April 20, 2015“When I am dead and gone, people will know the 21st century was started by me.”

No one with even a scintilla of interest in fashion would argue with this statement once uttered by ALEXANDER MCQUEEN and now written on a gallery wall at the VICTORIA & ALBERT MUSEUM, in London, where the recently opened exhibition “Savage Beauty” showcases the design deity’s inimitable creations. (The show runs through August 2.)

Introspective COVERED THE ORIGINAL “SAVAGE BEAUTY” in New York, at the METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART‘s COSTUME INSTITUTE, when it debuted there in 2011. Curator Andrew Bolton’s visceral journey through the imaginative body of work McQueen produced during his brief career — he committed suicide in 2010 AT THE AGE OF 40 — was brilliant. Visitors thought so too: More than 660,000 people attended the show, making it the Met’s eighth most popular exhibition ever.

It is not surprising, then, that upon hearing about the V&A’s plans to re-stage “Savage Beauty,” many fashion insiders found it hard to imagine how a second outing — or the enthusiasm greeting it — could match what the Met achieved. But, as it turns out, Claire Wilcox, the London museum’s senior curator of fashion, has showcased McQueen’s prodigious talent in such a dramatic manner that even second-time viewers will be awed and moved. Without a doubt, “Savage Beauty” is the best fashion exhibition the V&A has put on in recent memory.

“When I am dead and gone,” McQueen once said, “people will know the 21st century was started by me.”

Wilcox has put more focus on McQueen’s London roots. Most of his degree show from Central Saint Martins is displayed along with original runway samples. (Missing in New York, many of these outfits were purchased by Isabella Blow, the fashion editor and McQueen mentor/muse who also committed suicide, in 2007.) Overall, this show displays many more designs than were seen at the Met, which is surprising since the U.K. usually proclaims small is beautiful and the U.S. big is best. The section labeled “Cabinet of Curiosities” is now twice as large, a vast black cavern where flickering videos of runway shows are interspersed with fantastical accessories against an auditory backdrop of hallucinatory music. One could spend hours in this room alone — especially if under the influence of a hallucinatory substance. (Looking around the space at my fellow show-goers, I had to wonder.)

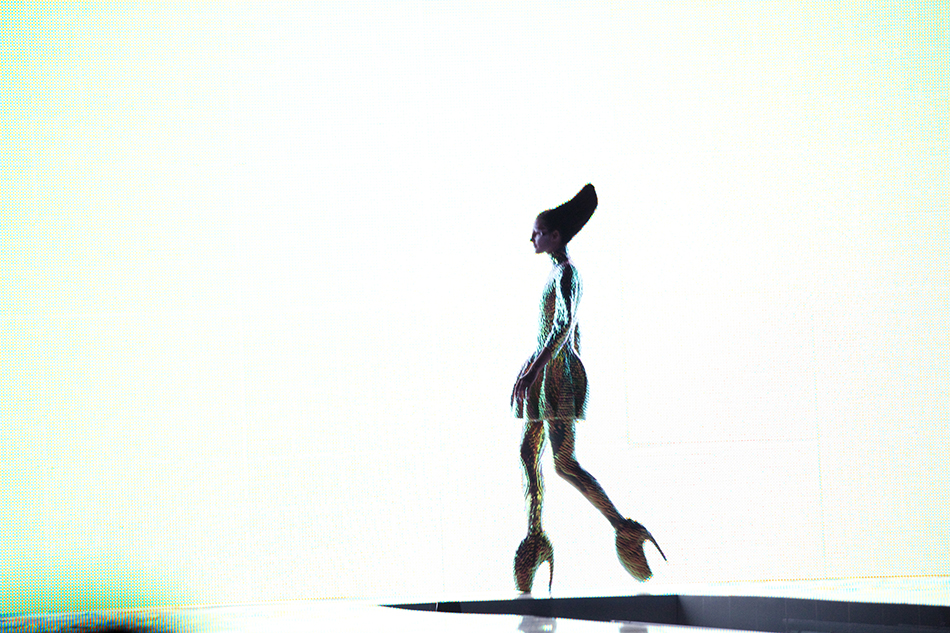

Some of the exceptional team from New York also worked on this exhibit (Bolton was consultant curator), so there is some continuity — including the much-discussed Kate Moss hologram — as well as mise-en-scène tableau and site-specific media that contextualize McQueen’s inspiration. Dresses from his final runway show, “Plato’s Atlantis,” are displayed in front of a kaleidoscopic floor to ceiling video.

Having departed from the Met’s “Savage Beauty” emotionally wrung-out, I staggered out of this version completely overwhelmed — how much brilliance can a person take? Which begs the question: How much more agonized brilliance could McQueen have lived with? Five years after his death, there is enough distance to acknowledge that, just as he said, he indeed made an indelible artistic mark that we can now see, more clearly than ever, marked the start of the 21st century.