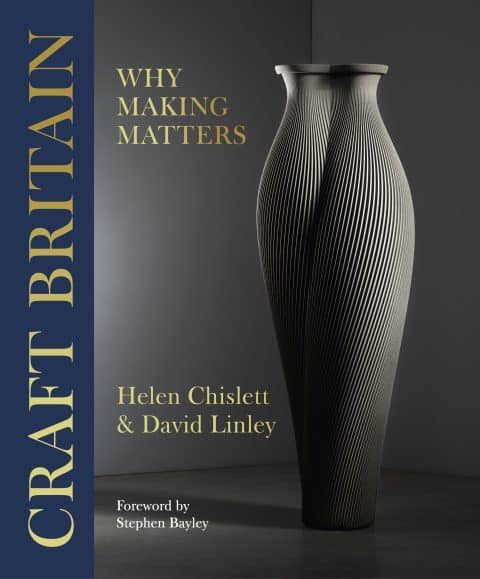

November 27, 2022Lord Snowdon, better known by the name of David Linley, and I are pleased and excited that our book, Craft Britain: Why Making Matters, has transformed from a conversation we started in 2019 into something we can physically hold in our hands. We began talking about this idea pre-pandemic, determined to bang the drum for crafts and craftsmanship across Britain.

David and I met in 1997 at a workshop in Whitby, North Yorkshire, one of many where Linley, the company that David founded in 1985, had its extraordinarily fine furniture made. We ate fish and chips out of newspaper, the air thick with sawdust, raising our voices to be heard above the din of saws and sanding machines. I was interviewing him for a Sunday newspaper, and once I had filed the copy, our paths might never have crossed again. Yet we discovered an affinity that day for all things craft that has come to fruition in the pages of our book.

Back in the late 1990s, craft was far from popular — considered unfashionable, uncool and largely irrelevant. Since then, it has exploded into the contemporary consciousness, enjoying a renaissance and an influence well beyond the world of design. We are now awash in artisan coffee, craft beer, handmade soap and so forth. This is very encouraging for the future of craft and craftsmanship, but we can’t let them slide into nostalgic whimsy. They have to stay relevant to really thrive. As David is keen to emphasize, “The postwar industrialized world may have driven a wedge between us and the natural human process of making, but we can learn from the past, recognizing that skills that harness the mind, imagination, hand and eye are as relevant and important to our future as ever before.”

One thing we were determined to do within this book was embrace all aspects of craft and craftsmanship, from heritage to contemporary. Craft is not as easy to pin down as people may think. It forms a triumvirate with art and design, often blurring the boundaries and challenging preconceptions — just think of Grayson Perry’s pots, Tracey Emin’s appliqué textiles and Gavin Turk’s needlework.

“Craft is often defined as the skill of making something by hand, but if the resulting object is a dry-stone wall on a Derbyshire dale, it is perceived as something quite different from a hand-blown-glass vessel in an international art fair,” we note in our introduction. “Both are craft, but one is seen as purely functional, whereas the other is seen as akin to fine art. If a table is made by a local carpenter, it is craft. If it is made in a workshop headed up by a designer-maker (who may or may not be personally involved with its making), it is perceived as a piece of custom design. The fact is that — like art — craft is a word that people use in different contexts to mean different things to different people. Our own view is that it is all valid and valuable, that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.”

Chislett, left, met Linley (who is the nephew of Queen Elizabeth II and first cousin of King Charles III) in 1997, when she interviewed him at a workshop that was producing his company’s designs. Photos, from left, by Alun Callender and courtesy of David Linley

To this end, we organized our book around 12 themes, which include “Heritage & History,” “Rare & Endangered,” “Kind & Sustainable,” “Health & Wellbeing,” “Masterful & Magical” and “Collected & Curated.” Within these, we have spotlighted the work of a few individual makers to highlight the wider issues we are raising.

Of course, Britain’s rich culture and history define it as a nation. Membership in the National Trust, an organization founded in 1895 to help preserve Britain’s many important historic buildings, is currently heading toward the six million mark — bigger than the entire population of such countries as Costa Rica, New Zealand and Norway.

In “History & Heritage” we explore this legacy. “Our cities, towns and villages are crammed with portals to the past in the shape of cathedrals, castles, palaces and monuments,” we observe. “We are blessed to live in a place where we are never more than a few miles from a piece of our human history, from the stateliest of country houses to the humblest of country churches. We have around twenty thousand scheduled monuments, upwards of sixteen hundred registered parks and gardens, over thirty World Heritage sites and almost half a million listed buildings. These add up to a built heritage of cultural, religious, archaeological and industrial significance, dating from circa 4000 BCE to the twentieth century.”

This wealth of history relies on those with hand skills to preserve and protect it. HM King Charles III recognized this need many years ago, and his personal charity, the Prince’s Foundation, does extraordinary work in encouraging new generations of makers into the heritage sector through initiatives such as the Building Craft Programme. This gives those from building trades the opportunity to elevate their skills to the level required within the heritage sector, with many finding new roles in the maintenance of castles, cathedrals and grand country estates. (The exhibition “Bespoke for a Book,” on view at the organization’s Garrison Chapel space December 6 through 16, will display bespoke boxes and bags created and generously donated by 32 makers highlighted in Craft Britain, each containing a signed copy of the book. All proceeds from sales of the one-off works will benefit the foundation.)

However, we were also determined to highlight the work of the many contemporary makers working in Britain (not necessarily born in the country) whose creations are often to be found at international art fairs and on sites like 1stDibs. We talked to leading London gallerists in the decorative-arts sphere, such as Angel Monzon, of Vessel Gallery. Monzon introduced us to makers like Samantha Donaldson, who exploits hot blown glass to create brilliant layers of color, and Nina Casson McGarva, who transforms it into highly complex structures inspired by details within nature.

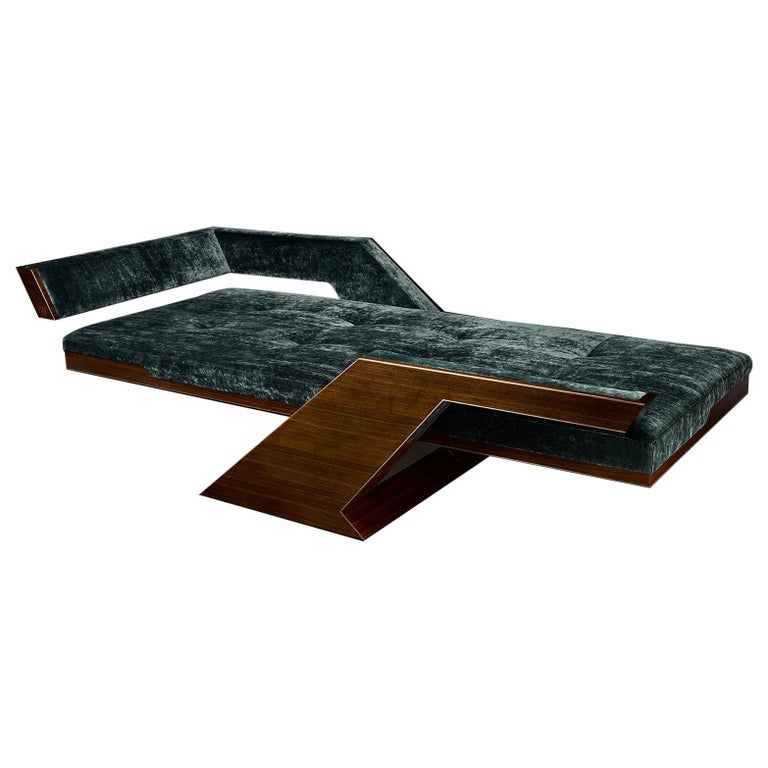

It was also important to us that we cite those whose work includes craft practices but sits within the overlapping spheres of fine art and collectible design — artists such as Laura Ellen Bacon, who uses materials like woven willow and stone to create forms that are both intimate and muscular; Danny Lane, who is internationally renowned for his glass and steel structures; and Tom Vaughan, who is best known for the way he manipulates timber and metal into pieces of functional sculpture.

In addition, we have looked at how artists collaborate with craft ateliers. One example is the incredible tapestries produced by Dovecot Studios in collaboration with leading contemporary artists like Garry Fabian Miller and Chris Ofili.

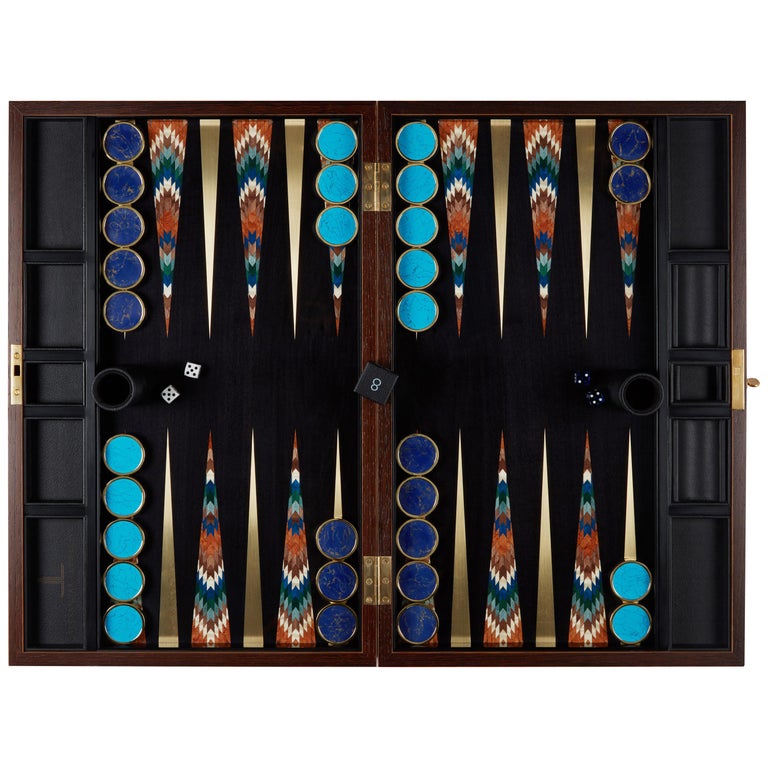

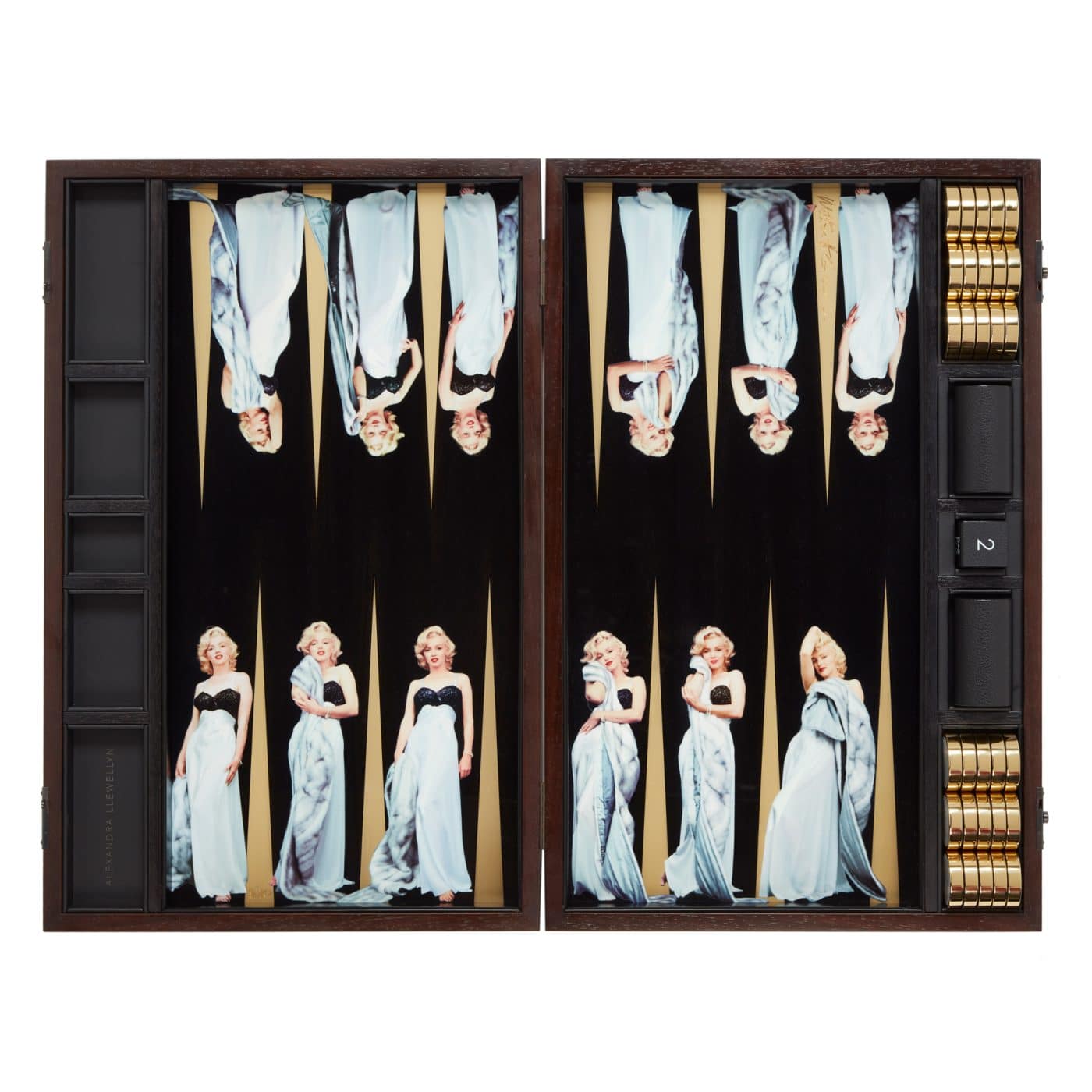

In our chapters “Unique & Personal” and “Inspirational & Aspirational,” we explore the fully bespoke possibilities of commissions by such talents as games maker extraordinaire Alexandra Llewellyn, whose backgammon boards are as apt to be inspired by an icon like Marilyn Monroe as by the flora and fauna of a tropical island; and Bill Amberg, whose atelier reinterprets traditional leather for contemporary residences around the world. And, of course, we look at the work of Linley, the cabinetmaker that David founded 30 years ago.

One important point — our book is not a directory, and we have been anxious not to imply that it is in any sense definitive. As we say in our acknowledgements, “We would like to thank the many craftspeople who have helped us put together the content of this book. We would also like to acknowledge those who may have been disappointed not to be included. We hope by raising the subject of craft so widely, everyone involved will ultimately benefit.”

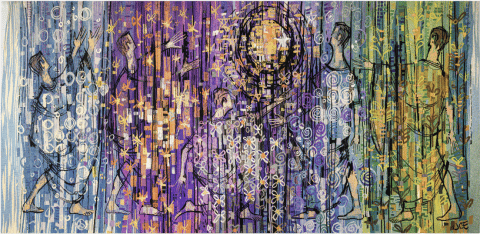

Dovecot Studios collaborates with artists to make often elaborate tapestries. The Elements, 1965, was designed by Joyce Conwy Evans.

In all, we have included the work of more than 130 makers across a breadth of disciplines. One thing that struck us through the many conversations we have had with them is that they seem to be the people who have achieved the greatest work-life balance — serene, content, enjoying each day and endlessly curious to explore and refine their exceptional skills. They are also in harmony with the landscapes around them, which, in turn, often provide the material with which they work. As oak swill basket maker Owen Jones says of the Cumbrian woods where he lives and pursues his now endangered craft, “Time has a different dimension when you are surrounded by nature. It is always an uplifting experience. Every tree is different, and each swill leaves me to go on its own journey.”

It is with the same sense of optimism that we send Craft Britain out into the world, and we hope it inspires those who read it to support crafts and craftspeople wherever possible. Who knows? It might even inspire you to take up a craft of your very own.