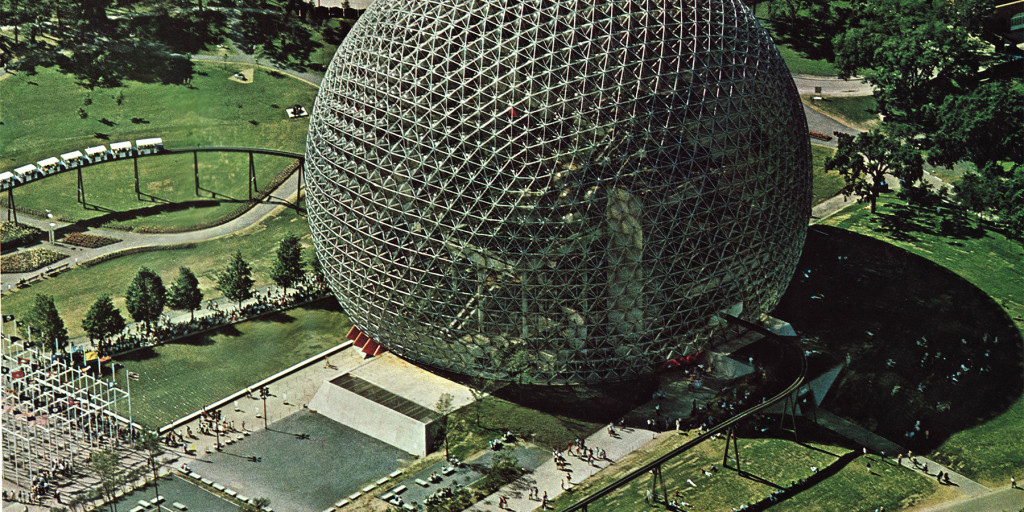

April 18, 2016An interior view of the United States pavilion — a Buckminster Fuller–designed geodesic dome — at Expo 67 in Montreal, one of numerous international exhibitions meant to foster cultural diplomacy during the Cold War that are explored in “Make-Believe America,” at the Museum of Design Atlanta. Top: The 200-foot-tall acrylic-and-steel structure incorporated a monorail and the longest escalator ever built at the time. All photos courtesy of the Museum of Design Atlanta

When is a chair more than a chair? When it becomes a physical embodiment of political and cultural ideas. If you ever wonder why design of the mid-20th century is enduringly popular or why creators like Charles and Ray Eames, George Nelson, Buckminster Fuller and Ivan Chermayeff are legendary, here’s a reason: They were visionaries who forever changed the way we view furnishings and architecture. From the Eameses’ molded-fiberglass chairs to Fuller’s geodesic domes to Chermayeff’s groundbreaking graphics, these designers pioneered the look and feel of a new, more mobile, faster-paced postwar world.

As is made clear in the new show “Make-Believe America: U.S. Cultural Exhibitions in the Cold War,” at the Museum of Design Atlanta (MODA) through June 12, they were also adept at creating an optimistic (and occasionally sensationalistic) vision of America. That vision was promoted all over the globe, at world’s fairs, trade shows and museum exhibitions, in a campaign meant to curb the influence of communist ideology and propagate the American dream.

“Design can be a powerful political tool,” says Laura Flusche, MODA’s executive director. “We wanted to showcase the great latitude mid-century designers were given in creating a national image for the U.S., which isn’t a role we commonly think of them playing.”

Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev (left) and U.S. vice president Richard Nixon in the kitchen of a model home created for the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow.

From 1955 to 1975, when these international expositions proliferated, top-notch designers from the United States masterminded pavilions, displays, films and graphics to demonstrate the superiority and prosperity of the American way of life, with only the loosest government oversight.

“These guys were at the top of their game. There was nothing they couldn’t design,” says Andrew J. Wulf, executive director of the New Mexico History Museum, who curated “Make-Believe America.” Wulf incubated the idea for the exhibition as a museum-studies PhD candidate at the University of Leicester, in England, and as a fellow at the University of Southern California’s Center on Public Diplomacy. Casting about for a thesis topic, he became interested in how international expositions were used to win hearts and minds in the Cold War era. “My dissertation is basically what you see on display at MODA,” he says.

In 2009, Wulf was introduced to Jack Masey, who died last month at the age of 91. As a Yale design grad and writer for Architectural Forum, Masey was recruited in the early 1950s to join the newly formed United States Information Agency (USIA), the cultural-diplomacy arm of the federal government, created by President Eisenhower. Masey’s personal collection of artifacts, photographs, graphics and original film footage became the centerpiece of the exhibit, and his testimony about the genesis of these formative pavilions served as what Wulf calls “the straight story.”

The American Atomics Pavilion, designed by architect John Vassos for the India World Exhibition, held in New Delhi in 1955.

The government administrators tasked with creating cultural exhibitions in far-off places, Wulf explains, “had no idea how to proceed.” So they hired Masey and gave him a shoestring budget, first for the 1955 Indian Industries Fair in New Delhi, for which he called on industrial designer John Vassos to build an atomic-themed U.S. pavilion, and then, one year later, for the Jeshyn International Fair in Kabul, Afghanistan. “With very little time and money to build a brick-and-mortar installation,” says Wulf, “Masey contacted one of his idols, Buckminster Fuller, and said, ‘Can you design me one of your incredible geodesic domes?’ And Fuller said, ‘Absolutely!’ It was the hit of the fair.”

Masey, says Wulf, quickly learned that “the way to make a splash and a successful event was to hand it over to the designers carte blanche.” He hired the best designers he could find, like the Eameses, who projected their film Glimpses of the USA onto seven 20-by-30-foot screens suspended within another Fuller geodesic dome for the 1959 U.S. National Exhibition in Moscow. “It was an influential first foray into the fast-moving, image-saturated world we inhabit today,” Flusche says, “and it had great influence on advertising and other media.”

A model kitchen meant to illustrate the futuristic capabilities of the modern American home sparked the famous Kitchen Debate between Khrushchev and Nixon during the American National Exhibition in Moscow.

Of the hundreds of fairs America participated in during this period, “Make-Believe America” zeroes in on a select few. The 1959 Moscow exhibition is considered by Wulf to have been “the Rose Bowl” of these expos, featuring a full suburban-style split-level house with a state-of-the-art model kitchen and a real-life housewife baking cakes from Betty Crocker mixes. It also happened to be the site of the historic Kitchen Debate, where U.S. vice president Richard Nixon and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev engaged in vigorous one-upmanship about capitalism versus communism.

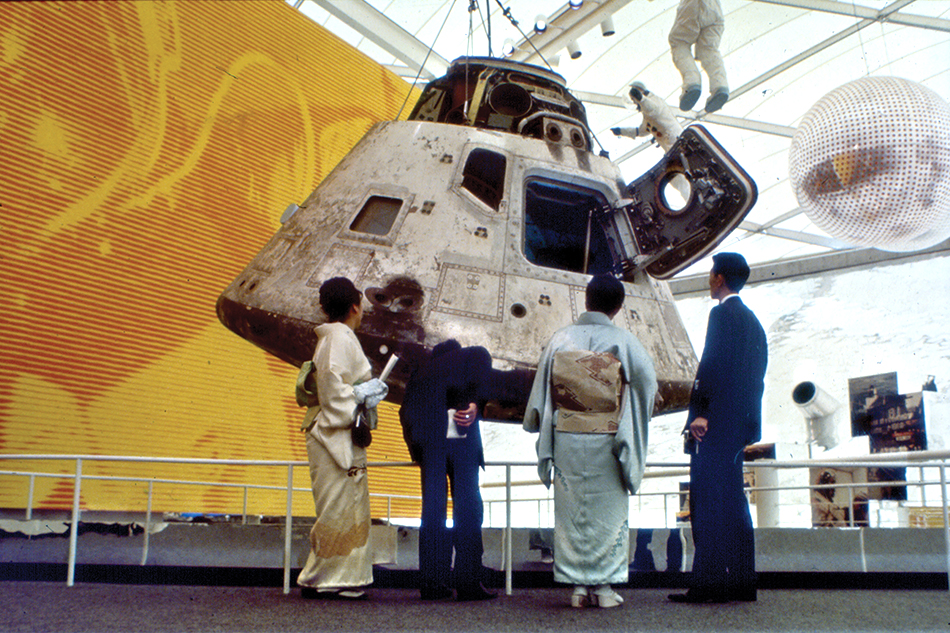

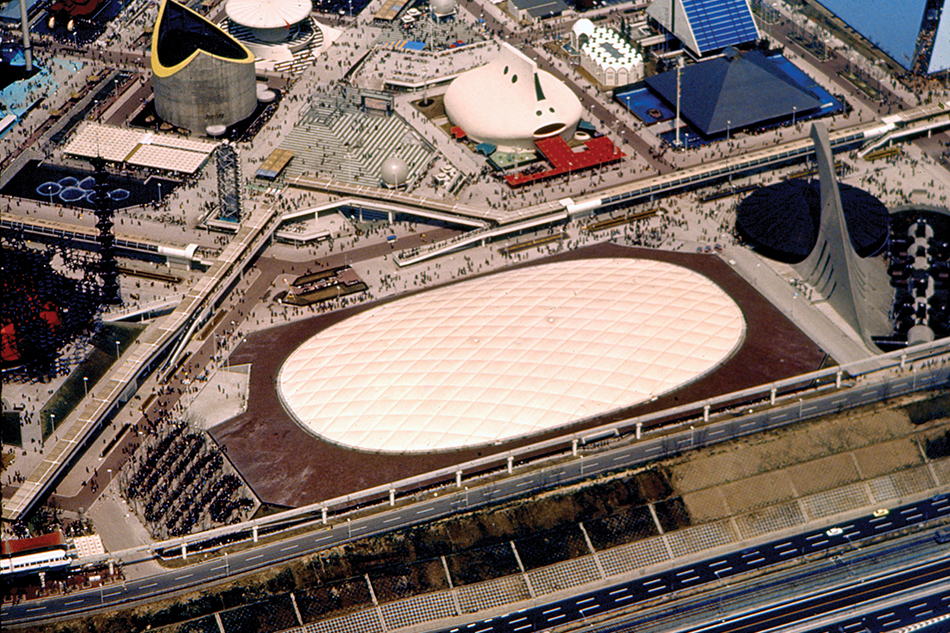

Masey later brought in the renowned Chermayeff and his Massachusetts-based design firm, Cambridge Seven Associates, to create exhibition graphics, logos and branding for “Destination Moon,” at the 1967 International and Universal Exposition in Montreal, and for an Apollo space capsule display in the U.S. pavilion at Japan’s Expo 70, in Osaka, both of which are featured at MODA. Chermayeff told Wulf that his design team had aimed to “show that America is an extraordinary place, the most creative and entrepreneurial nation on the planet.”

The MODA show’s title is somewhat tongue-in-cheek. Not all of America’s greatness was make-believe. At the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels, an exhibit designed by Leo Lionni, a children’s book illustrator, started by addressing the country’s racial ills, then ended with images of diverse children holding hands. “We were acknowledging that America isn’t perfect but that it’s still a pretty good place,” Wulf says. These cultural exhibitions, he adds, “were an idealistic form of diplomacy,” one that he feels no longer exists.

The federal government hasn’t had a cultural-diplomacy arm since 1999, when President Bill Clinton canceled the USIA’s programs and Congress ceased to pay for such exhibitions, leaving them to private funding. “It was not so much about showing Russians an Eames chair or a pair of Levis,” says Wulf, “but what these things symbolized about America. It was a demonstration of creative freedom. When there are no strictures holding you down, you can imagine worlds. And that’s what these designers did.”