May 8, 2022While I was living in Paris in the 1980s, when I thought about Art Deco, I envisioned the French treasures of the 1920s: exquisitely crafted macassar ebony cabinets by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, Jean Dunand’s eggshell-and-lacquer vases and the shimmering gold-and-silver eglomise maritime panels Jean Dupas designed for the Normandie ocean liner.

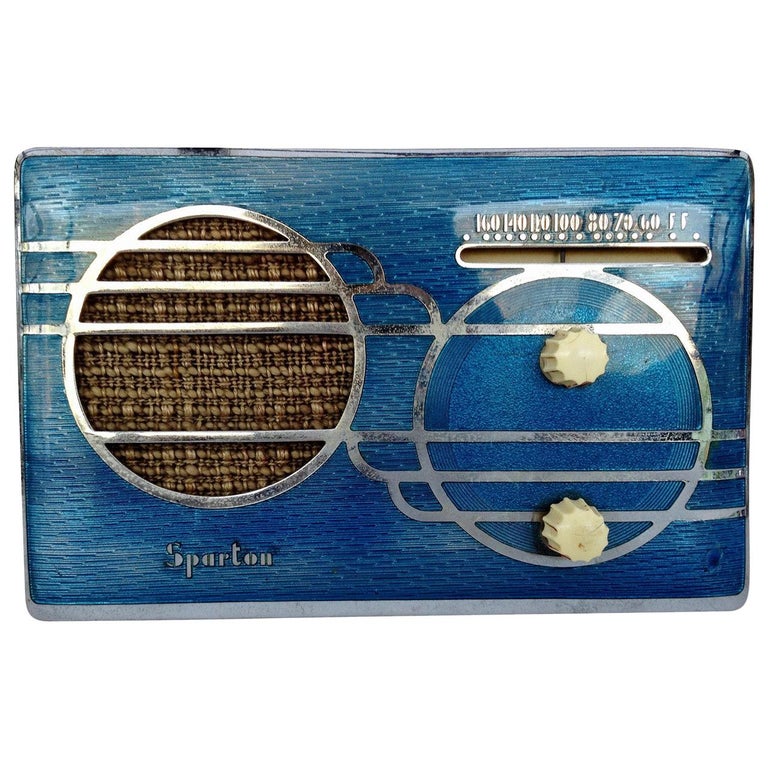

The traveling exhibition “American Art Deco: Designing for the People 1918–1939” is another kettle of fish. It comprises more than 140 objects, most American and most made of less-expensive, industrial materials.

The show — which previously appeared at the Joslyn Art Museum, in Omaha, and the Frist Art Museum, in Nashville — is on view at the Wichita Art Museum unitl the end of May. It includes a Ford Model A car, a Warren McArthur aluminum chair, Anchor Hocking Depression glass vases, a Viktor Schreckengost Jazz plate, an Electrolux vacuum cleaner, Eva Zeisel glazed earthenware and a Paul T. Frankl Bakelite clock.

In American Art Deco, plastic replaced ivory. Aluminum, steel and chrome mimicked silver. Inexpensive woods like maple were stained to resemble mahogany or ebony. Industrial designers embraced new materials and a modern look to celebrate technological progress.

Many objects in the show, such as flapper fashions and cocktail ware, embody the optimism, glamour and escapism of the 1920s. But the exhibition also explores some of the starker realities of the interwar era.

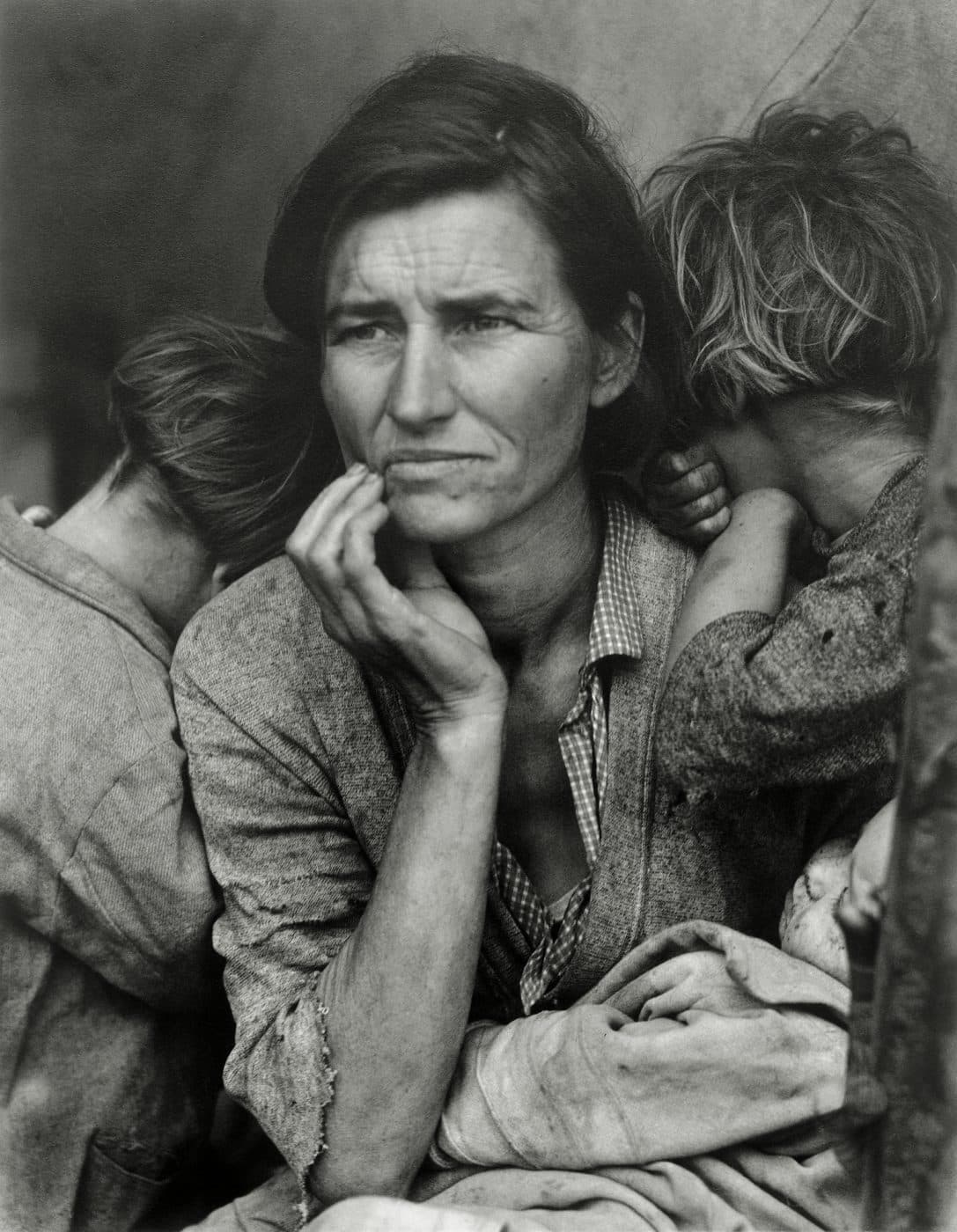

“Our idea was to not just showcase the shiny — in the U.S., Art Deco involved less-precious materials and things produced industrially,” says Catherine Futter, the director of curatorial affairs and senior curator of decorative arts at the Brooklyn Museum. Futter co-organized the show, pre-COVID, while she was a curator at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, in Kansas City, Missouri, where the exhibition will open in July. “We also wanted to focus on the more difficult sides of the story: segregation, the Dust Bowl and the Depression.”

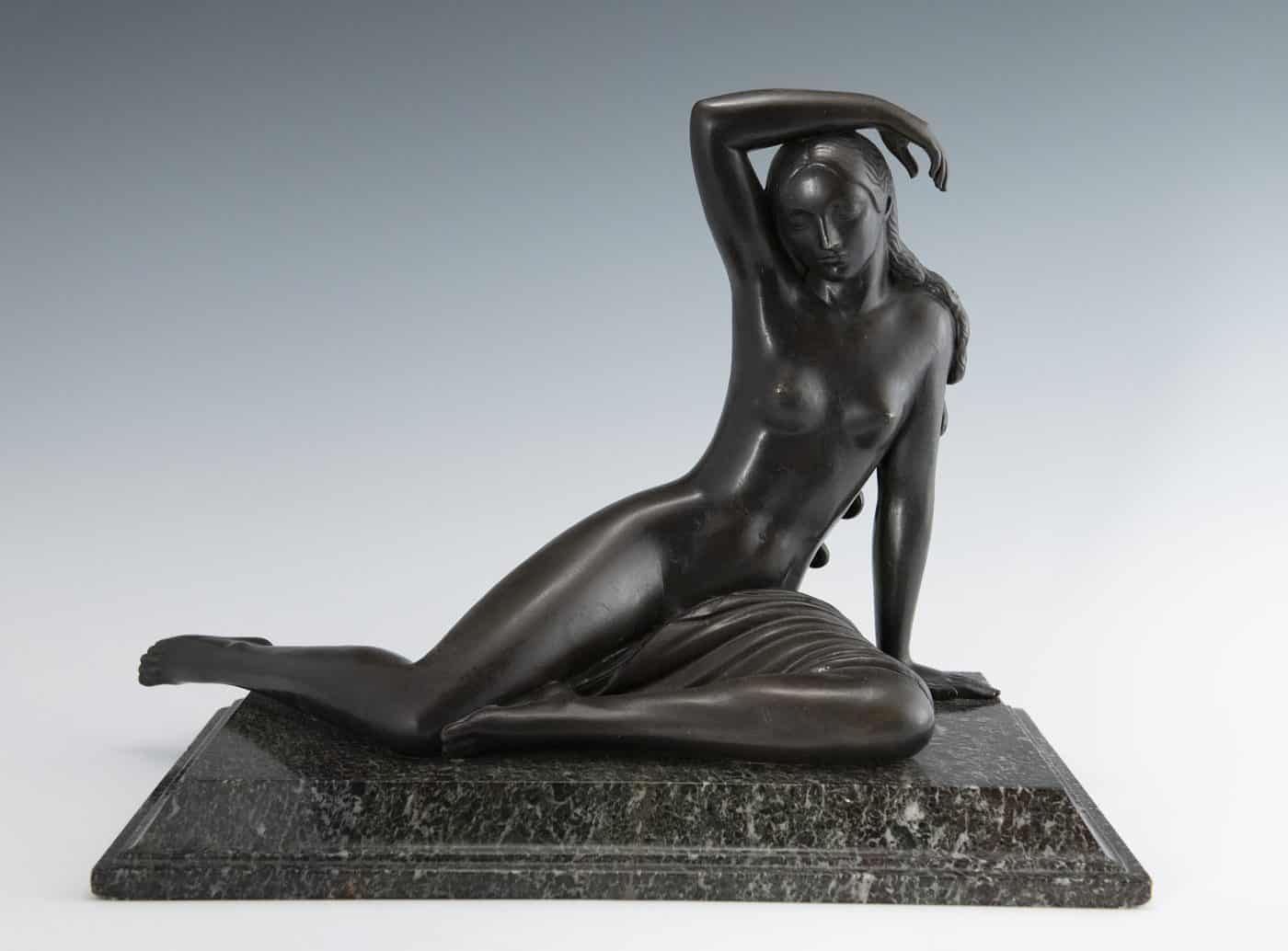

“This is not just a design show,” Futter continues. “American Art Deco is not about those luxury goods we see in Europe but about modernity and industrial progress.” Accordingly, its scope encompasses trains, planes, autos and the first skyscrapers (“cathedrals to commerce,” notes Futter). There are also sculptures, like Paul Manship’s 1920 bronze Danaë and the 1928 maquette for the aluminum sculpture Ceres atop the Chicago Board of Trade Building, an ode to the ancient Roman goddess of grain by John Bradley Storrs.

Other artworks on display include a Rockwell Kent engraving, an N.C. Wyeth ad for Fisk Cord Tires. There’s also Dorothea Lange’s iconic 1936 photo Migrant Mother.

Some pieces in the show are even more unexpected.

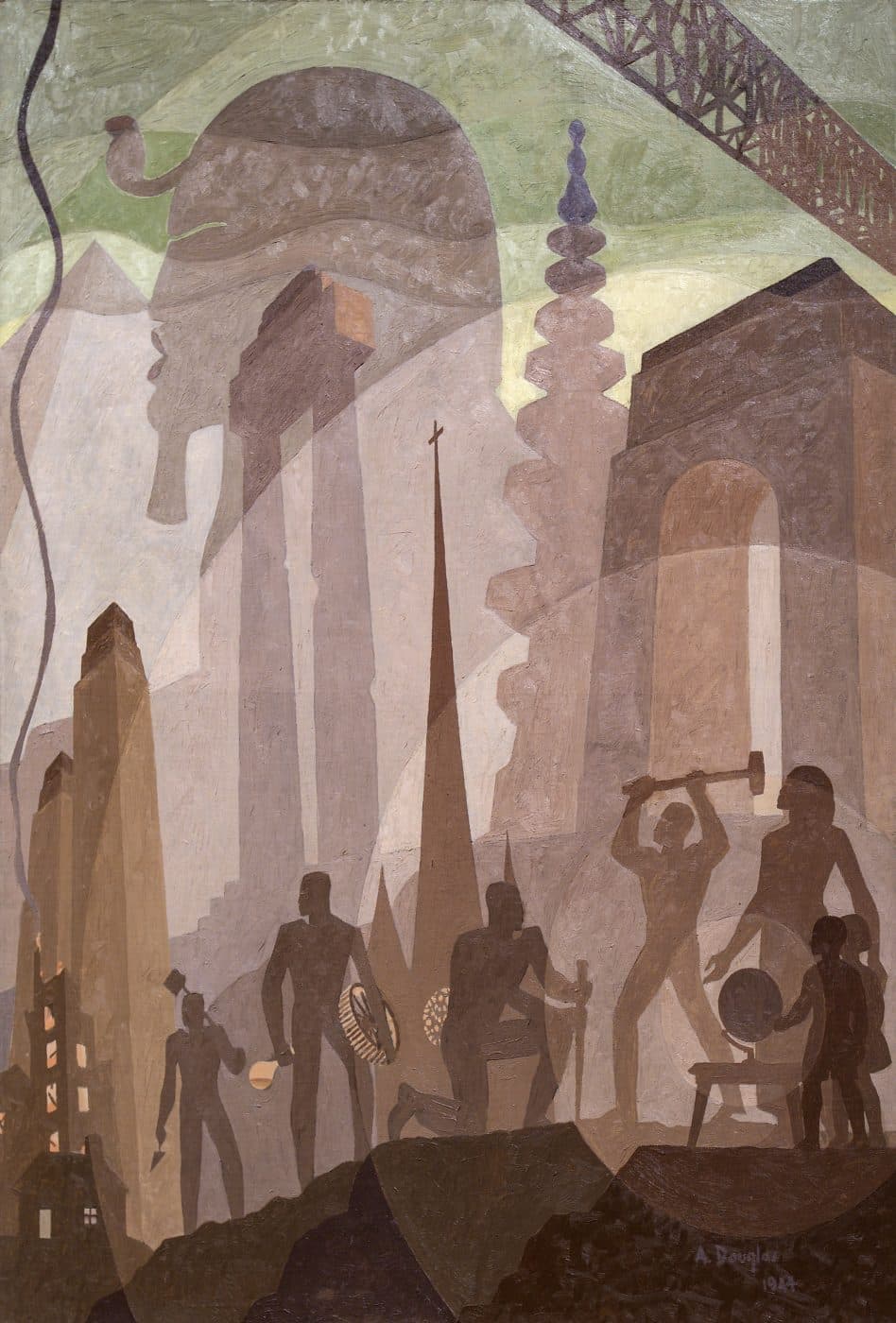

When the exhibition was in Nashville, at the Frist Museum (a Deco-style former post office designed in 1933), nearby Fisk University loaned some pictures by Aaron Douglas, a leading painter of the Harlem Renaissance. Douglas was both a talented artist and an ardent desegregationist who went on to become the president of the Harlem Artists Guild.

Fisk, a historically Black college, hired Douglas in 1944 to be the founding chair of its art department. In 1930, it had commissioned him to paint a cycle of murals in the library depicting the Black experience from the shores of Africa to life in America (the murals survive). Fisk also owns several Douglas paintings with similar themes.

The Douglas loans, which have joined the exhibition tour, are among the standouts of the show. Douglas was considered unique for fusing modernism with ancestral African imagery. His talents were recognized early. A native of Topeka, Kansas, he earned a BFA in 1924 from the University of Nebraska (where he was reportedly the only Black student) and made his way to Harlem in 1925.

In 1927, he was asked to provide illustrations for God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse, by early civil rights activist James Weldon Johnson. One of the illustrations in the show is Noah’s Ark, a multilayered picture with forms drawn from Egyptian iconography. It depicts Noah as a Black builder, his face silhouetted against the ark. Behind him, animals rush up the gangplank. Above him, a figure points to a lightning flash, signifying the impending storm and flood.

“What’s amazing is Douglas’s ability to tell the whole story in one image,” says Jamaal B. Sheats, the director and curator of the Fisk University Galleries. “He was such a skillful storyteller: You can see Noah building the ark, the animals’ arrival, the coming storm and the birds indicating nearby land. You see the whole story within one single frame.”

Another Douglas picture loaned by Fisk is Building More Stately Mansions, which takes its name from a line in the Oliver Wendell Holmes poem “The Chambered Nautilus.”

In the painting, Douglas celebrates Black contributions to architectural achievements over time, from Egyptian sphinxes and pyramids to Greek temples, Roman arches and Gothic cathedrals. In the foreground, a group of silhouetted men construct the skyscrapers of the present, wielding shovels, hammers and scientific instruments. On the right, Black children study a globe, signifying the future.

It’s significant that Douglas used the then-novel visual language of Art Deco to convey his progressive message of African-American pride and hope. The works are an important example of the many influences on and expressions of Deco style beyond Europe, and specifically in the U.S. Says Sheats, “The inclusion of these pictures in the show helps tell a fuller — though not the fullest — narrative of Art Deco in American art.”