July 20, 2015John Singer Sargent, depicted as round, ruddy-faced and wielding a delicately poised paintbrush in this caricature by Henry Tonks — who, like him, was designated an official war artist in 1918 — is the subject of two East Coast summer exhibitions (image © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Top: Group with Parasols (Siesta), 1904, included in the Met’s stunning presentation of casual portraits, demonstrates Sargent’s easy command of composition and gesture (image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), born to sophisticated American parents in Italy and raised among the fineries of upper-crust European life, is celebrated as the leading portrait painter of his generation’s transatlantic jet set — the preeminent documentarian of Edwardian-era luxe, calme et volupté. The rich, saturated surfaces of his canvases offer glimpses into the luxuries of the late-19th and early-20th century’s cultural stars, from Henry James to Auguste Rodin and Gabriel Fauré, all of whom were Sargent’s friends. Perhaps lesser known to the majority of his public, however, is that the man behind the languid scenes of privileged leisure was in fact as ironic in sensibility as he was steely in matters of commerce, a disciplined driver of his own career and a wry satirist.

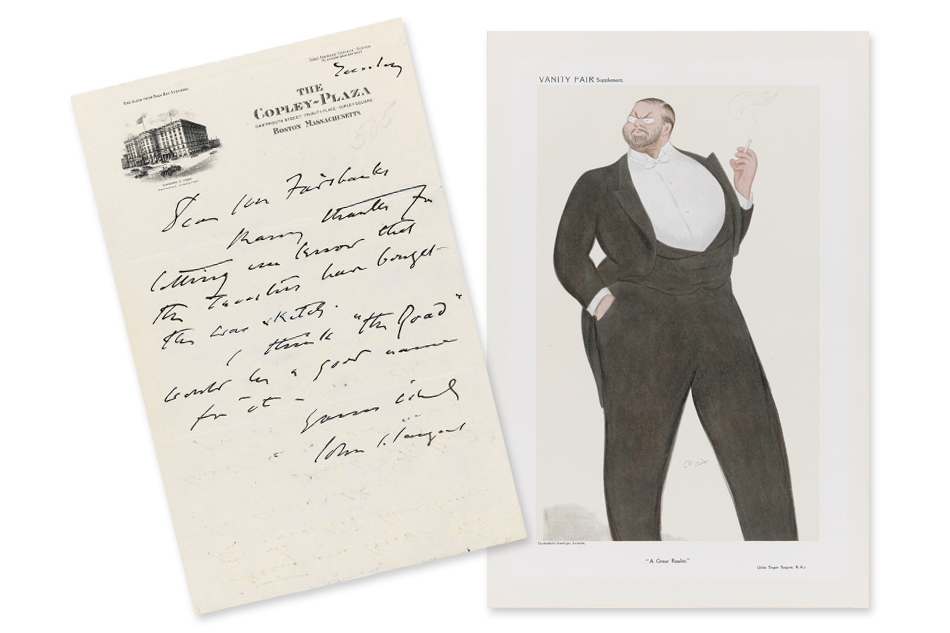

Now, an enlightening assortment of paintings and archival materials presented in a pair of East Coast exhibitions — one at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from July 25 through November 15; the other at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, through October 4 — bring the artist to life. The MFA’s “Yours Sincerely, John S. Sargent” inaugurates the newly established John Singer Sargent Archive of letters, photographs and sketches, bequeathed to the museum by the artist’s grand-nephew Richard Ormond and his wife, Leonée, together with New York art dealers Warren and Jan Adelson, of Adelson Galleries. These recent acquisitions take their place among the museum’s renowned holdings of Sargent’s paintings, sculptures, watercolors, drawings and murals, framing him as a competent businessman and a mordant critic — of his own work, as well as the work of others — and officially establishing the institution as the country’s leading center for Sargent scholarship.

“I’ve had an ongoing love affair with Sargent since my days as an art history student at Boston University,” says Warren Adelson, noting that the expatriate artist, who considered Boston his American home, has a substantial presence throughout the city’s numerous cultural spaces. “So when we wanted to find a home for this rather exceptional archive, the MFA was an obvious choice. We’ve worked out an interesting arrangement with the museum to keep the material alive going forward.”

“Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends,” at the Met through October 4, features daringly intimate images that document Sargent’s relationships with creative types of every caste, including aesthete Dr. Samuel-Jean Pozzi, whom he painted in a brazen palette of flaming reds. Image courtesy of the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

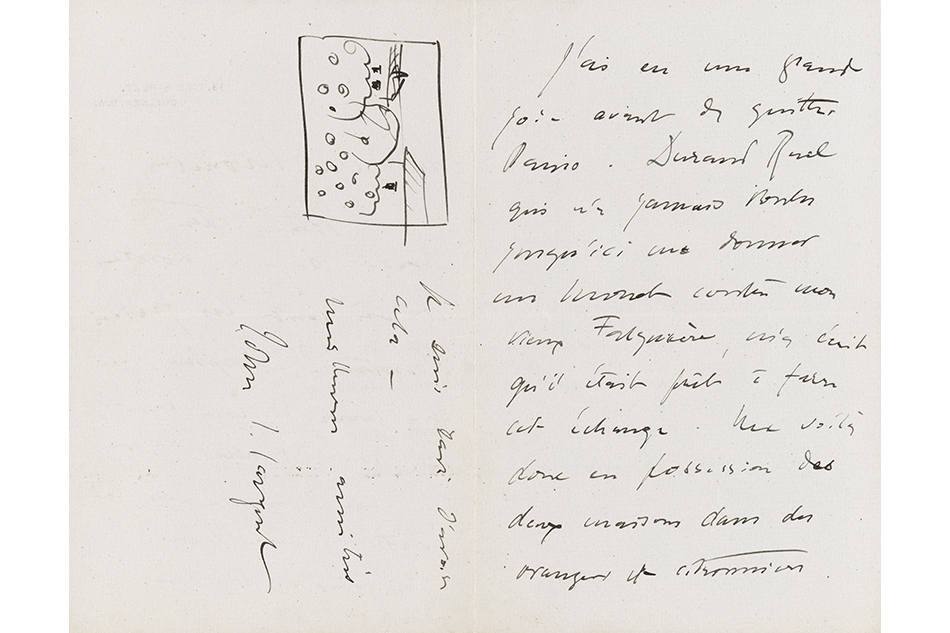

The culmination of a 35-year collecting project shared by the Adelsons and Ormond, who decided in 1980 to produce the artist’s catalogue raisonnée — the last volume will be released by Yale University Press next year — the archive includes many inherited works as well as materials and ephemera purchased over the years. “Having these objects helps us put things together in a different way and learn more about the works in our collection and about Sargent as an individual,” says MFA senior curator Erica Hirschler, who organized the show. “The letters are illuminating in many ways, giving us insight into what Sargent thought about his work — and he certainly knew that some of his paintings were better than others.”

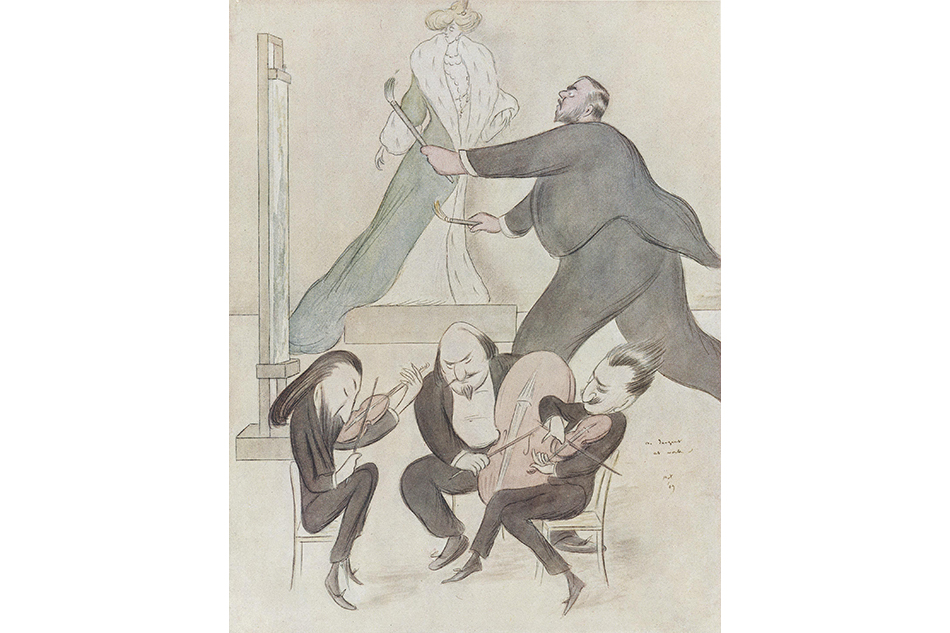

Beyond a handful of playful caricatures depicting the artist as a bloated task-master with an eternally furrowed brow, a suite of letters he sent to Walter Leighton Clark — who was organizing a retrospective of his work in New York’s Grand Central Art Gallery, which they co-founded, in 1924 — are particularly illuminating. “Sargent wrote to him every day, sometimes twice a day, about what should be in the show and where to find it, really acting as co-curator,” Hirschler adds. “It’s interesting to see an artist do all of that himself, since at that point he was very successful and must have had a complete staff — yet he’s the one writing the letters.”

Despite the vigilance he exerted over his professional life, Sargent was above all a social creature, and a comrade to many. In something of a perfect counterpoint to the MFA presentation, the Met exhibition — which is accompanied by a Rizzoli-produced catalogue — offers a taste of the vibrant, expressive portraits he painted when he was effectively “off-duty:” a series of jewel-toned vignettes that show him at his best. Here, Sargent eschews conventions of composition or form, choosing instead to portray his subjects in dynamic, candid moments. He paints Monet mid-stroke, at work plein-air in a grove of trees, and Robert Louis Stevenson mid-stride, stalking on gangly legs through a ruby-hued salon. His friends slouch in armchairs, flop and sag against each other for an alfresco nap or leer as they watch ladies paint; lips curling under tousled mustaches, chins raised easily in the painter’s direction, hands busy, they are occasionally caught at surprising angles, like fish out of water. Sargent’s friends are frozen in his frames — but they seem to bridge the decades and to enter our living, breathing world.