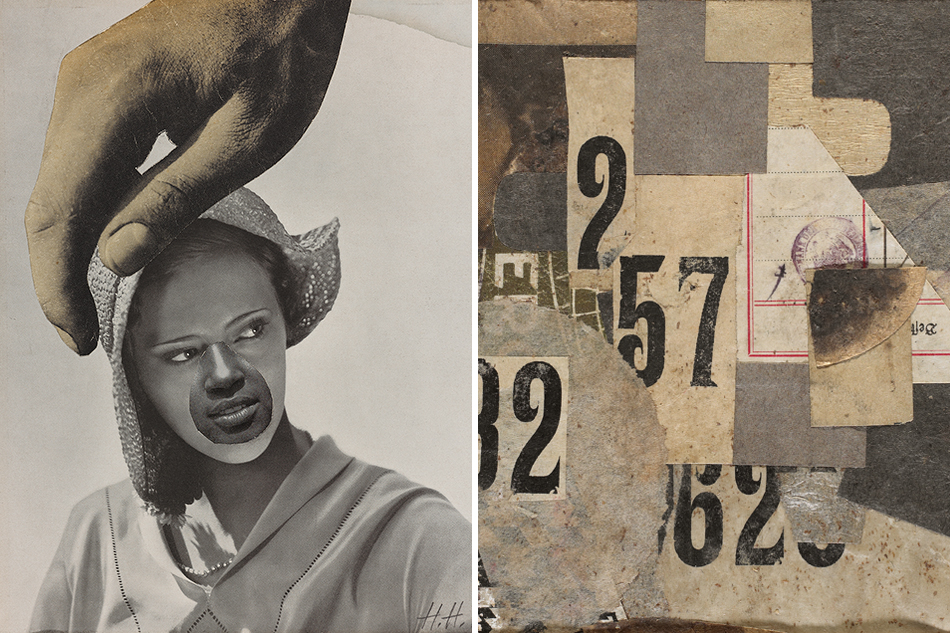

May 2, 2016“MashUp: The Birth of Modern Culture,” at the Vancouver Art Gallery through June 12, traces the roots of a contemporary artistic phenomenon back to the mid-19th and early 20th centuries, which is when Pablo Picasso began incorporating collage into such works as Nature morte, bouteille et verre, 1913, on view in the show (Artwork © Picasso Estate / SODRAC (2016) Photo by Walter Klein, Düsseldorf). Top: Barbara Kruger created the site-specific installation Untitled (SmashUp), 2016, for the show. Photo by Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery

A “mash-up,” one of those buzzwords that seems utterly of the moment, is defined in the Urban Dictionary as “a song comprised of elements of two or more pre-existing pieces of music.” And while it’s clearly relevant to the digital age — with homemade music mash-ups flooding YouTube and record producers churning out mixes by the dozen — the term, in fact, dates to the 19th century, when it was originally used to describe the mixing of two different languages.

For the epic exhibition “MashUp: The Birth of Modern Culture,” on view through June 12 at the Vancouver Art Gallery, the word has been wisely adopted to cover all the “mixing, blending and reconfiguration of existing materials (sounds, images, objects, events) to produce a new outcome,” writes VAG senior curator Bruce Grenville in the show’s dynamic catalogue. This game-changing mode of creativity has been driving avant-garde cultural production since the early 20th century, Grenville notes, but “MashUp” is the first major exhibition ever to cover the subject in such depth, or to put a name to it, for that matter.

A mind-blowing mash-up itself, the exhibition is the most ambitious the VAG has ever organized, filling all four floors of the museum’s building with nearly 400 works by more than 150 artists, designers, architects, filmmakers and musicians. Grenville co-organized the show alongside the VAG’s Daina Augaitis and Stephanie Rebick, with input from more than 25 outside curators, academics, critics and writers from around the world (including Michael Darling, of the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art; Ralph Rugoff, director of London’s Hayward Gallery; and David White, senior curator of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation). The collaborations yielded some stellar loans, which make up the majority of works in the show.

Brian Jungen’s Prototype for New Understanding #2, 1998, turns Nike Air Jordans into an evocative mask. Photo by Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery

Chronologically, the show begins in the early 1900s, with collage, montage and the readymade, but the idea of mashing up began percolating even earlier. “We thought it was wonderful that the term ‘mash-up’ actually started in the middle of the eighteen-fifties,” Grenville says, “since that coincided with what we thought would be a starting point, which is the emergence of photography and lithography and printing that produced a whole wealth of images and made it possible to imagine collage in a way that hadn’t been possible before.” The kind of mash-ups the curator and his cohort gathered together aren’t merely about collage or appropriation. Here, seemingly incongruous genres seamlessly combine: architecture meets video, design meets noise, photography meets sculpture.

This is a wildly varied group of artworks, ranging from collages by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque to “Combines” by Robert Rauschenberg, films by Jean-Luc Godard and Quentin Tarantino, music tracks by Jamaican dub innovator Lee “Scratch” Perry and audio mixmaster Danger Mouse and a text-filled architectural installation by Barbara Kruger. The thread that holds it all together, aside from the mere fact that these are all mash-ups, is technology, Grenville points out.

Advances in printing and photography in the early 20th century obviously expanded the artist’s toolbox, adding to the mix mass-produced found materials like newspapers, journals and wallpapers, which were suddenly cheap and available. As the exhibition wends its way through the 20th century and into the digital age, we see just how profound an impact technological advances have had on cutting-edge art making, decade after decade. “What we saw in the early twentieth century with printed materials happens again in the postwar period with the spread of advertising and inexpensive printing technologies, broadcast film and television,” Grenville says. “And then, in the digital age, technology just completely overwhelms everything, and nothing seems to happen without the digital on some basic level.”

One of the earlier works in the show, Picasso’s circa 1912 Guitar on a Table, might seem tame compared with some of the more contemporary works that mix sculpture, architecture, digital images, typography and any other number of media — pieces by Simon Denny or Ken Okiishi, for example. But when Picasso made it, the little snippet of prefabricated wallpaper he pasted in an otherwise black-and-white charcoal drawing must have looked as unexpected as the artist’s abstracted guitar.

The mash-up has been driving avant-garde cultural production since the early 20th century, but this is the first major exhibition ever to cover the subject in such depth, or to put a name to it.

Readymades like Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel, 1913 (6th version 1964), appear throughout the show. © Estate of Marcel Duchamp / SODRAC (2015)

The early 20th century was clearly a groundbreaking time. The mash-up mentality was in full swing by about 1920, when Kurt Schwitters began making his “Merz” constructions, composed of rubbish, and Hannah Höch was cutting up magazine pages to create her disturbing photomontages in the early 1930s. That kind of transformation of salvaged materials is something that resurfaces again and again, from Rauschenberg’s combines to Fuck the Bauhaus (2000), German artist Isa Genzken’s notorious takedown of the design movement’s purity and rationalism, constructed of plywood pillars topped with pizza boxes, construction netting, toy cars, shells, Plexiglas and other detritus cobbled together into a kind of crude cityscape.

Perhaps the strongest voice throughout the show is that of Marcel Duchamp, whose six works on view include versions of his Bicycle Wheel and Fountain (the famous urinal that he signed R.Mutt). “The bicycle wheel is this sort of readymade form that reasserts itself in all of the floors of the exhibition in different kinds of ways,” says Grenville. “This was a mode of creativity that really emerged out of a different set of rules that were defined in the early 1900s and have shifted with technology and ideology down through the century to where we are now.”

For Rauschenberg, who had his own passion for wheels, the mash-up comes in the form of the rarely exhibited Revolver II, 1967, five rotating Plexiglas discs silkscreened with images and installed in a base with an electric motor. Viewers press a button to activate the motor, which spins the discs to generate different configurations of images from the random alignment of the silkscreens. “What it does is tie together Rauschenberg’s interest in technology and collaboration” — with the viewer, here —“which was something that was of great interest to him and is often underestimated,” says Grenville. “People are just stunned at the sort of pleasure that it produces, but also that you can touch it and work it. It’s kind of hilarious because you have to press the button really hard.”

A Panel of Experts, 1982, by Jean-Michel Basquiat, combines text and drawing in acrylic and oil pastel on paper mounted on canvas. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat / SODRAC (2016), courtesy of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

In the show’s catalogue, Grenville describes a readymade as “an everyday object positioned and altered in such a way that it is impossible to use it for its original purpose.” While there are salvaged, found readymade objects transformed into original artworks throughout the show, the curators did an especially fantastic job of pointing out how the readymade opened up new doors for musicians, video artists and filmmakers on the vanguard to push their experimentation. Grenville points to the early 20th-century musician Luigi Russolo, whose sounds fill the galleries (along with those of many others). “His idea of the sounds of the city and urban life creating another kind of musical instrument radically shifts the idea of what constitutes a sound,” he says. “It’s the mashing up in a sense of both the history of music and the sounds of a city.” For Dara Birnbaum, in her landmark video Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978–79), the readymade takes the shape of television footage that she edits to create her own looping, fragmented version of TV star Lynda Carter’s metamorphosis into a superhero.

Even the fields of architecture and design have had significant mash-up moments. For his Santa Monica residence (1977–78), Frank Gehry incorporated the language of urban Los Angeles — chainlink fence, corrugated sheet metal and concrete blocks — into the design of an existing house. In another riff on the readymade, designer Tobias Wong “hacked” (as the catalogue describes it) existing design objects. His Doorstop (2003) is a block of concrete cast directly from an Alvar Aalto undulating glass Savoy vase, which was inevitably destroyed in the casting process.

Such a show would be incomplete without a good dose of Andy Warhol, who inexorably changed the course of contemporary art with his transformations into fine art of found imagery from the news, advertising, consumer culture and Hollywood. Along with prints of Marilyn and Jackie, the show features Warhol’s “Electric Chair” series, based on a 1953 newspaper photo of Sing Sing Prison, where Americans Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed for giving Russia details about the atomic bomb. The connection to Schwitters, Höch and even Picasso and Braque has never been clearer. Says Grenville: “One of the things we really loved about the show was being able to make connections.”