March 8, 2020The 20th-century polymath Buckminster Fuller coined the word Dymaxion (a portmanteau of DYnamic, MAXimum and tensION) to describe his futuristic visions. Over the course of his career, Fuller produced Dymaxion cars, Dymaxion houses and even prefab Dymaxion bathrooms.

So when the designer and sculptor Isamu Noguchi asked his friend Fuller for permission to use the Dymaxion name on a new product, it was no small request. What was this “very neat” device of “unparalleled efficiency” (Noguchi’s words) that he wanted to label Dymaxion?

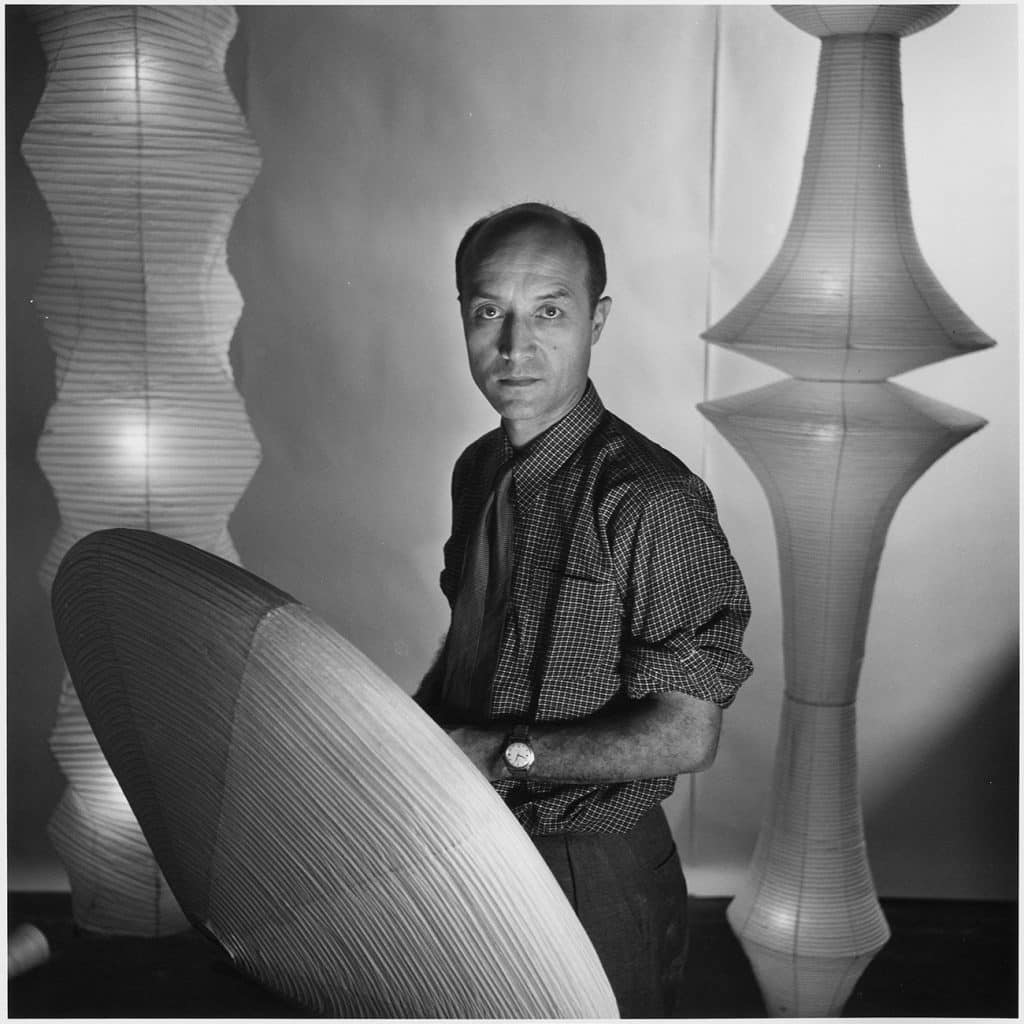

The exhibition “The Sculptor and the Ashtray,” currently at the Noguchi Museum, chronicles Isamu Noguchi’s efforts to elevate a common gadget into an efficient high-design item. Above: Isamu Noguchi, 1955, by Louise Dahl-Wolfe. Top: Clockwise from top left, Josef Hoffmann Wiener Werkstätte complete smoker’s set, ca. 1923; Vik Muniz Untitled (Wanderer Ashtray), 1999; Philip Johnson for Jenfred-Ware aluminum ashtray, 1950s; Alvaro Siza moving ashtrays, ca. 1980; Knoll standing floor ashtray, 1960s; Marc Newson ashtray, 1990s; Ettore Sottsass for Habitat Yantra 38 ashtray, ca. 1980; Warren McArthur smoke stand smoker, ca. 1935.

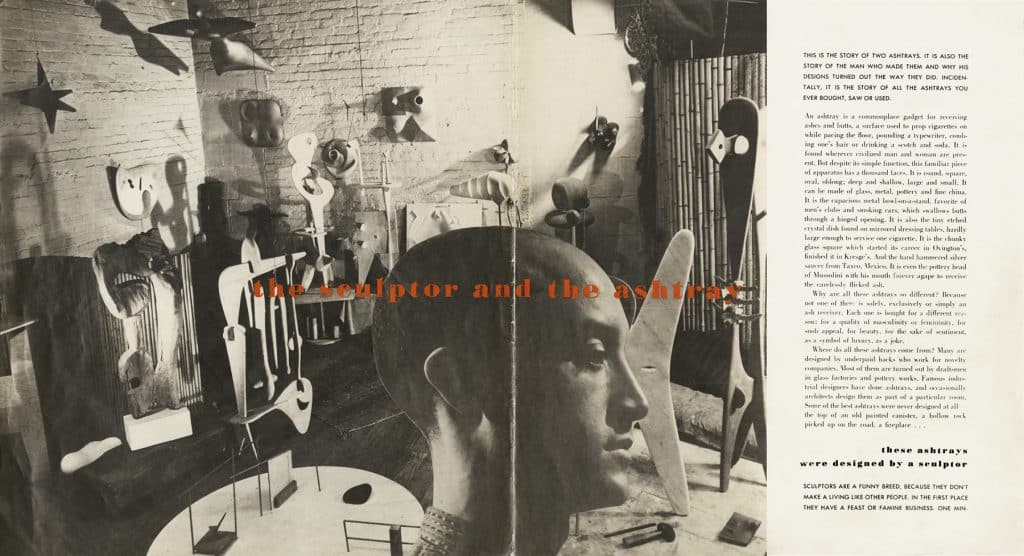

An ashtray. Yes, an ashtray, then a near-universal tabletop accessory — “found wherever civilized man and woman are present,” in the words of Mary Mix, who chronicled Noguchi’s ashtray project for a never-launched magazine in the 1940s. According to Mix, Noguchi had spent months working on a series of “bullets” — made of ceramic, metal or glass — spaced so that they could be used either to hold cigarettes or to extinguish them.

In a letter to Fuller dated April 18, 1945, he asked: “What I would like to know is, after you see it and like it, whether it might not be called the Dymaxion ashtray, for that is exactly what it is.”

Bullet ashtray design by Isamu Noguchi, pictured in “The Sculptor and the Ashtray,” an unpublished magazine article by architecture and design writer Mary Mix, ca. 1944. Photo courtesy of the Noguchi Museum Archives, ©INFGM / ARS

Noguchi’s ashtray, which turned out to be too difficult to mass-produce, is featured in the show “The Sculptor and the Ashtray,” at the Noguchi Museum in Long Island City through August 23. The exhibition also chronicles his efforts to form a very different kind of ashtray out of plaster.

Noguchi was hardly the only important designer (or artist) of the 20th century to devise ashtrays, and the Noguchi Museum is hardly the only institution to show them. Ashtrays may have outlived their relevance in many people’s lives but not their relevance to design history.

As the museum’s senior curator, Dakin Hart, notes in his catalogue essay for the show, “This ‘commonplace gadget’ was made and used across the full spectrum of material culture, from tacky novelty items and marketing swag designed by unknown ‘hacks’ to solid-gold objets d’art conceived by the great artisans of the day for the coffee tables of monarchs.

“Like the chair,” he continues, “which is so often regarded as an essentialist encapsulation of the values of the societies and designers who have — or have not — produced them, the ashtray’s ubiquity made it an inherently fascinating prism for revealing cultural values.”

Left: Max Huber for Arteluce ashtray, 1960s. Right: Georges Jouve and Mathieu Matégot yellow ceramic ashtray, ca. 1950.

Ashtrays are in a category of products that Ulysees Dietz, a longtime decorative arts curator at the Newark Museum, calls the “accessories of sin.” These objects — related to smoking, drinking, gambling and other vices — “have traditionally been designed and made with as much care as any other artifact associated with elegant living,” he says, citing a modernist cocktail shaker and a craps table once owned by “a Louisiana nightclub with a checkered past” as proof.

In fact, a history of ashtrays is a history of modern design, with all its currents and cross-currents. In 1924, Marianne Brant, director of the metal workshop at the Bauhaus, in Weimar, Germany, designed a geometrically succinct ashtray of tombac, a copper-zinc alloy, that is now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Around the same time, and just a few hundred miles away, Josef Hoffmann, the Wiener Werkstätte founder, produced an ornate brass smoking set, including ashtrays and cigarette and matchbox holders. A few years later, Josef’s son, Wolfgang, who had emigrated to the United States, and Wolfgang’s wife, Pola, designed a modernist ashtray, later acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In the postwar years, the democratization of luxury led to an explosion in the number of well-designed ashtrays. (It’s no coincidence that Noguchi devised his “Dymaxion” version, which he hoped would make him rich, in 1945.). The design collection of the Museum of Modern Art includes ashtrays by Carlo Scarpa (Murano glass, 1950-59); Trudi and Harold Sitterle (glazed porcelain and black oxidized steel, 1951); Achille Castiglioni (stainless steel with spring-like inserts, 1970); Masayuki Kurokawa (rubber and steel, 1973); and Philippe Starck (polished aluminum, 1986).

In 1995, Marc Newson was commissioned by the Swedish tobacco company Blend to design an ashtray. The result, a circular glass vessel with grooves machined into its rims, is perhaps one of the last ashtrays by a prominent designer.

Spread from Mix’s unpublished magazine article “The Sculptor and the Ashtray.” Image courtesy of the Noguchi Museum Archives, ©INFGM / ARS

Smoking declined in popularity in the 1970s and ’80s, after the surgeon general’s warning began appearing on cigarette packs, but designers were still crafting ashtrays through the end of the century (especially outside the United States). Not everyone, moreover, has stopped smoking. “If you know anyone under the age of thirty or over the age of fifty,” says Richard Petit, of the Los Angeles firm The Archers, “you probably know a smoker, or an evening-only smoker, or an only-with-drinks-in-the-evening smoker. Or, of course, a pot smoker. So, you really need to have at least a few handsome ashtrays on hand. Otherwise, you’ll be offering your smoking guests a saucer. And that just isn’t good enough.”

Some designers like the message ashtrays send. Fawn Galli, of New York’s Fawn Galli Interiors, says a few strategically placed ashtrays “set the stage for a party. They signal the possibility of ignoring rules and reason and just having fun.” Others turn to them for more practical reasons. “I love vintage ashtrays and still use them in my home,” says the Manhattan interior designer Bella Zakarian Mancini. “No, we don’t smoke, but I do burn incense and palo santo and find them very useful for keeping the house from burning down.”

From left: Eero Saarinen for Knoll International set of nine white tulip ashtrays, ca. 1970; sculptural ashtray, 1950; Fornasetti for Winston ashtray, 1980s.

What distinguishes ashtrays from mere bowls or saucers is grooves, or other devices, for holding cigarettes in place. In some cases these are subtle; in others, they are significant design features, like the wire cigarette holder of the Eichler Goodman copper ashtray, which becomes a sculptural element. Also in that camp are Max Huber’s ashtray for Arteluce and a 1960s Viennese hedgehog. Not surprisingly, the endlessly inventive artist Alexander Calder created numerous ashtrays, including one made from a can, its top cut into strips that splay out like flower petals to become cigarette holders.

Some ashtrays are small tabletop items, unprepossessing in form but bearing charming surface treatments, such as Piero Fornasetti’s and the ones Emil Antonucci designed with the logos of the legendary Four Seasons restaurant. A limited-edition ashtray by the great Brooklyn-Brazilian artist Vik Muniz bears the image of a standing figure seemingly rendered in ash.

Alexander Calder ashtray, ca. 1940. Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s

Some tabletop ashtrays are more formally inventive. Philip Johnson created a model made of concentric circles. And he was far from the only architect — or Pritzker Prize winner — to tackle ashtray design. Alvaro Siza crafted a set of Moving ashtrays, so named because they rock on nearly spherical bases. “Ettore Sottsass was another star designer who reinvented the form, even making sculpture out of a ceramic cigar ashtray. (Cigars and pipes require their own specialized accessories.)

An image of plaster Noguchi ashtray prototypes, ca. 1944, hangs above iron Bonniers bowls/ashtrays in the exhibition. Photo courtesy of the Noguchi Museum

The Danish designer Arne Jacobsen devised the rare ashtray that can be called iconic: Cylinda (1964-67) consists of a stainless-steel bowl that flips over to deposit ashes in its cylindrical base.

In addition to the tabletop versions, there are also standing Cylindras — pieces of furniture sometimes called smoking stands. Warren McArthur designed a smoking stand in his signature industrial-deco style. (Also by McArthur: chairs with ashtrays hidden in their arms.) The simplest smoking stand may be the elegant cylinder model from Knoll. Eero Saarinen, himself part of the Knoll stable, designed tulip ashtrays with the same familiar curves as his tulip tables and chairs

Sometimes, ashtrays are parts of larger pieces, as in the stunning leather-wrapped-iron stand by Jacques Adnet, which combines an ashtray, a small wooden table and a magazine rack. The great ceramist George Jouve created ashtrays that fit into humble but spirited metal stands by Mathieu Matégot (circa 1950).

Says Dietz, “As long as smoking was fashionable (and not simply tolerated as a bad habit hard to break), ashtrays were an important part of any stylish home or restaurant. Now that smoking has been relegated to back alleys and furtive corners, ashtrays have become an archaic artifact.” And like other archaic artifacts, from arrowheads to armor, their distance from contemporary life makes them objects of fascination.