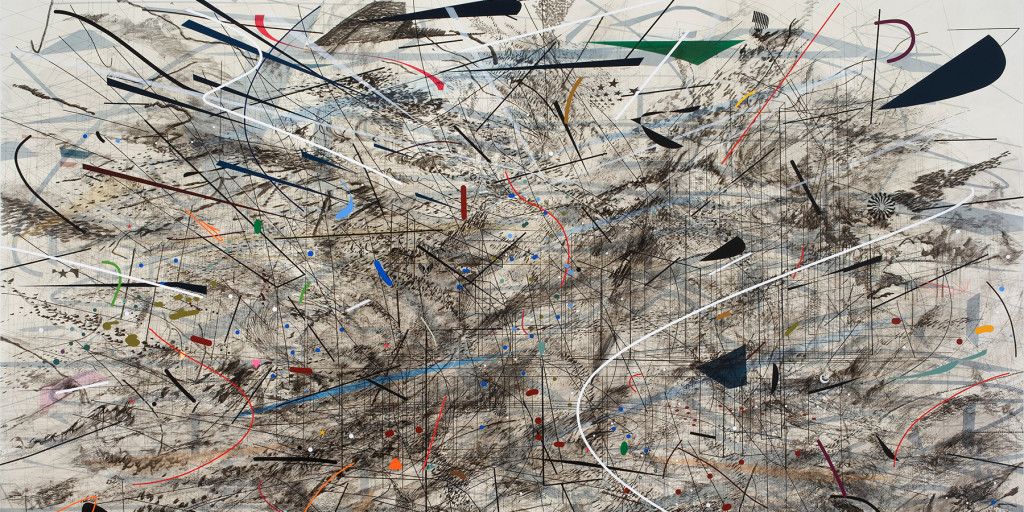

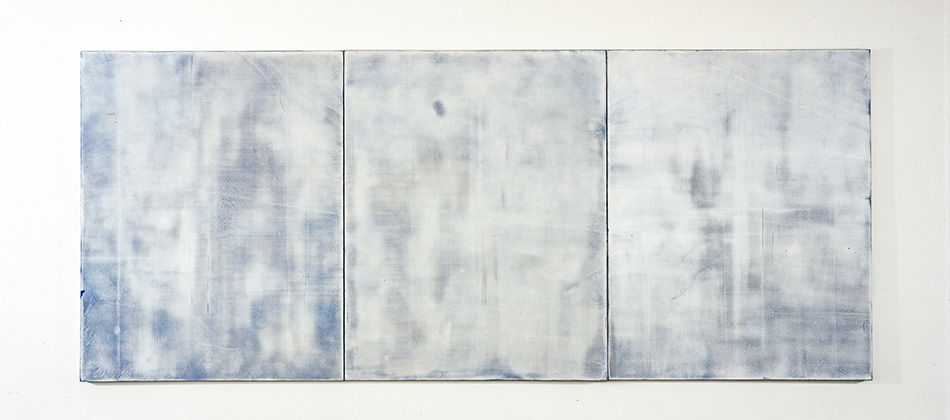

August 1, 2012Despite the current controversy engulfing Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art, Jeffrey Deitch, its director, has curated a stellar show focused on abstraction after Warhol. The exhibition features a range of works by contemporary artists, including Christopher Wool’s Untitled, 2011, seen here (courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York). Top: Black City, 2007, by Julie Mehretu (courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York).

It has been a rocky road for former New York dealer Jeffrey Deitch since his January 2010 appointment as director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Deitch’s projects have consistently come under fire as being more about hype than scholarship. Yet several of the exhibitions under his watch — such as those on street art and the work of the late actor and artist Dennis Hopper — have drawn record crowds and make a case, according to Deitch supporters, for a broader, populist outreach beyond the typically elite audiences of hoity-toity white cubes.

Though no one is willing to go on record to confirm that Deitch canned Paul Schimmel — MOCA’s beloved, intellectually rigorous chief curator since 1990 — most observers were not shocked by their recent parting of ways. After all, they are two strong, bright men with irreconcilably different (read: acrimonious) visions about the role of art in culture, the future of MOCA (and of museums generally) and, indeed, how art venues are to survive and stay relevant in these fiscally challenged and youth-driven times.

Despite critiques that he’s lightweight or celebrity-obsessed, it’s hard to deny that Deitch has enjoyed some thoughtful, handsome successes since coming to Los Angeles. Case in point: his current “The Painting Factory: Abstraction After Warhol,” which remains on view at MOCA through August 20. (Rizzoli will release an accompanying book in September.)

The very title is provocative for several reasons, not least of which is the fact that we never associate Andy Warhol with “abstract painting.” His “factory” sensibility and his carefully cultivated persona show a Warhol insouciantly dissing revered canvases made by such hard-drinking, butt-kicking, womanizing, deeply brooding macho males as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

With his tongue pressed firmly to his cheek, Warhol wanted us to think he was “a surface,” but the MOCA show reminds us that he was a richly inventive artist. His lasting legacy on abstract painting is Deitch’s main curatorial premise here. Warhol’s late-career output, which consisted of lesser known, highly experimental, oft-panned mixed-media abstract paintings — autistic on the outside, fulsome if you dig a bit deeper — have had a fertile impact on a current crop of internationally touted, newly minted art stars. These youngish artists, including Julie Mehretu, Glenn Ligon, Josh Smith and Sterling Ruby, tend to avoid the brushed mark of AbEx, know its beleaguered history inside out and, like Warhol, relish in a naughty, hybridized multimedia version of that once-sacrosanct style.

Warhol’s Rorschach, 1984, Collection of The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, © 2012 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Also like Warhol, who was able to instill (i.e. abstract) in succinct, even silly objects, very complex content — sexual identity, erotic desire, mass media, the allure of fame, the seduction of violence — these artists use diverse mechanical and natural materials (discarded paper, dust, rope, chocolate, accidentally blotted ink) to make gorgeous surfaces equally rife with ideas about race, personal history, Marxist exchange, queerness, the cosmos, decay, just to name a few.

Deitch recently spoke with Introspective about the exhibition and touched on the current brouhaha at his institution.

Could we begin with the exhibition’s title?

Titles are very important to me. They have to offer a light but accurate explanation of what you are up to, yet stay provocative, make you think. A title for a show has to say in a few words a great deal about very complicated things — a little like an artist has to convey very complex things within a rectangle.

Is the title a sort of ironic riddle, or am I reading too much into it?

You are right: It is a reference to the actual space where Warhol worked on 47th Street, to the whole idea of assistants cranking out products and to the history of elite abstract painting.

The show telescopes us between the ’60s — Warhol’s era — and the blue-chippers of 2012. How did this idea come to pass?

Look, no exhibition is a whim about art stars. It takes years and careful consideration to put on any show. This one was more than twenty years in the making.

Literally?

It started with a show I did in Japan in 1991 called “Strange Abstraction.” Even then I was trying to place abstract art in a clearer historical perspective. In long discussions with Christopher Wool back then, he mentioned he was really struck by Warhol’s abstract paintings. The paintings were very little studied, rarely talked about, dismissed — to some extent they still are — but it is work that I always had a serious conceptual interest in, ever since my friendship with Andy.

A gallery of works by Wool appear to be in direct conversation with Warhol’s Rorschach, seen above. Photo by Brian Forrest, courtesy of MOCA

And now Wool’s pretty spectacular black silkscreened gestures are in this show.

Wool is a great example of the way I approached each artist’s direct or indirect connection to Warhol. Wool is an artist who works completely alone, with his hands, no helpers, in a very traditional, quite painterly, un-Andy manner.

But his work relies on the random accidents of the screening process, the clogs and drips. Though there are no pop images and these are grand and gestural, he is using that selective smudged registration that Warhol used in everything from the Marilyns on down.

Wool, like many of the artists shown, relishes in the imprecisions that happen with, or in spite of, the precise mechanical tools artists in a media age can use. Many of the artists I selected borrow Warhol’s way of reveling in mistakes, celebrating chance — the opposite of complete control that became the basis for very severe abstraction in the 1960s.

Did these artists acknowledge ties to Warhol or was it a bit of getting the new wave of the hottest artists to fit a concept that surfaced after the fact?

It has always been very important to me that artists included in my shows really reflect the theme of the show, that there be a conceptual integrity to the project. Quite contrary to some suggestions, I am absolutely opposed to force-fitting an artist with name cachet into a show that stretches the artist’s intent ridiculously. With all these artists, the connection was clear.

So Warhol provides a stimulus. What are some of the things we see in this work that are of this moment, of 2012?

These artists are all very well-versed in every style and tradition before and since AbEx, from Expressionism to Pop to minimal art, and they use it all with smart freedom. Where traditional abstract paintings were an attempt to purify the canvas so that less and less was included, these artists use everything — conceptual art, installation, performance — and pull influences from everywhere — Warhol, Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter, and so on.

What are some specific themes or ideas that come up?

More than Warhol could have ever imagined, we live in a mediated world — our experience is made and lived through media — TV, film, digital info. These artists, such as Kerstin Brätsch, who is a founding member of DAS INSTITUT and showed at the 2011 Venice Biennale, talk pretty brilliantly about our highly mediated world.

Ghost and Stooges, 2011 (detail), by Mark Bradford. Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Brätsch shows those huge floral-like organic shapes hung on walls in a very traditional manner but then suspends gorgeously constructed transparent gels in neon colors from the ceiling mid-gallery so you’re forced to see the paintings from a variety of broken sight lines. And these colored veneers are a bodily, spatial and lyrical way to suggest that perception today is always filtered and our visual kaleidoscope is exhilarating, psychedelic and fragmenting.

Also, most all of these artists do not use a brush in a sort of deliberate dialogue with older notions about abstraction. Instead they rely on a variety of mediated — there’s that concept again — mechanical means, but they are always employing these processes directly with their hands, in very physical and intimate ways.

So the painted gesture but a step removed.

A good example is Mark Bradford. He uses neither paint nor brushes in his work, but it involves the most deliberate, tactile, exacting handwork. He is using layer upon layer of found paper and an industrial-grade sander and knife on the surfaces that he moves painstakingly by hand.

You get a beautiful feel of visual lushness, sheer beauty and gathering detritus all at the same time.

And that is the perfect description of what Los Angeles is to him: abstraction loaded with content.

Bradford is astoundingly articulate and intellectual — the opposite of how history recalls Warhol. Bradford explains that he came to his use of found paper from memories of the papers he saw his mother use as a hairdresser in the “hood.” As a gay man and a gay artist of color from the margins, this medium talks in really poignant ways about his biography and identity.

No matter how surface-oriented Warhol was — in both senses of that term — or how process-based these current works are, there’s dense content embedded in both. That was what I saw in conceiving the show.

Untitled, detail, 1987, by Rudolph Stingel. © Rudolf Stingel, courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

There’s also in much of the work on view a kind of playing with the gray area between figuration and abstraction; as a graphic artist, Warhol knew there’s always a link between an abstract shape, a mark or even lettering, and strong emotional and narrative content.

Glenn Ligon, who had a wonderful show at the Whitney last year, deals with this; he shows amorphous surfaces he builds up from actual coal dust, and in them, shadowy figures coalesce and hide again, in and out of our reading, like they are in a fog.

You include Warhol’s Rorschach and Camouflage paintings, and those do not tend to get a good critical response. Are they here to indicate a hub out of which these current spokes emanate?

Otherwise judicious L.A. critics don’t get the significance of the Rorschachs or the Oxidation paintings or their impact on painting over the last decades. The Oxidation paintings, which aren’t in the show, were made from a friend’s urine. The sumptuous colors and shapes Andy got were the product of random reactions of the acid and the surface. I cannot imagine a more clever way to challenge the “purity” and “maleness” of abstraction.

His abstract paintings are mostly seen as a late-career Warhol just trying anything, almost out of boredom. Somehow, I doubt it was that simplistic.

I had the good fortune of knowing Andy really well over many years, and we were working on a project with the Rorschachs that would have made his intentions clearer. Unfortunately, he died before we could realize the idea.

What was it?

He’d made the Rorschach blots and was very interested in the whole idea of something abstract or meaningless accruing meaning, and a different, maybe even aberrant, meaning to whomever “read” it. That is a central theme in this show. So he suggested that I walk onto the Manhattan sidewalk and show images of the paintings to passersby and have them “read” the blots. We would record responses and publish a book that had on one page the Warhol work and on the other, a running text of what people said they saw.

Kelley Walker’s Black Star Press (rotated 90 degrees), detail, 2006. © Kelley Walker. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

I have always suspected all the talk of Warhol as a mute and distant voyeur is mostly hype. As you got to know him, what did you find?

At Citibank [where Deitch created an art-advisory and art-finance division], I had to write auction reports, and he loved to come along. Eventually, I planned one of the first contemporary gallery shows in Asia and suggested Warhol make an appearance. He did, it was a great success. When you travel with someone, you really get to know them, so we became real friends. All the “I am a surface” stuff was how he packaged the product of Warhol. When one got close, that guard came down and he was a wonderful, witty conversationalist and his ideas on art were very sophisticated and risky.

As are the ideas of his artistic progeny you’ve gathered for this show. So as not to avoid the elephant in the room, do you want to comment on the current hubbub at MOCA?

Not really. Enough’s been said. I just find it interesting that in all the talk of celebrity this and celebrity that, no one has bothered until this talk to really look at and engage in a dialogue about the highly conceptual, very thoughtful shows, such as this one, that we put on all the time.