June 13, 2021The Brooklyn Museum’s decorative arts galleries were a comfortably familiar feature of the institution’s fourth floor for decades. Beginning in 2018, they underwent a major renovation and reinstallation — amazingly, the first overhaul since 1971— and the result is far more than a facelift. The new installation, “Design: 1880 to Now,” represents a veritable rebirth for the 3,000-square-foot-space. Previously a bit old-fashioned, the galleries today offer a fresh perspective on design, using the nearly 100 objects on display to tell the history of the decorative arts.

Curators plucked these pieces from the museum’s huge collection of more than 30,000 decorative objects, which hail from the 18th century to the present and from points around the globe. The galleries’ organizers arranged the selected items into 16 sections, including “The Aesthetic Movement and Cultural Appropriation” and “The Machine Age.”

An Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann corner cabinet on display, featuring kingwood veneer on mahogany and intricate ivory inlay, dates to 1927.

The current installation offers a less Eurocentric view of design than the former one, while still mixing in familiar pieces from the West. There are items by celebrated designers from France (Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann), Italy (Ettore Sottsass) and the United States (Norman Bel Geddes), as well as Japan (Masanori Umeda). More than half the pieces were in the galleries’ prior incarnation, but you’ll see them anew in this reimagined context.

“We wanted to rejigger them a bit,” says Aric Chen, the Shanghai-based independent curator who masterminded the new installation. “We came up with a plan to refresh the galleries and bring in new perspectives.”

Chen got to know the collection in 2017, when he completed a residency at the museum working with Barry R. Harwood, the institution’s longtime decorative arts curator, to whom the new galleries are dedicated. Harwood, who died in 2018, put a distinctive stamp on the program in his 30-year tenure, but it was time for a change.

Brooklyn Museum director Anne Pasternak says the installation “reframes” the history of design and “sparks new conversations around classic motifs.”

The most explicit and telling contrast with the old installation comes with its very first pairing of two objects: Sitting next to each other in a vitrine are Karl L.H. Mueller’s Century vase from 1876 and the Brooklyn Century vase, commissioned by the museum in 2019 from Philadelphia-based ceramist Roberto Lugo.

The latter is a direct riff on the older piece. Where Mueller’s vase celebrates the U.S. Centennial with august, gilt-edged porcelain and scenes of can-do commerce and industry, Lugo’s incorporates imagery referring to highlights of Black culture — pioneering baseball player Jackie Robinson and the rappers Jay-Z and the Notorious B.I.G. — while still finding room for elaborately rendered roses.

“The older piece is more about technological innovation,” says Catherine Futter, the senior curator of decorative arts, who started at the museum a year ago, after the reinstallation plan was already set. “Roberto’s is about social and cultural history.

“I love these vases together,” she adds. “It’s such a powerful way to start the show.”

The Brooklyn Museum has been in the vanguard of institutions radically rethinking their presentations through the lens of people of color. The two vases are “a microcosm of the changes museums are undergoing, and must undergo,” says Chen. “Roberto takes a stab at rewriting history.”

Lugo’s deft artistry also shines an illuminating light backward on Mueller’s intricate design: Despite the Victorian era’s reputation for stuffiness, its ornate visual culture is essentially bling-y. “Bling is both timeless and universal,” Chen says. “Some things never change.”

Although works by women are in the minority in the installation, there has been a meaningful attempt to incorporate female designers — a five-fold increase from the previous iteration — and many are not household names.

The section on the Machine Age displays a striking, streamlined sugar bowl and creamer in nickel silver by the Hungarian-American designer Ilonka Karasz, from 1928, as well as a five-piece glassware set by the German-American maker Elsa Tennhardt, from the same year. Karasz and Tennhardt are designers you may seek out after seeing these pieces, given their intricacy and ingenuity.

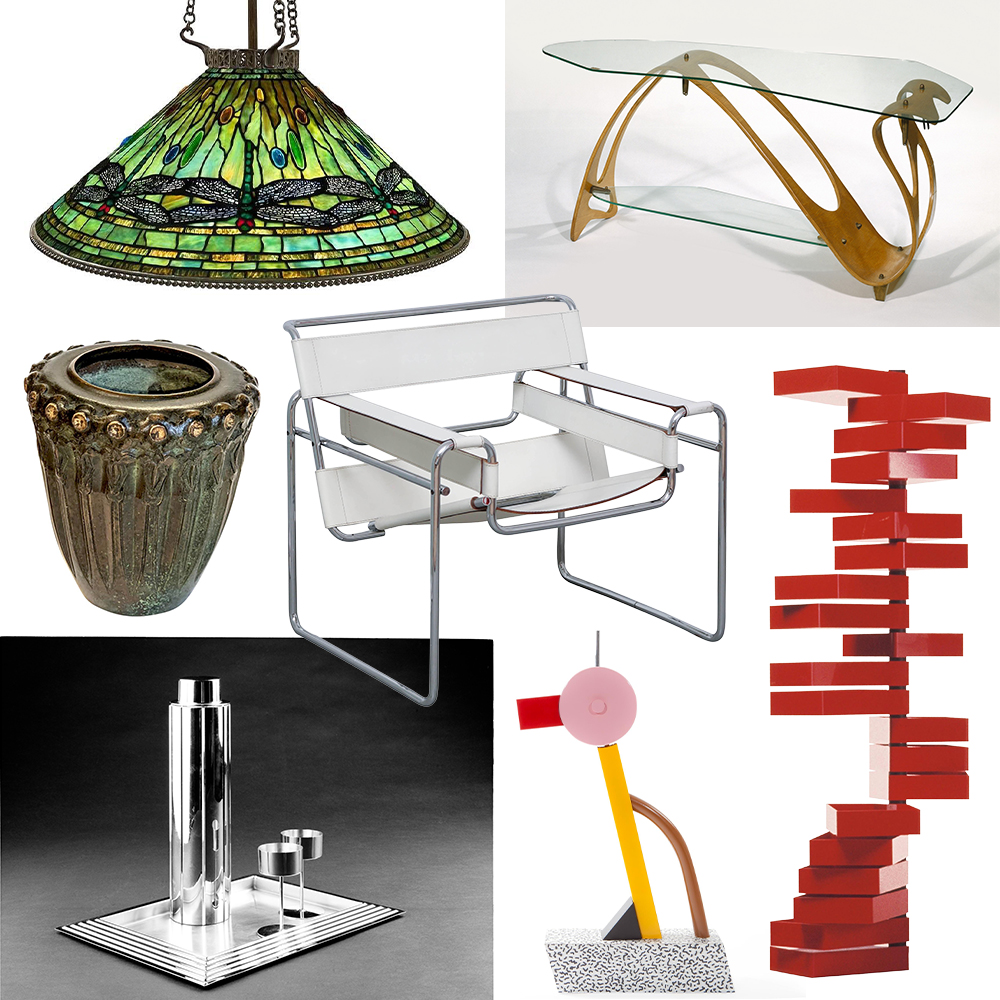

Even as the new installation showcases an array of diverse makers who’ve historically gotten less attention, it doesn’t skimp on the familiar, iconic highlights of the past century.

Three late-1920s tubular-steel pieces by Marcel Breuer are stacked against a green background. Together, his Standard-Mobel side chair model B5, Standard-Mobel armchair model B3 and Standard-Mobel table model B19 exemplify the spare, powerful achievements of the Bauhaus.

Tejo Remy, of the Dutch collective Droog Design, is represented by his now-familiar 1991 Chest of Drawers, You Can’t Lay Down Your Memories. Its series of discombobulated wooden drawers, bound together by a jute strap, demonstrates the force of a postmodern take on furniture that edges over into fine art.

But Chen’s installation also has a way of making the familiar new — he has even dusted off and put back on view some of the museum’s excellent glass pieces by Louis Comfort Tiffany, as well as ones made subsequently by Tiffany Studios and perhaps considered old-fashioned by some. “There’s value in showing something that hasn’t been seen in a while,” says Chen.

A colorful Tiffany Studios Dragonfly lamp from the first years of the 20th century was designed by Clara Wolcott Driscoll, another woman maker to note. A favrile vase by the master himself, made ca. 1900 and featuring curving leaves, shows how Tiffany drew enormous inspiration from organic forms throughout his career.

In its beauty and fragility, Chen says, “it gives us a new outlook on nature” at a time when ecological concerns fuel much of contemporary art.

The museum’s famed period rooms, located on the same floor, are mostly off view at present, except for one: The luxurious Art Deco–style Weil-Worgelt Study. A symphony of browns and tans created by the Parisian firm Alavoine in the late 1920s, the space features a large panel designed by Henri Redard and executed by Jean Dunand.

Japanese modern and contemporary design were two areas Chen wanted to beef up. The sinuous curves of a 1937 bent-plywood armchair by the designer Ubunji Kidokoro seem to anticipate much of what’s to come in later decades. Shiro Kuramata’s 1990 Feather stool — a clear acrylic block with duck feathers appearing to float inside — is a new addition to the museum.

“I was so happy, because he’s never been in the collection before,” Chen says of the piece, a gift from the contemporary-design dealer behind Chelsea’s Friedman Benda gallery, which represents the Kuramata estate.

The exhibition reaches many corners of the world, but it also looks for treasures closer to home: One wall is covered with Brooklyn Toile, from the borough’s own Flavor Paper, the cheeky firm that has helped revitalize the medium of wallpaper. The scenes depicted include the Brooklyn Bridge, a hipster on a bike, Hasidic Jews and, for the second time in this presentation, the Notorious B.I.G. (perhaps setting a new standard for appearances by rappers in a design show).

Pasternak says she relishes the Kings County references, which echo Lugo’s work from the start of the show: “The vases and the wallpaper bookend the installation, firmly grounding the collection and the installation in Brooklyn.”

Could anything be more appropriate? Fuhgeddaboutit.