlinder — which means “butterfly” in Dutch — because everyone sees something different.

3. How did you get into weaving and textile arts? Were you around these crafts as a child in De Meern, the Netherlands? How did you transition from designing hard furniture to softer fabric works?

I grew up in the eighties, and as a girl, I did a lot of knitting and stitching. My mother was a patternmaker, and she was always sewing our clothes.

In the year 1999 or 2000, I was asked to work for Maharam, and I’ve been creating five fabric patterns a year for them. A few years after I started with Maharam, I was asked to make the Polder sofa for Vitra. With the Polder, I used six different types of textiles.

With the Space Loom last year in Paris, I wanted to be more free by making a giant loom with an inner circle of weavers.

The Vlinder sofa and Bovist pouf in the Italian textile mill where their upholsteries are woven. Photo courtesy of Vitra

4. Tell us about your time at Droog, the Dutch design collective.

I was with Droog at the beginning of my career for eight years. I created rubber vases and the B-Set ceramics, which were about using imperfection and originality within the industrial production. Each cup came out differently because of how hot the kiln was. So you could say the topic of imperfection was there from the very start. I’ve long been interested in how to use craft and the hands in manufacturing. I’m always searching for ways to inject oxygen into industrial products.

Jongerius with a fabric panel for the Vlinder. Photo by Roel van Tour

5. Why do you suppose the Netherlands has produced so much figurative, humorous, oddball design: Droog, Marcel Wanders, Studio Job? Is there a lot of humor in the culture?

It is hard to say what is Dutch about humor. There was a moment when storytelling came about in design in the 1990s. I left Droog around that particular time, and then the market took over and everything became about storytelling.

I don’t have a lot of jokes in my work. I’m more focused on material and production. In the marketing of commercial textiles, there aren’t a lot of words to describe material, texture and form. It’s all about value.

I have two daughters, fifteen and seventeen. They are, happily, not interested in design. My girls are always on their phones. That’s why weaving is important to us all — it makes you feel alive to touch fabric, where tactility is absent in the digital world. In the real world, it’s important to get to know and be aware of pattern and texture. Textile is the one material that gives you this tactility.

Now, I have the textile library at Vitra, so I’m looking at weaving from a cultural-historical point of view. Weaving is not just a technique, it’s a worldwide historical phenomenon. Every culture has a different loom and different skills. We are all interwoven.