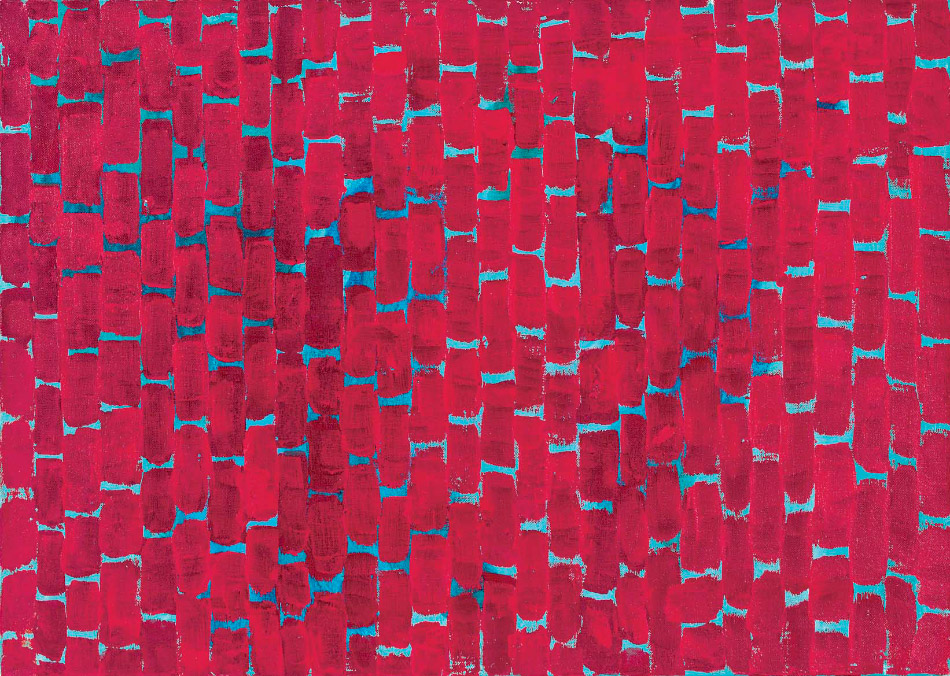

April 27, 2015The work of abstract painter Alma Thomas, seen here in 1976 at age 84, two years before her death, is currently on display at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, in New York (photo by Michael Fischer, courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum). Top: A detail of Untitled, ca. 1960 (all artwork images courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery)

In February, First Lady Michelle Obama made news when she unveiled the redecoration of the Old Family Dining Room and opened it to the public. Transformed from an American Federalist shrine into “a showcase of modern art and design,” as the White House blog puts it, the room now features four abstract artworks, all donated to the permanent White House collection for display in the room. There are two Homage to the Square compositions by Josef Albers; a 1998 digital print by Robert Rauschenberg from his Anagram (A Pun) series; and Resurrection, a luminous 1966 target painting by Alma Thomas, a little-known member of the Washington Color School group, whose members also included Morris Louis and Gene Davis.

While talking about the room on NBC’s Today show, Mrs. Obama referred to Thomas as “the first African-American female artist to be shown here at the White House.” As the First Lady spoke, Thomas’s canvas fairly glowed behind her: A joyous eruption of color in the shape of a bull’s-eye or a sunburst, its prismatic coloration, set like mosaic tiles against a white background, starts with blue at the center and radiates out to yellow in rhythmic, thumb-shaped marks.

Thomas’s installation at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue is but one in a growing number of achievements for the artist, an intriguing figure whose painting career didn’t take off until she was in her 70s, after her 1960 retirement from teaching art in a Washington, D. C., public school. Thomas then enjoyed a stunning rise to fame, which brought her shows at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and Washington’s Corcoran Museum of Art in 1972, and a posthumous retrospective at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, then the National Museum of American Art, in 1981. (She’d died three years previously.) After that, her work gradually faded from view.

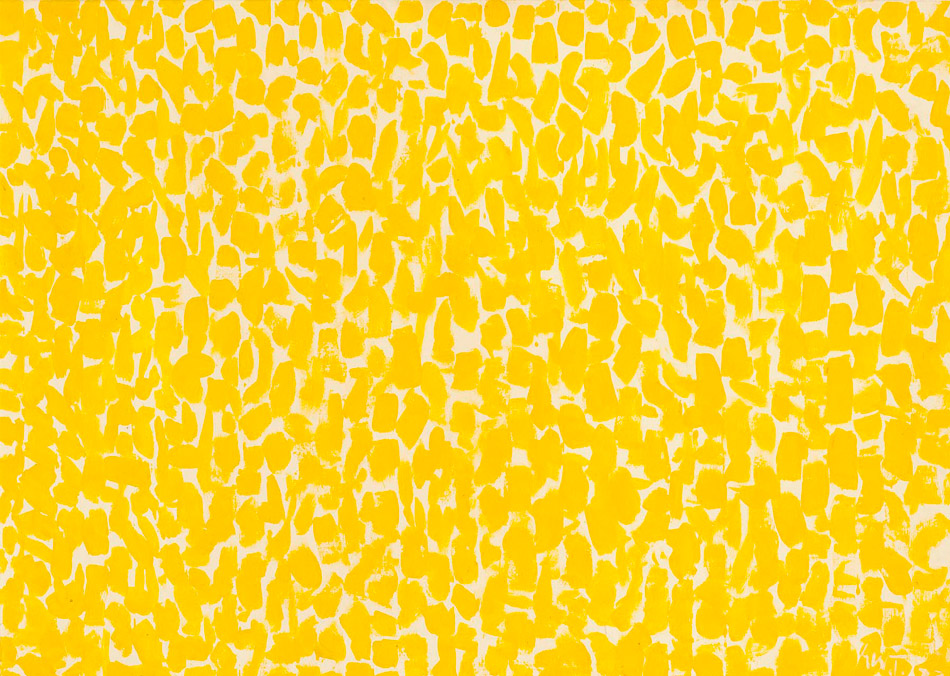

End of Autumn, 1968

Today, however, interest in her oeuvre has been renewed. In March, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, announced its acquisition of a target painting, Lunar Rendezvous — Circle of Flowers, 1969, together with work by Helen Frankenthaler and Rauschenberg. The Whitney Museum of American Art, which reopens this week in a new downtown location, has included a loosely-gridded Thomas abstraction (next to a Cy Twombly) in its first permanent collection installation. And the Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore College and the Studio Museum in Harlem are planning a full-scale Thomas retrospective, which will open at the Tang in early 2016 and travel to Harlem that summer. “The show fits perfectly with our mission of focusing on under-recognized artists and trying to make a difference in art history,” says Ian Berry, the Tang’s director. “Thomas is an artist whose work is beloved as soon as you get to see it. She makes work that transcends time.”

Thomas’s resurrection is largely due to the efforts of New York’s Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, which has championed her work since the mid-1990s, along with that of such other under-known African-American artists as Bob Thompson and Benny Andrews. Today, says Halley K. Harrisburg, the gallery’s director and co-owner, “the interest and demand for Thomas’s work is extraordinary, and international.” In fact, Thomas and the renowned Abstract Expressionist Norman Lewis, she adds, have transcended the African-American category and “are really seen as major contributors to American abstraction and calligraphic mark-making.”

The current show at Michael Rosenfeld, in New York’s Chelsea, includes 45 artworks in total, spanning the artist’s career. Photo by Matthew Newton

The gallery initially showed Thomas’s work in 1994, in the first of 10 annual “African American Art: 20th Century Masterworks” group exhibitions. In 1998, the Fort Wayne Museum of Art gave Thomas a retrospective, and the gallery has built her career slowly but steadily since then, with numerous group shows and a well-received solo exhibition, “Phantasmagoria,” in 2001, which traveled to the Women’s Museum in Dallas later that year.

“The interest and demand for Thomas’s work is extraordinary, and international.”

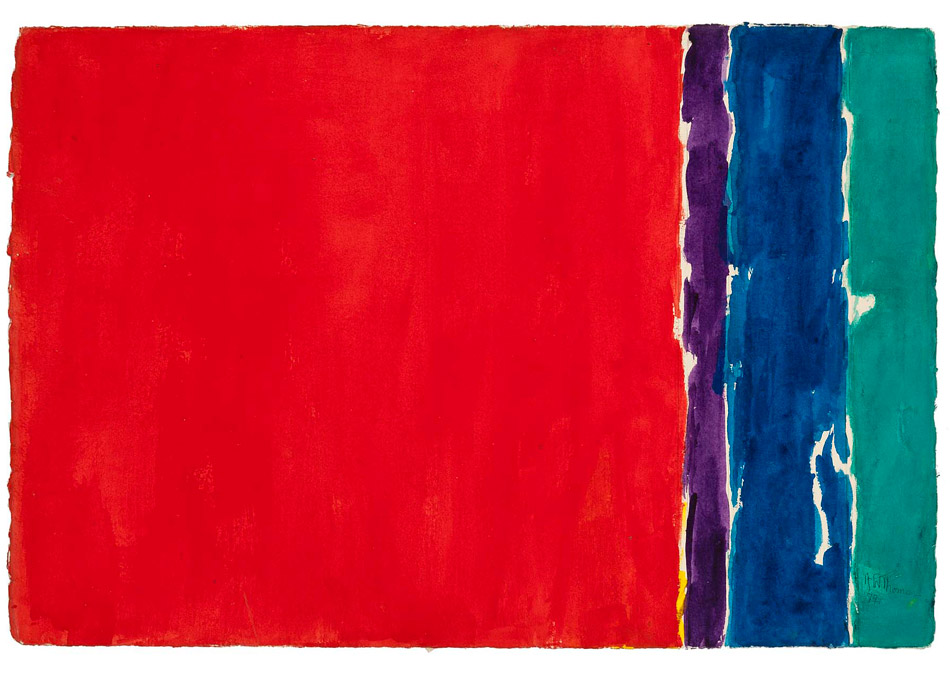

The gallery has now mounted its second solo show of the artist’s work, “Alma Thomas: Moving Heaven and Earth, Paintings and Works on Paper, 1958-1978,” on view through May 16. It includes 45 artworks in total, all acquired by the gallery over the last 15 years. (There is no estate.) The arrangement is roughly chronological, starting with Thomas’s earliest abstractions — somber, expressionistic oils made soon after she’d studied with Jacob Kainen, a painter, WPA printmaker and Smithsonian curator who helped shape the postwar Washington art scene. It concludes with the sparer, jewel-toned watercolors and acrylic-on-canvas works for which she became known.

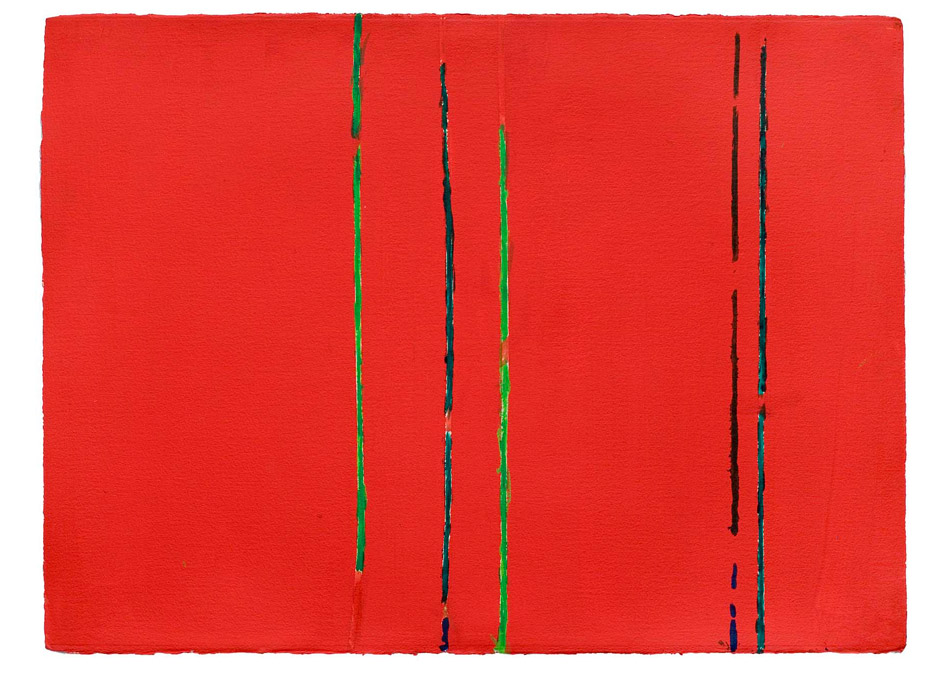

Many of the paintings suggest Thomas’s love of nature, like Deep Red Roses Chant, 1972, a field of rhythmic vermillion stripes (she called them “Alma stripes”) that seem to float over a cloudy blue ground; or her fascination with the space program, as in Jupiter’s Glow, circa 1974, which suggests the planet’s orbiting satellites with navy and chartreuse lines laid precisely against an intensely saturated scarlet field. The show also includes March on Washington, 1964, an abstracted crowd scene that commemorates the famous 1963 Civil Rights rally, in which she herself participated. (The image became a United States Postal Service stamp in 2005.)

Approaching Storm at Sunset, 1973 (detail)

Aside from this work, which prompted a brief return to representation, Thomas was a steadfast abstractionist, in contrast to what many would have expected from her in those days. During the Civil Rights movement, observes Michael Rosenfeld, the gallery founder, “the African-American artist was expected by his community to be painting works about African-American life,” with the aim of promoting change or pointing out injustice. “It took a tremendous amount of courage and perseverance for an African-American of that generation to go against that tendency and choose the path of abstraction,” he says.

But Thomas was always independently minded. Born in 1891 in Columbus, Georgia, she was the first graduate of the fine arts program at Howard University, a historically black institution in Washington, D.C., where she painted and sculpted in an academic style. By 1925, she had secured a position at Shaw Junior High School, in the same city, teaching fine art and puppetry.

And while she never pursued a painting career seriously until her retirement, she deliberately stayed single to keep her focus. She explained that decision to the New York Times in 1972, in a profile published at the time of her Whitney exhibition: “What man would ever have appreciated what I was up to?”

With the exception of brief forays into representational work, Thomas was largely devoted to abstraction, as seen in, from left, Evening Glow, 1977; The Azaleas Sway With the Breeze, 1969; and Jupiter’s Glow, ca. 1974. Photo by Matthew Newton

Visit MICHAEL ROSENFELD GALLERY on 1stdibs