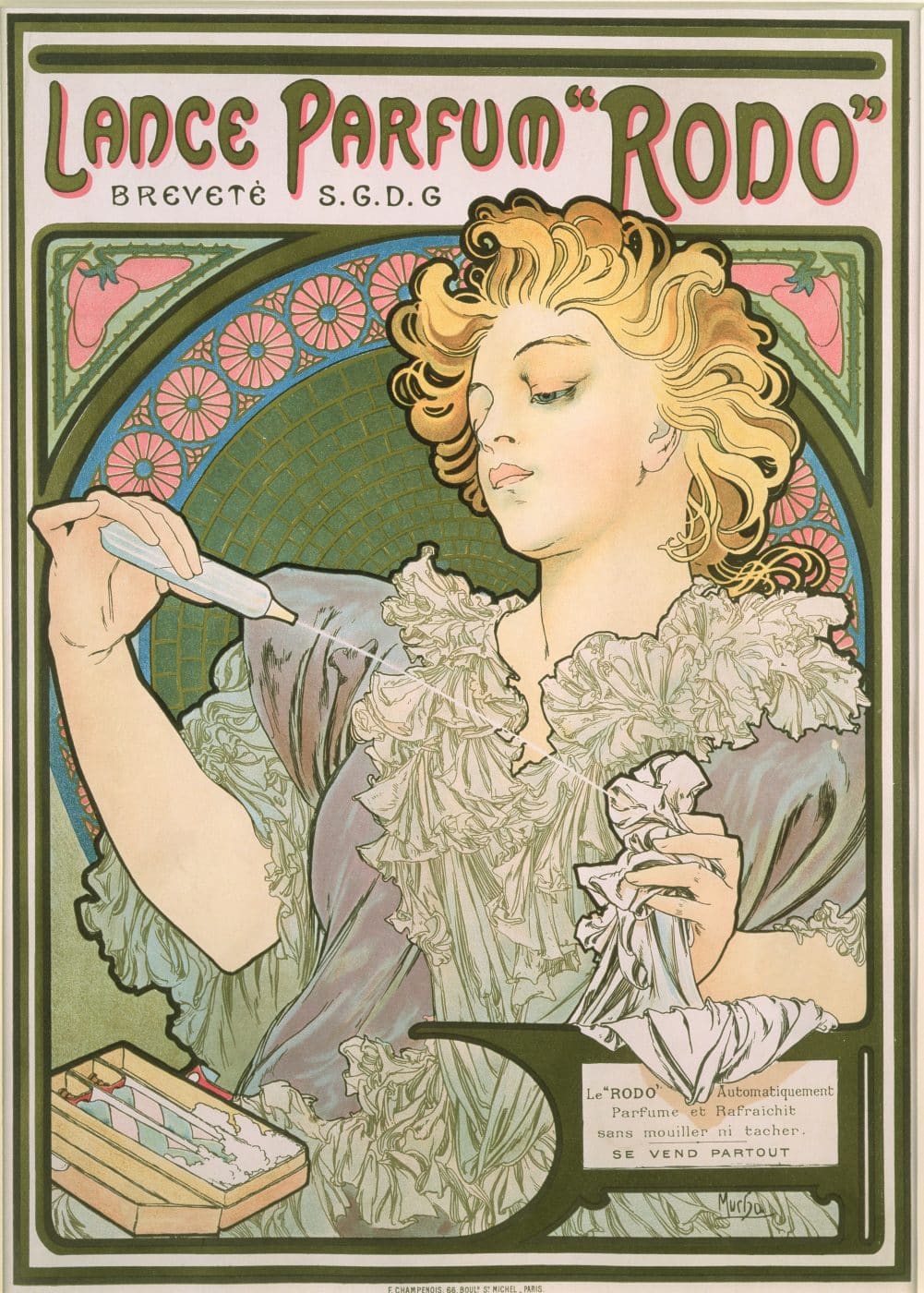

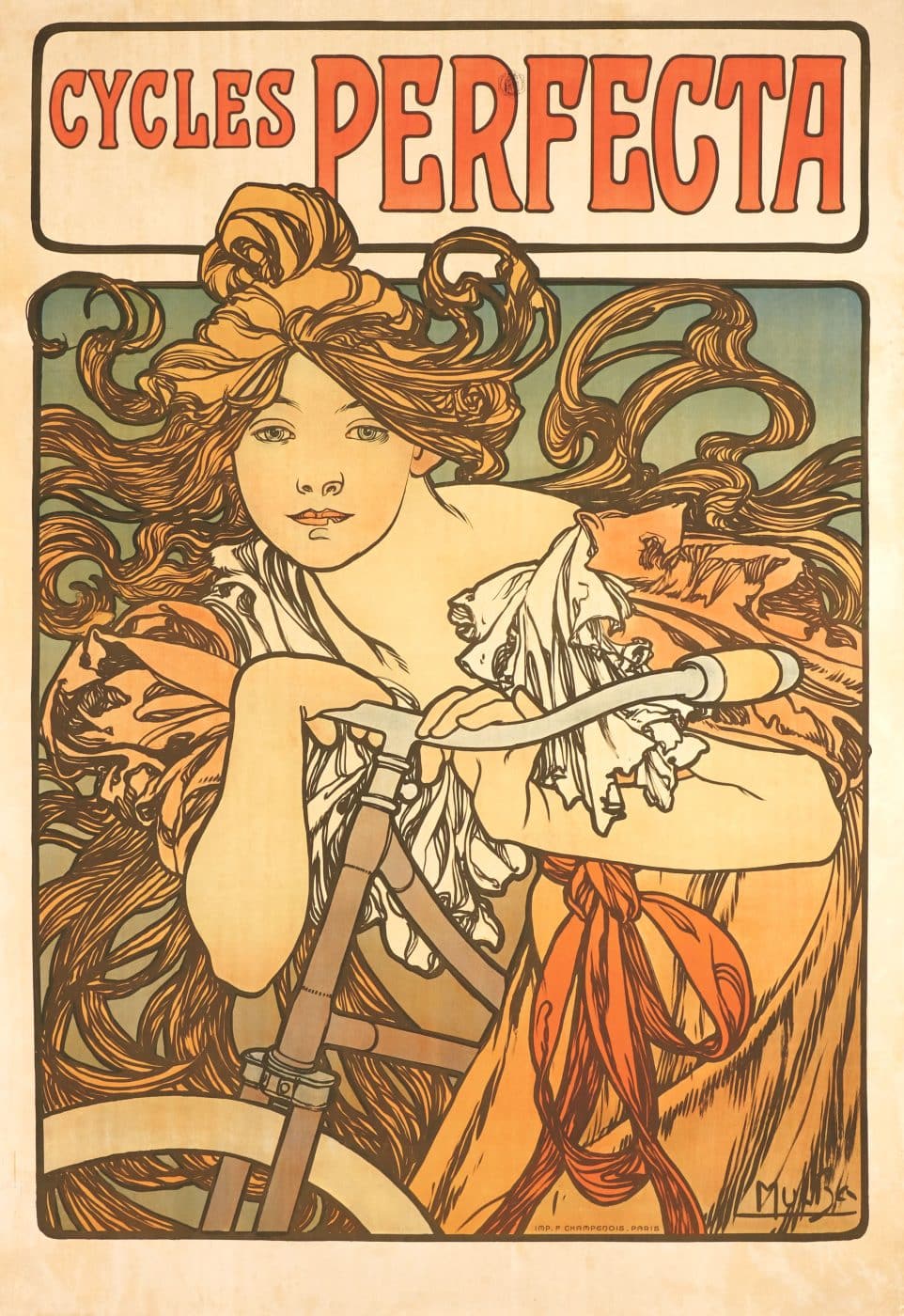

December 18, 2022If you’re at all familiar with Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939), you likely know his stylized images of garland-crowned lovelies with thick flowing locks. Posters of those haloed angels, richly rendered in pastel hues and framed with arabesques, were plastered everywhere along the streets of Paris during the early years of the Belle Époque. Beguiling heralds of Art Nouveau, they hawked everything from cigarette papers to champagne.

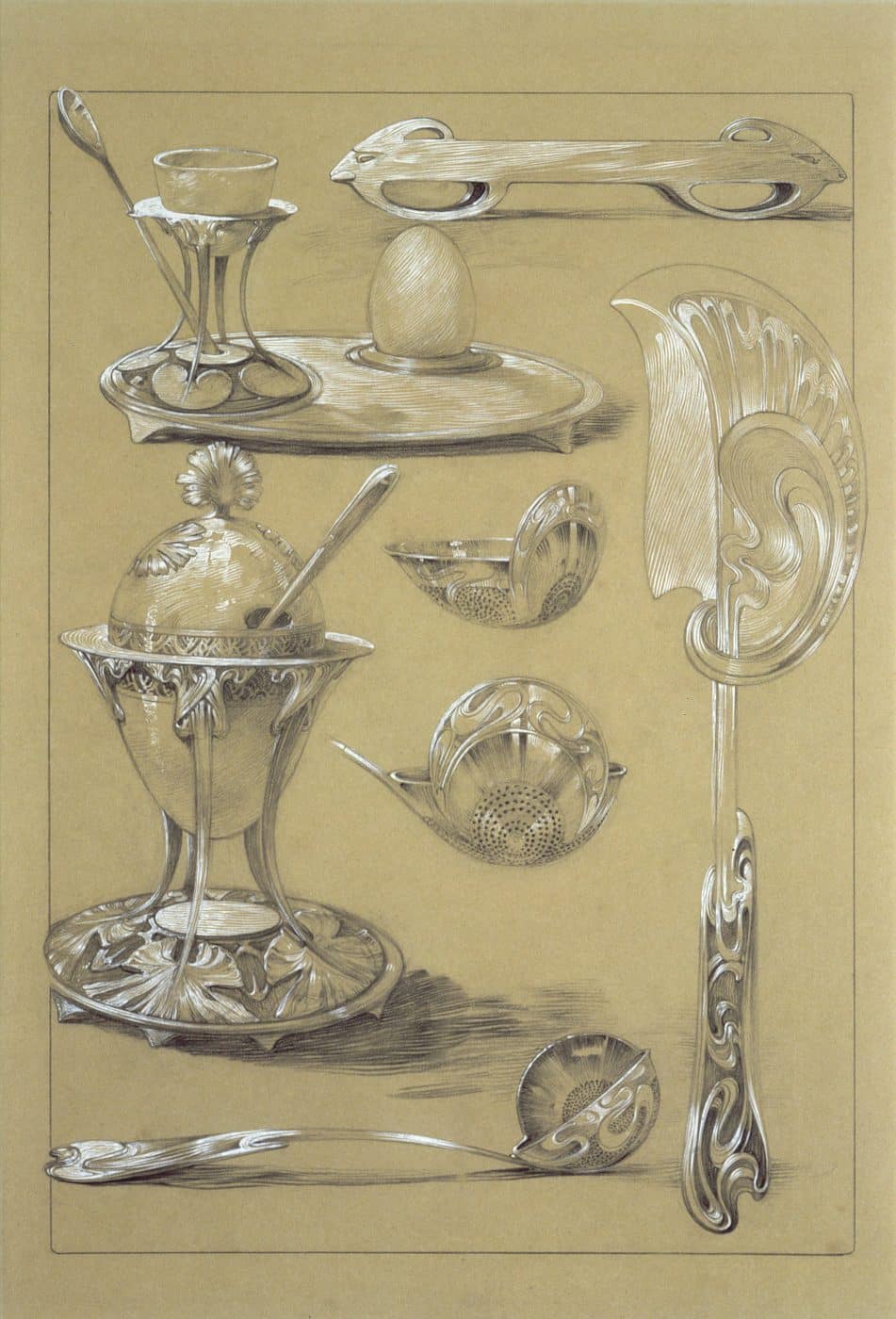

It was an extraordinary cultural moment. This nature-infused decorative style — with its many regional variations, such as Catalan modernism and Vienna Secession — gave expression to a new spirit of prosperity, progress and national identity then sweeping Europe. And Mucha, once a struggling illustrator from Moravia, part of the modern-day Czech Republic, was among its progenitors. Applying le style Mucha to the design of panels, plates, prints, decorative objects, jewelry, retail packaging, interiors and theatrical costumes and sets — not to mention teaching it in academies — he became the most sought-after artist in Paris.

Fantastic success in the commercial realm, even if achieved through wild originality, can trivialize an artist’s legacy. An artist who makes his name conjuring up fetching females can today be deemed a voluptuary, or worse. The exhibition “Alphonse Mucha: Art Nouveau Visionary” — organized by Tomoko Sato, curator of the Mucha Trust, and on view through January 22, 2023, at the Speed Museum, in Louisville, Kentucky — makes a case for the true heft of Mucha’s genius, portraying him as not only a towering artistic talent but also a high-minded thinker, a passionate Czech patriot and a deeply spiritual soul.

Drawing on new research, and through the display of more than 100 works — including rarely seen sculpture, photography and self-portraits from the Mucha family collection — the survey explores the ancient Slavic origins of Mucha’s compelling visual language, his wide-ranging artistic interests and his keen experimentation with other media.

Surprises abound. Mucha’s career in Paris was launched by a striking long, narrow poster he made of stage sensation Sarah Bernhardt in the title role of the play Gismonda, which resulted in the actress becoming his patron and close friend. Another friend was Paul Gauguin, with whom Mucha shared a studio and a fascination with traditional Breton culture, which he believed might have ancient links to the Czech Celts. He was also an intimate of Auguste Rodin, so profoundly affected by the sculptor’s art that he organized a major exhibition of his work in Prague, the most important outside France during Rodin’s lifetime. With the Lumière brothers, he experimented with film. And through his acquaintance with playwright August Strindberg, he delved into the study of Theosophy and later became a Freemason.

Mucha’s captivation with Spiritualism and the work of Rodin and other Symbolists manifested itself in his limited-edition art book Le Pater, an elaborately illustrated, highly esoteric interpretation of the verses of the Lord’s Prayer. According to Sato, he conceived the book’s allegorical plates “as a message to future generations about the progress of mankind” and poured his soul into its making. For Mucha, this sacred invocation, so central to Christianity, had universal meaning for those on the journey to Enlightenment, which he equated with Truth and Beauty. So wary was Mucha that this profoundly personal work would be monetized that he had the plates destroyed after 510 copies were published.

Mucha’s art and design were prominently represented in an array of exhibitions and projects at the 1900 Paris Exposition, where his murals in the Bosnia-Herzegovina pavilion won him a silver medal and earned him a knighthood of the prestigious Order of Franz Josef I. Yet one evening when preparing work for the pavilion, Mucha had the disturbing realization that, as he subsequently related in a letter to a friend, his “precious time” was being spent on self-aggrandizing pursuits when his homeland — then under the domination of the Austrian Empire — “was left to quench its thirst on ditchwater.” Even worse, he felt he had misappropriated ancient Slavonic motifs for his own gain. He resolved from then on to use his artistic talents to forge a Czech national and Pan-Slavic consciousness.

Before long, he embarked on a succession of trips to the United States to raise funds for the execution of a series of works representing what in his unpublished memoir he called “the joys and sorrows of all the Slavic peoples.” In 1910, he returned to Bohemia to at last produce the 20 enormous paintings that compose the “Slav Epic,” which he completed in 1926. He wanted this historic cycle to have its own home in Prague, where he hoped the immersive experience would awaken the Slavs to their common bond and inspire them to strive for the good of all humanity.

Principled in his approach, he rendered these works not with the seductive imagery that had won him such a passionate following but in an allegorical historical style that was dated before the paint on the canvases dried. And so, alas, Mucha’s heartfelt opus failed to connect with his kinspeople, much less reflect the emerging spirit of a modern Czech nation.

That national spirit has evolved over the past century. And Mucha’s monumental work, long displayed in obscurity in a castle in Moravský Krumlov, near his birthplace, will soon have its own exhibition venue in Prague. It will be located in a new development in the historic center designed by the prolific Brit Thomas Heatherwick, due to open in 2026. It seems the time for the heroic vision of Alphonse Mucha, the Czech patriot, has finally come.