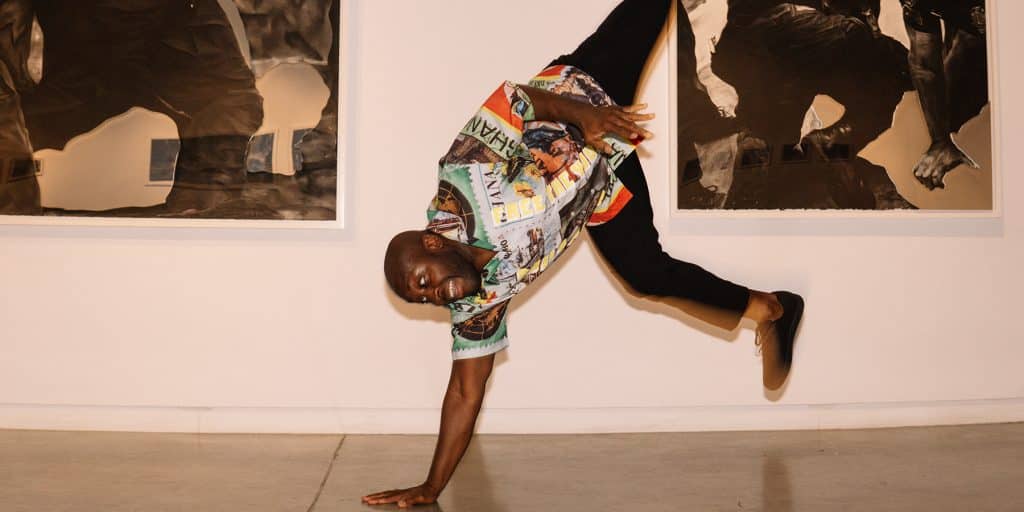

February 21, 2021Independent curator Larry Ossei-Mensah is on a mission to bring exposure to underrepresented artists who should be on everyone’s radar. A first-generation African American of Ghanaian descent, born, raised and still based in the Bronx, he’s devoted to fostering racial equity and passionate about artistic discovery. In 2013, with six friends, he cofounded the nonprofit organization ARTNOIR, an open collective that aims to support Black and Brown artists, connecting them with collectors, curators and other art enthusiasts and cultural creatives of color.

Coincidentally, that was the same year the Black Lives Matter movement started. “I would say the timing was serendipitous. You have all these things that are happening to Black people, in that moment and also historically,” Ossei-Mensah says. “And art has always been a way through.”

ARTNOIR started as a group of friends taking art field trips. “We’d go to Dia Beacon, Storm King, the Barnes Foundation,” Ossei-Mensah recalls. “And we realized that these opportunities for camaraderie were kind of missing from the art world. So, we gathered people in support of artists, celebrating Black and Brown creatives in particular.”

“We loved going on these art adventures as a community,” says ARTNOIR cofounder Carolyn “C.C.” Concepcion, “because it removed the barrier of entry presented by the intimidation and pretentiousness that arts and culture spaces often exhibit.”

Those trips engendered “an expansive vision of community, legacy building, education, celebration, joy and justice,” she adds. “We realized that the mere fact of us imagining a different perspective in the arts and showing up in big numbers — sometimes we would be thirty-plus deep — was a radical and loving act of resistance and protest, in a way.”

Ossei-Mensah’s role in ARTNOIR has largely been about the artists — building relationships and connecting the dots between them and the rest of the organization. His other curatorial contributions to the field are vast, ranging from a 2019 project on Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s work for the first-ever Ghana Pavilion at the Venice Biennale to a public art installation in celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day last month at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, where he’s curator-at-large. That work, Let Freedom Ring, alternated video pieces by seven prominent Black artists — including Derrick Adams, Lizania Cruz, Hank Willis Thomas and Jasmine Wahi — on BAM’s electronic billboard.

While Ossei-Mensah has collaborated with some of the most established artists of color working today, he’s also kept tabs on a younger generation of emerging talent. He’s got a sharp eye for exceptional work of all types and has visited studios across the world in search of it.

“I look for creativity and uniqueness of voice and materials,” he says. “I ask myself, ‘Do I feel it in my soul? Does it make me think? Does it put knots in my stomach? Or get me super pumped? Or force me to do some research that I wasn’t aware of?’ ”

But he’s also well aware that even if an artwork hits all these marks, it takes far more for its maker to thrive in the contemporary art world. “A strong community is paramount to the success of an artist,” he says. “You need to have people you can call to support you. That’s where ARTNOIR comes in.”

As ARTNOIR has grown, so have its philanthropic ambitions. This past summer, it launched the Jar of Love Fund, a grant-making initiative conceived in response to the pandemic’s devastating economic toll. “As soon as we started seeing the layoffs and the furloughs, we were like, all right, how do we help our people in need,” Ossei-Mensah says. “Instead of doing social gatherings, we reinvested in the community.” They raised more than $100,000 through a charity auction, which they then donated via micro-grants to artists and cultural professionals.

To support ARTNOIR’s mission, this February, 1stDibs is donating to the organization 15 percent of final sales from every item sold in our Black History Month collection. Called “A Legacy of Black Artistry,” the collection includes a wide variety of creators, from Sam Gilliam and Stanley Whitney, who hail from the rich tradition of Black modernist abstraction; to Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden and Faith Ringgold, three of American art history’s greatest visual storytellers; to the highly accomplished contemporary art stars El Anatsui, Martin Puryear, Mickalene Thomas and Kara Walker, among others.

No one takes a salary at ARTNOIR, whose founding partners also include Danny Baez, Jane Aiello, Melle Hock, Isis Arias and Nadia Nascimento. “This is not a job — it’s a passion,” Ossei-Mensah says.

Field trips to museums and art spaces remain central to ARTNOIR’s program. Last month, the group worked with the Bronx Museum of the Arts to do a walk-through of “Sanford Biggers: Codeswitch,” a presentation of the artist’s extraordinary politically charged, antique-quilt–based abstractions.

“The lack of hospitality that a lot of galleries and institutions have is what makes those experiences off-putting to some people. Anytime we do something, we’re welcoming, no matter who you are, as long as you come with the right energy and positivity.”

The excursions have expanded to include gallery walks, curator-led art fair tours (Frieze, Miami Basel) and yearly visits to MFA student shows. Over the years, ARTNOIR has also hosted conversations with artists like Mel Chin and Jordan Casteel; panels with prominent cultural voices, such as the award-winning Ghanaian novelist Yaa Gyasi and artist Toyin Ojih Odutola; and festive art-centered social gatherings, including a Frieze Los Angeles brunch, an annual pool party and a yearly Holiday Brunch, which raises money to fund philanthropic initiatives and ensure that the organization’s other events can remain free to the public.

Ossei-Mensah’s devotion to artistic activity is the result of an atypical route to the art world — via a master’s degree in marketing and hospitality management from Les Roches in Switzerland.

“That experience really amplified my interest in art. I was able to take the train to Milan and Paris and London to see how they deal with Black and Brown people and how the arts function there. I remember going to the Uffizi Gallery, in Florence, and looking at these blackamoor sculptures, and no one was able to explain them to me,” he says, referring to the early modern Italian tradition (that still persists) of depicting Black people as stylized, decorative objects. “I’m thinking, ‘All right, what’s really happening that I’m not privy to? And what can I do to kind of reshape that narrative?’ ”

His studies at Les Roches were also formative. “The work we do at ARTNOIR is not just about community — it’s about hospitality. The lack of hospitality that a lot of galleries and institutions have is what makes those experiences off-putting to some people. Anytime we do something, the first thing you’ll notice is that we’re welcoming, no matter who you are, as long as you come with the right energy and positivity.”

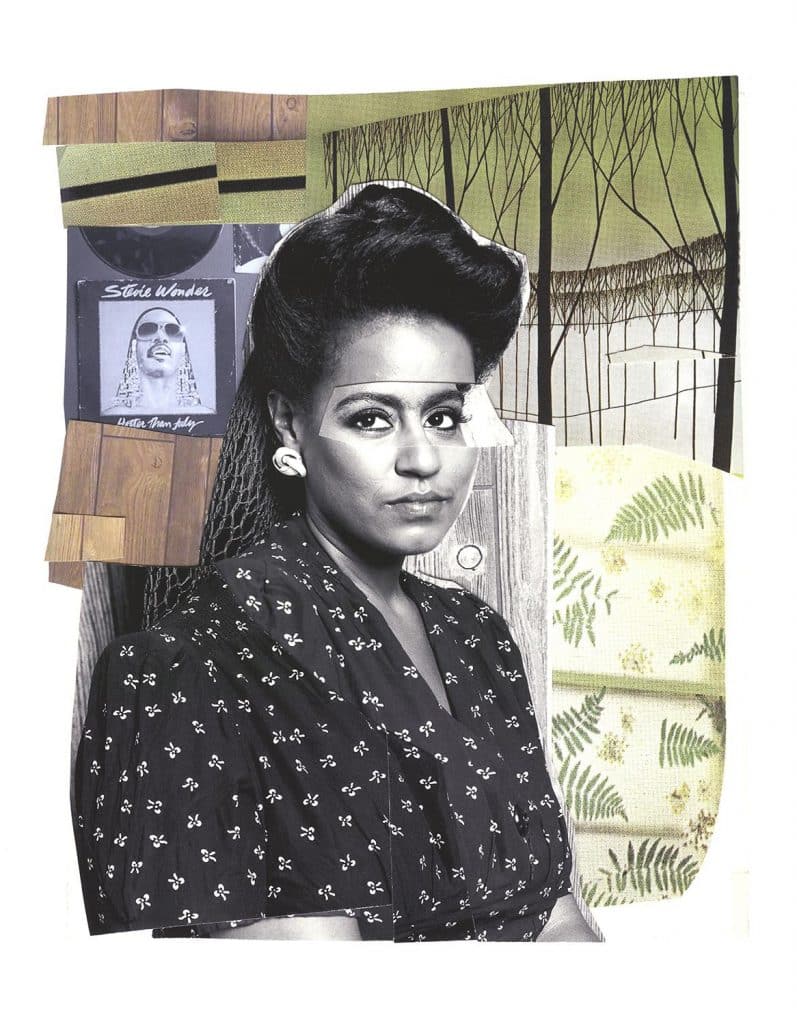

Last March, when the pandemic put an end to large social gatherings and live events, ARTNOIR adapted without missing a beat — and then kicked into high gear. It had just introduced a new online content series called Four Images, in which Black collectors are invited to share four works they own by artists of color (Bernard Lumpkin was an early participant), and soon added to the lineup weekly “Virtual Visits” inside different artists’ studios, streamed through Instagram Live.

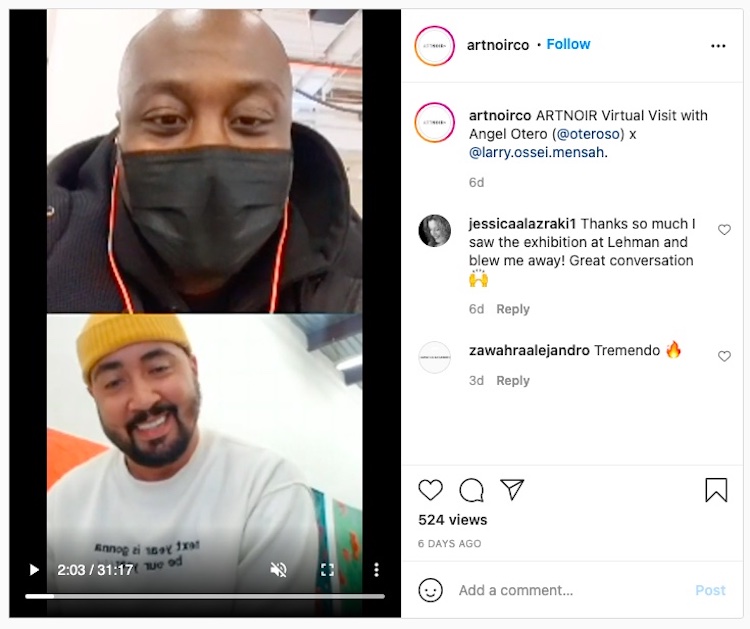

In the ongoing series, viewers get treated to highly personal half-hour artists-led tours and Q&As, sometimes with sneak peeks of new work. In a recent visit, Ossei-Mensah chatted with Puerto Rican–born artist Angel Otero, who opened up about his recent purchase of an 1867 church/studio in Upstate New York and discussed the diaristic drawings and colorful paintings of interiors that are now on view in his show “The Fortune of Having Been There,” at Lehmann Maupin in Manhattan through March 27.

“The flavor and texture of ‘Virtual Visits’ is what ARTNOIR is. It’s about intimacy, it’s about the artist’s being able to share,” says Ossei-Mensah. “People talk about ‘leveling up.’ For us, it’s leveling out, extending our reach. Artists see the visits and in turn recommend other artists to us.”

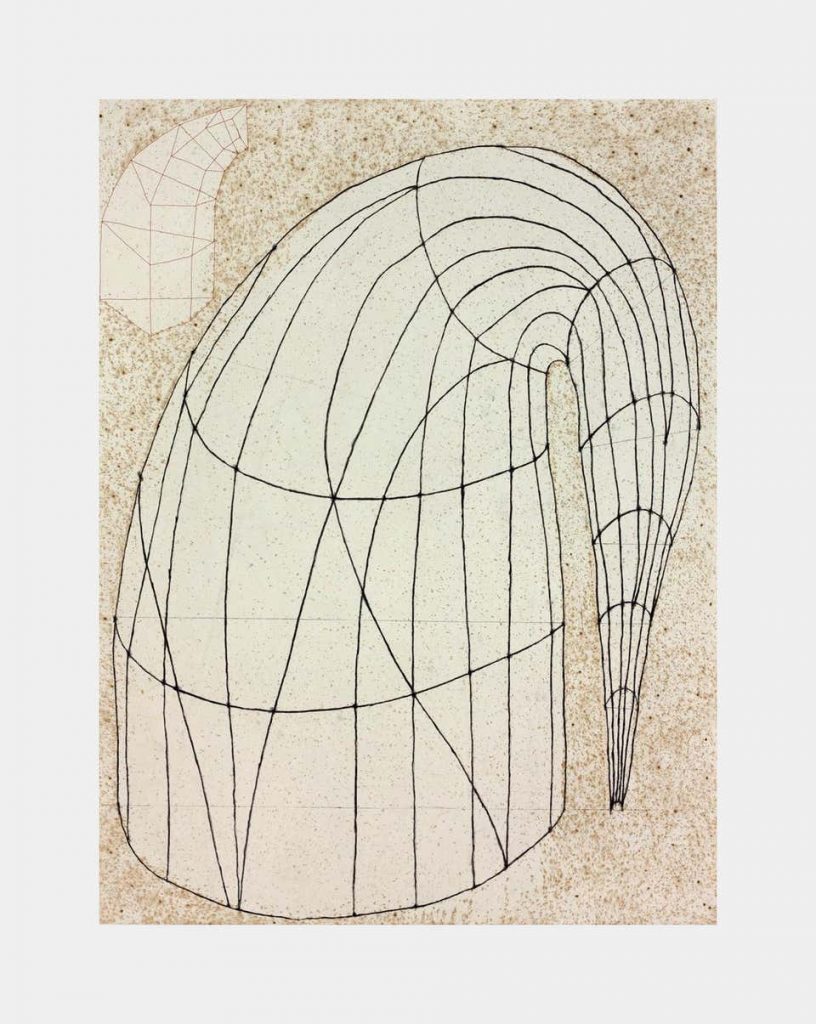

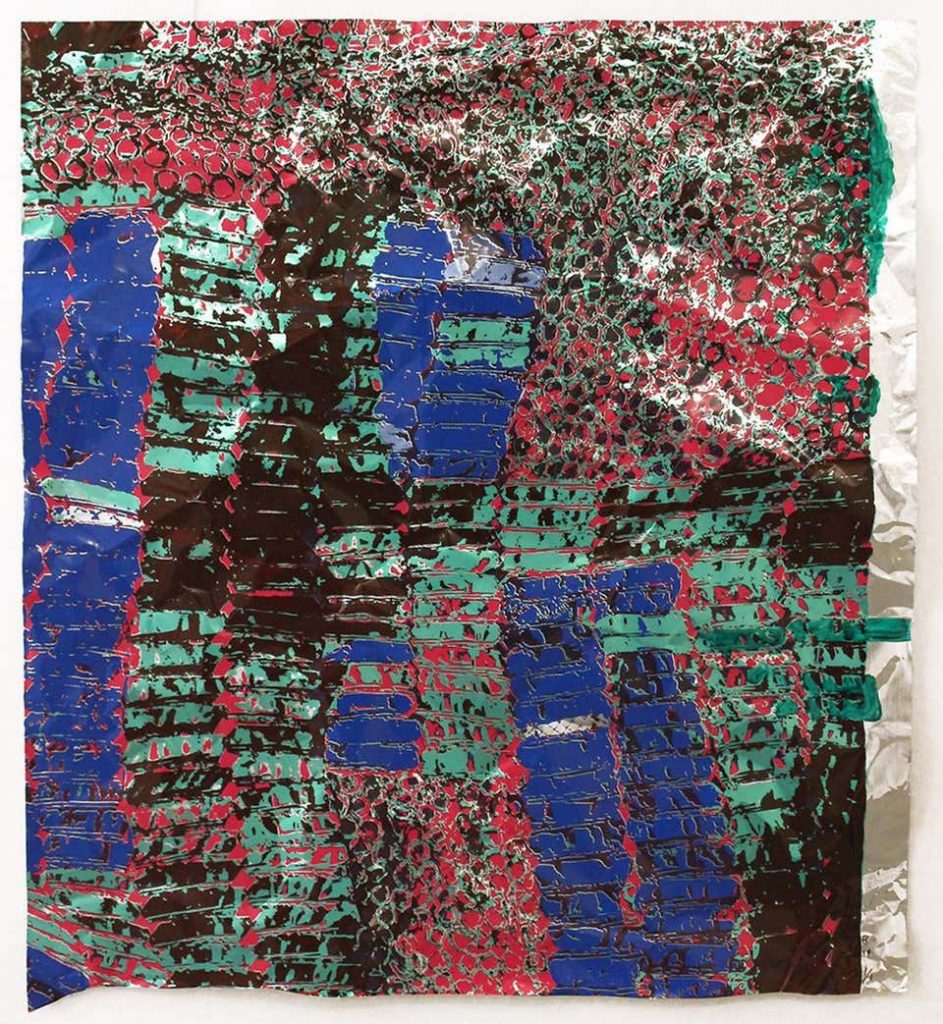

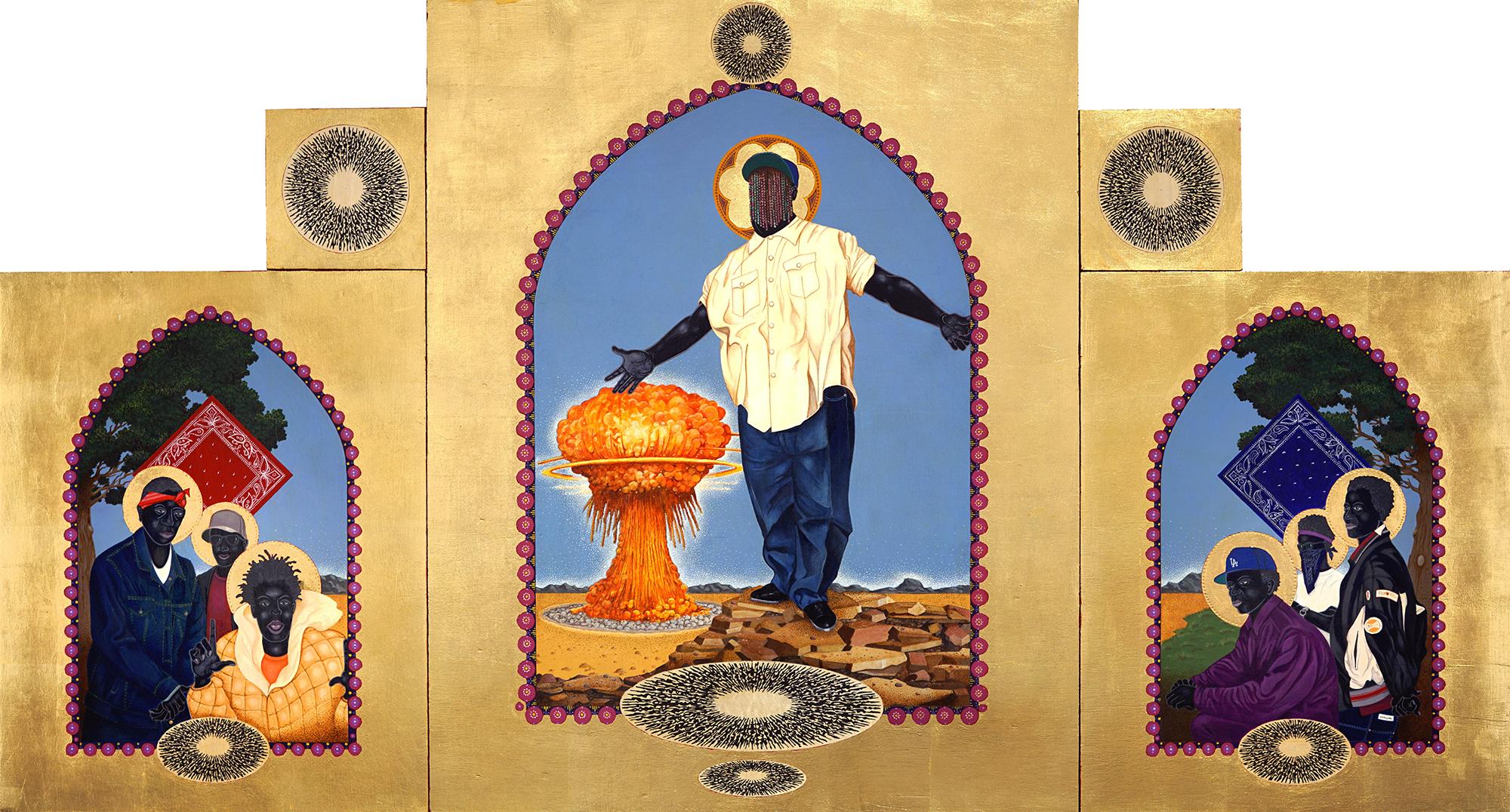

In December, ARTNOIR extended its reach further through a major new initiative, the AN12 — a recognition of achievement bestowed on 12 Black and Brown artists hailing from different points around the world, including Cameroon, Ghana, the United Kingdom, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C.

Many of the artists honored are figurative painters, although the selection reflects the variety of approaches being taken to update the traditional format. “That’s what is moving the needle right now,” Ossei-Mensah says. “But I think that’s also something we are conscious of, in terms of making sure that we are celebrating the spectrum of Black activity.”

Aya Brown’s recent portraits of Black female essential workers, exquisitely drawn in colored pencil on brown craft paper, convey a unified front of invincibility, even as the artist subtly reveals each figure’s individual character. The abstract brushwork of self-taught L.A.-based painter Greg Breda gives his portraits an expressive edginess, while Johannesburg-based Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi uses a crisp, hard-edge style to depict candy-colored scenes of Black girls participating in gymnastic competitions — a subject whose history she’s researched.

For the ARTNOIR team, it’s all just the beginning. “We would love to have a physical space where we can build and host an artist residency program,” says cofounder Isis Arias. “We have program strategies for events and experiences that will target students and children, and we definitely want to continue to build more relationships that will allow us to amplify and empower artists of color through all mediums, from visual art to performance, theater, film and more.”

Adds Ossei-Mensah, “We’re also hoping to launch a scholarship program this year — for Black and Brown MFA students in New York’s city and state schools. There is this assumption that, just because you go to a city or state school, there are no financial strains. That’s not true.”

The group sees its recent programs continuing well into the future. “We call it the hundred-year legacy plan. So, if we do the scholarship right, it will be something that exists in perpetuity. Same with the micro-grants. We’re also thinking about other initiatives that are part of the fabric of the organization,” Ossei-Mensah says. “We’re eight years in now, which is crazy to think about. And it’s still growing at a steady pace.”