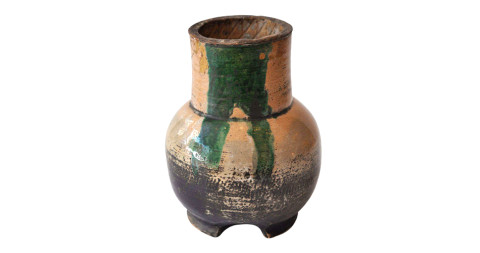

November 23, 2015Acclaimed French photographer François Halard shot his own loft in New York’s Soho, designed and decorated by his architect nephew Bastien Halard, who incorporated a custom plaster fireplace, African stools, a 17th-century Irish mirror, Diego Giacometti lamps and 1950s French ceramics.

Bastien Halard’s great-grandfather Adolphe Halard founded Nobilis, the French fabric and wallpaper company, in 1928. His grandfather Yves Halard started his own eponymous interior design firm, where he worked with his wife, the equally admired decorator Michelle Halard; Bastien spent every holiday with them, plastering their beautiful wreck of a castle, prowling flea markets around France to furnish it — “and looking at churches on the way,” he says. His mother, Florence Chabrières, is a decorator like his grandparents, and his stepfather, Jacques Freudenthal, is an architect. Then there’s uncle François Halard, the well-regarded interiors photographer.

With a pedigree like that, it’s a wonder that Bastien Halard had the nerve to consider any career besides design. Of course, when he did, his field of interest — the art world — wasn’t exactly a big stretch. Starting at the age of 16, he worked part-time for a series of galleries. When he was an architecture student in Paris, he and some friends broke into Pierre Cardin’s boarded-up former hôtel particulier to stage art shows inside.

This teenage flirtation with art was brief. “My uncle said, ‘You don’t have any money. You can’t have a gallery if you’re not rich,’ ” Halard recalls with a wry smile.

Instead, Bastien came to New York in 2004 to help François move from one apartment to another — and never left. About a week after his arrival, his uncle hosted a dinner party at which Halard met two people who gave him good reasons to stay: Daniel Romualdez, who promptly offered him a job at his architecture and interior design firm; and Miranda Brooks, a landscape designer and Vogue contributor, with whom he was instantly smitten. (They married in 2010.)

The master bathroom in the Brooklyn home Halard shares with his wife, landscape designer Miranda Brooks, doubles as a sitting room, featuring a Gerrit Rietveld pendant, a Gustavian bench and bookshelves the architect built himself. All photos of Halard’s home were shot by François Halard.

For the past dozen years, Halard has been honing his skills in New York. At 35 — just a babe in the gray-haired architecture field — he now runs Halard-Halard, a boutique studio that recently outgrew the carriage house behind his Boerum Hill, Brooklyn, townhouse where it began and decamped to Red Hook.

Tanned and boyishly good-looking, his hair casually mussed, Halard stands in the townhouse, one white Adidas-shod foot in the living room, the other in the small, lush garden, into which he blows his cigarette smoke. His dog, rescued as a starving puppy at the base of the Atlas Mountains in Morocco, is sleeping peacefully under the dining table, but Halard seems a bit harried, juggling projects in Rhode Island, the Hamptons, Paris and right here in Brooklyn, while trying to steal away to France for a holiday with his family.

“People call me when they have an original, interesting, historic building but don’t want to do some fake traditional,” he says. “One shouldn’t be building a fake seventeenth-century house in 2015.”

Before starting Halard-Halard, he apprenticed at a series of New York’s most prestigious agencies, beginning with Romualdez, a society favorite whose clients include Aerin Lauder and Tory Burch. There, Halard was charged with tracking down requested furniture. “I could tell the difference between Louis XV and XVI,” he says with a smile. “I knew Paris very well.”

The dining room in François’s loft also serves as a gallery. “I like dining rooms to be multifunctional, central,” says Halard, “to keep them alive.” Surrounded by 1940s chairs, the table is made of a pair of concrete colonnade planters and a tabletop from the 1960s. One of François’s photos of Casa Malaparte hangs behind, while above is a chandelier that belonged to Halard’s grandfather.

Next he went to work for Peter Marino, whose clients include both international moguls and luxury retailers. Halard contributed to the redesign of Dior’s grand Avenue Montaigne flagship store in Paris and again was put on the furniture beat. “Whenever there was furniture to do, it was me,” Halard says. “I love furniture.”

He was less enamored of working on a Las Vegas casino for Marino, so he jumped to Studio Sofield, where he focused on projects for Tom Ford and on a retail space in an elegant 1920s building in Barcelona. His response to the challenge back then — “How do you preserve the identity, modernize it and make it something contemporary but with the spirit it had?” as he puts it — has guided his subsequent restoration projects.

During the economic downturn of 2008, Halard worked up the nerve to strike out on his own. “In two weeks. I got offers for three different jobs — not huge jobs but big enough to start a company,” he recalls, adding with a laugh, “Of course, two didn’t go through, and I was left with just one.”

Halard initially set up shop in a cramped bulkhead, without heat or air conditioning, that he built atop his townhouse, christening the business Halard-Halard. The second “Halard” is a nod to François, with whom he hopes to collaborate one day. “He’s an absolute encyclopedia,” Halard says of his uncle.

Referring to this home on New York’s Upper East Side, Halard says, “When the furniture allows it,” — that is, when it is quality furniture — “I like to use it almost as a still life. It makes its own picture.” In this vignette, a Pierre Jeanneret sofa and low table keep company with a Pierre Guariche floor lamp.

The young architect’s first solo effort was a gut renovation of a duplex in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, for friends on a shoestring budget. As in a host of his projects since then, he sought to modernize while preserving, blending aspects of minimalism with a respect for original intent, reclaimed materials and a certain bourgeois-Bohemian flare. Many of his clients have young families and limited funds. “The least expensive way of making something nice is to keep the charm of it,” he says.

His style is on full display in the townhouse he shares with Brooks, a frequent collaborator, and their two young daughters. There, he dispensed with upper cabinets in the kitchen in favor of art, exposed the rafters, painted the wood floors, built a hutch for the pet rabbits on the roof and devised a kind of combination bathroom–sitting room for the master suite. He also fashioned his and Brooks’s dramatic headboard from a tree trunk and tapped his friend the Brooklyn-based artist Hugo Guinness to draw on the master bedroom doors.

Halard freely mixes periods: a modern bed, 17th-century drawings, a vintage tub, contemporary art. And he does the same when it comes to the placement of art, hanging some paintings and drawings in obviously “wow” spots, hiding others low on walls or in nooks. “I’ll put them somewhere secretive, and you’ll have to be sitting down. You’re experiencing them in a different way.

“I’m not an expert in contemporary art, I’m not an expert in eighteenth-century painting, but I know about it all enough to be able to balance,” he adds.

“People call me when they have an original, interesting, historic building but don’t want to do some fake traditional.”

In an artfully but informally composed room in the former Kentshire Galleries building, Halard combined a Jeanneret armchair, Axel Vervoordt sofa, Moroccan rug, Willy Rizzo coffee table and Angelo Mangiarotti side table. The curved oil painting is Perogative, 1987, by Ron Gorchov.

Halard laments that many of his lovingly produced spaces have been marred by inferior furniture — “crap,” he calls it — from such offenders as IKEA and Restoration Hardware. “Architecture is easier in a way, because people don’t pretend to know [about it]. They trust you,” he says. “When it comes to decorating, they have their opinions.” If the client is willing to invest in serious furniture design, Halard is happy to help, although he admits that when he launched Halard-Halard, he wasn’t too keen on decorating gigs. “I was pretty reticent for a bit to do decorating, because I just couldn’t face doing cushion colors,” he says.

Now, he feels established enough as an architect to take on interiors as well. A recent project, in fact, highlighted his keen knowledge of furniture. New York developer Edward Minskoff tapped Halard to hunt for prime pieces from both big-name and emerging designers for a new collection that Minskoff installed in the model apartment at 37 East 12th Street, the former Kentshire Galleries building, which he has transformed into luxury condominiums. “It was great fun,” says Halard, whose choices ranged from 1950s and ’60s Dutch designs, which he calls “undervalued,” to a “perfect” museum-quality, circa 1954 Antony daybed by Jean Prouvé and Charlotte Periand. “A lot of it wasn’t obvious.”

“The least expensive way of making something nice is to keep the charm of it,” says Halard, summarizing one of the guiding principles of his aesthetic.

Among Halard’s other current big projects are a gut renovation of a West Village townhouse, including the addition of a very contemporary penthouse and glass-box rear extension; an overhaul of the Bonpoint children’s clothing boutiques and visual identity; and his first ground-up house, on a private island off the Hamptons, where Brooks has already created the pool. He is also renovating four existing buildings there, one of them an early-19th-century farmhouse that he’s moving to another site on the island. In its place, he is erecting the new house, whose design was inspired by early Shaker architecture, which he calls “so minimal and modern in a way.”

“It’s interesting, because there is a language on the island of old wooden clapboard houses, which I want to respect,” Halard says. The new structure is tall and narrow, like a chapel, with single-pane windows. It will be a relatively modest 4,000 square feet. “I always try to reduce houses as much as possible. I believe every space has its own use, and if you have one great big space, you shouldn’t need ten of them.” He has a distaste for McMansions, explaining, “Architecture is proportionate to the landscape when it comes to country houses.” And he is not a fan of increasingly ubiquitous fully open-floor plans, preferring instead to create transitions between defined spaces: “Visually, you see through, but I’m breaking the space.”

As he develops professionally, Halard insists he is determined not to “just make an architecture statement, just to be a pretentious architect,” but rather to find unique solutions for every project. “Each house has its own potential,” he says. “My role is to look at what’s good, what’s right — and what’s not right.”