February 2, 2022If there is one thing that Darryl Westly values above all else, it’s a sense of community. “Exchanging ideas and feeling part of a community is about creating a platform of trust,” says the Chicago-born, Brooklyn-based artist.

In addition to being a painter, Westly works as an independent curator, art adviser and board member of the Black Artist Fund, a fundraising initiative that supports Black artists with grants, championing cultural equity and inclusivity and amplifying the voices of established and emerging Black artists of all ages.

“For many people, especially within America, the idea of pursuing an artistic vision can feel impossible,” Westly says. “Providing aid to African Americans shouldn’t just be restricted to those outliers deemed worthy of the title of ‘Black excellence’ or those living under the most extreme of circumstances, but should be offered to each and every artist with the courage, ambition and perseverance to make their dreams a reality.”

This February, 1stDibs has partnered with the Black Artist Fund to create our Black History Month collection of artworks from pre-eminent and emerging artists and photographers. In addition to our curatorial partnership and support of the Black Artist Fund throughout the month, several of the fund’s awardees have been offered subscription-free 1stDibs storefronts for one year.

Westly’s own art invites viewers to question so-called established truths about topics as diverse as ethnicity, politics and personal development. His large-scale oil paintings are often inspired by photographs of fleeting moments. Some are quiet and contemplative, depicting friends in domestic settings, while others are more socially charged and snatched from media sources, such as a freeze-frame taken during the January 6 U.S. Capitol riots last year (Axon Body 3, 2021.6.1) or a photo capturing the moment George Floyd was pulled from his vehicle by police officer Derek Chauvin (Axon Body 3 2020.5.25).

But these are not works of social realism. Perspectives are skewed, shapes are superimposed, and hyperreal elements are paired with abstract forms and blank spaces. Westly’s vibrant and fragmented aesthetic draws from the memetic nature of the Internet and social media. It is for us, the viewers, to peel back the layers of each story and place ourselves within his visions, which he describes as “translations.”

“Different colors and techniques in my art reflect the way our concerns are cut, shaped and tuned,” he explains.

According to Westly, the Black Artists Fund is a practical channel toward a more united and engaged front: “The BAF doesn’t restrict applicants and award recipients by age, sex, income or merit. We strongly encourage those who apply to do so by starting with a practical mindset.”

Artist-recipient Kayode Ojo appreciates this approach. “I was impressed by Darryl’s ability to generate funds without requiring me to validate or explain myself,” Ojo says, “which sets the BAF apart from other institutions.”

Grantees of the fund have been joining together to launch offshoot projects, like the FUBU group (named after the 1990s streetwear label For Us By Us), which includes male-identifying Black artists Ojo, Andrew Ross, Devin Kevin, Monsieur Zohore, Chase Hall, Marvin Toure, K.O. Nnamdie and Hugh Hayden.

Cofounded by Ojo and Westly, the FUBU collective takes part in weekly digital artist talks and lectures that Westly describes as “a symposium for investigating contemporary questions of identity, practice, art and community.”

It’s clear that the driving force behind Westly’s creative output is the belief that art has the ability to debunk dogmatic conceptions of culture, identity and status. “We are experiencing much of our lives through the Internet. But when we stop and consider the true implication of that moment, we may think differently,” he says

Here, we take a look at seven exceptional New York–area artists from a growing list of Black Artist Fund grantees who are using their own personal experiences and creative verve to craft visual poetry in genres as diverse as filmmaking, fashion photography, sculpture and public billboards.

KENDALL BESSENT

Just 22, Kendall Bessent has already made his mark on the art world as an innovative and evocative storyteller with intimate photographs that celebrate Black beauty and Black culture.

This year, the fine-art photographer and creative director was named one of Forbes 30 under 30 bright stars. “I remember the day that I found out — I was speechless. I knew that all the work that I’ve been doing and all the sacrifices that I had previously made were paying off,” says the Atlanta-born, Brooklyn-based Bessent, who has worked on commissioned projects for the likes of the New York Times, Netflix, Google, Elle and I-D magazine and who shot many of the portraits in this article, including his own.

Uncontrived yet beautifully cinematic, his portraits shine a light on the magic of ordinary moments. They speak of shared experiences as well as individual dreams and ambitions. ”I’m in the space now where I’m no longer interested in creating fantasy or fairy tales with my work,” he explains. “I’m focused on showcasing the authenticity and beauty of my community and culture.”

JOANNE PETIT-FRÈRE

Joanne Petit-Frère is best known for her intricate and arresting hair-braided sculptures. At once majestic, ornamental and mask-like, each of these textural and intricately handwoven works is a tapestry of thoughts and memories.

The Queens-based artist draws from a deep pool of influences, including her Haitian roots, architecture, the natural world and mathematics, as well as ideas surrounding beauty rituals in the African Diaspora, spiritual alignment, female empowerment and social mobility. She describes her art as “sequential and the braiding together of harmonious, disparate and even opposing elements.”

An alumnus of the Fashion Institute of Technology New York who also works with photography and film, Petit-Frère has had work exhibited at New York’s MoMA PS1; the California African American Museum, in Los Angeles; the Cooper Gallery, at Harvard University; and most recently, at Oklahoma’s Philbrook Museum of Art.

Her braided sculptures have appeared in the pages of Vogue, the New Yorker and AnOther Magazine and been worn by such notable figures as Beyoncé and Solange Knowles and Janelle Monáe.

ANDREW ROSS

“I like to think of sculpture as a site for an event, or as the aftermath of action,” says Andrew Ross, referring to his eclectic three-dimensional pieces combining casts of body parts, mass-produced objects and organic shapes crafted from media such as clay, wood and Styrofoam.

Far from familiar, these anatomical and architectural assemblages appear to be in a state of transmogrification, as if caught between fiction and reality. “I think of a lot of my figures as caricatures. As such, I acknowledge their limitations in representing groups or archetypes by showing them in a state of deconstruction,” Ross explains.

Born in 1989 in Miami and now based in Brooklyn, Ross has been widely exhibited both in the U.S. and across Europe. His fourth solo show recently took place at the New York gallery False Flag, founded in 2017 “to support artists willing to take a risk,” as the gallery puts it.

SYDNEY VERNON

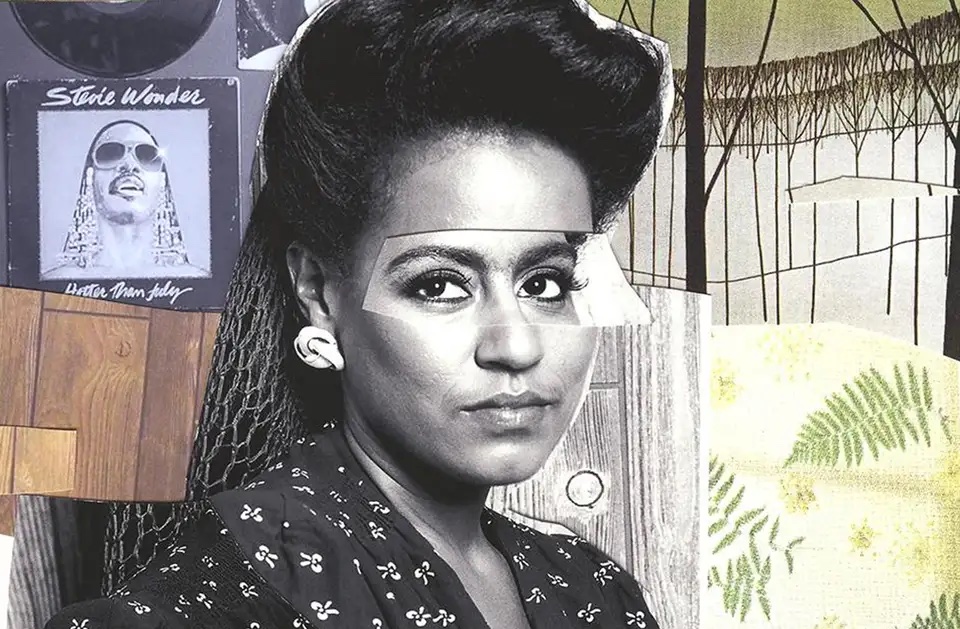

A recent graduate of The Cooper Union, in New York City, Sydney Vernon uses her own experiences and family memories to convey a prismatic perspective on Black culture, where history, ancestry, identity and community collide to challenge the Western portrait tradition.

Vernon often uses a combination of paint, pastels, collage and screen-printing to create her contemplative paintings, which infuse everyday moments with an air of gravitas and intrigue. Her talent for using autobiographical elements to unlock wider narratives has garnered much attention: Last year, she had her first solo show, at New York’s Thierry Goldberg Gallery, and she was announced as a winner of the #Your2020Portrait contest, a collaboration between the Brooklyn Museum and Instagram.

“In many ways, I find it difficult to express what it’s like to be a complex person with the capacity to grow and change,” she says. “So, with my work, I want people to understand how everything I do is connected to living as a Black woman, living in the Internet age, living in the wake of slavery and living in culture while simultaneously trying to create it.”

BRANDON NDIFE

Furniture and found objects take on new life in the hands of Jersey City–based artist Brandon Ndife. Tables, chairs, drawers are in a state of mutation, surrounded by earthy-looking excrescences handcrafted from painted resin and foam.

It’s hard to know if they are evolving or decomposing, but this very ambiguity is what matters, since it raises questions about home and displacement, rootedness and uprootedness.

Ndife, who was previously a painter, uses organic-looking forms to evoke a sense of vulnerability and chaos, literally “invading” the safe and familiar constructs of home to highlight how we are often at the mercy of forces beyond our control — a particularly poignant point now, in light of the pandemic. Drawing a parallel between the natural world and the current sociopolitical landscape, he uses this theme to spotlight the disruptive forces of racial inequality.

ASHLEY TEAMER

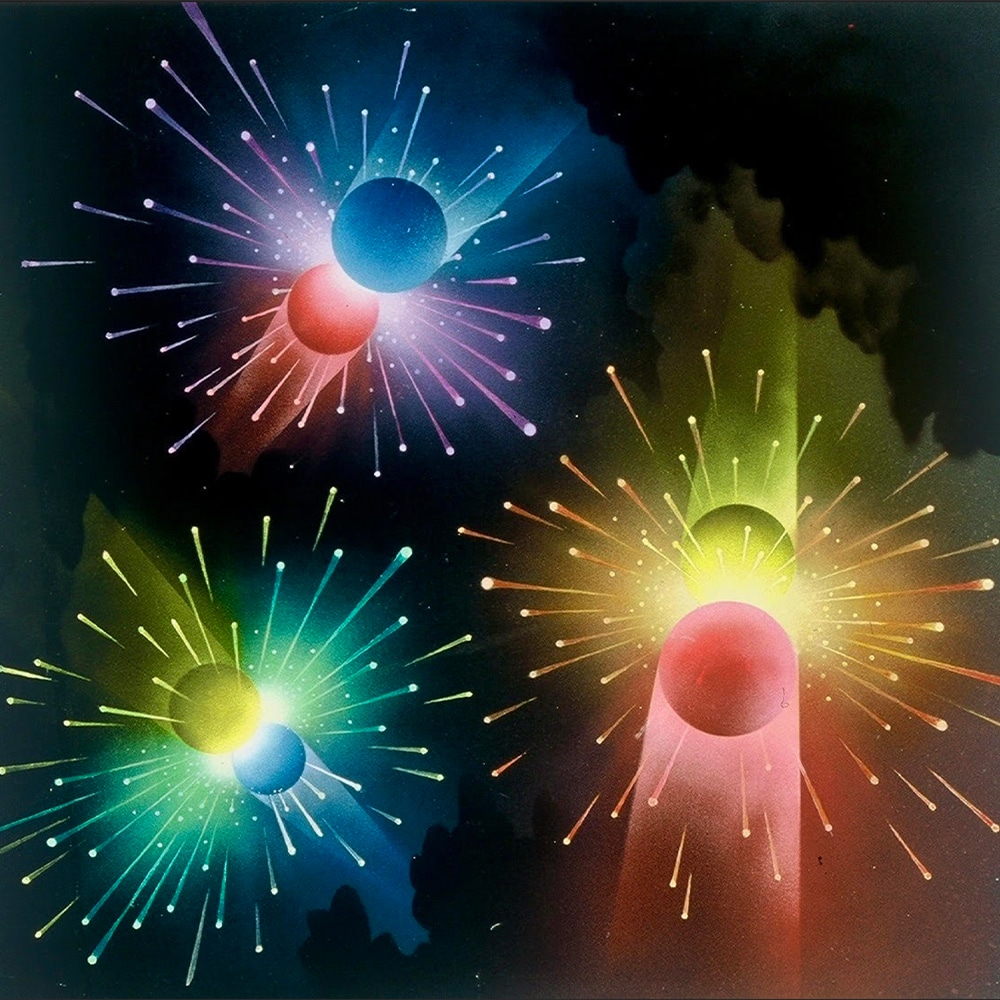

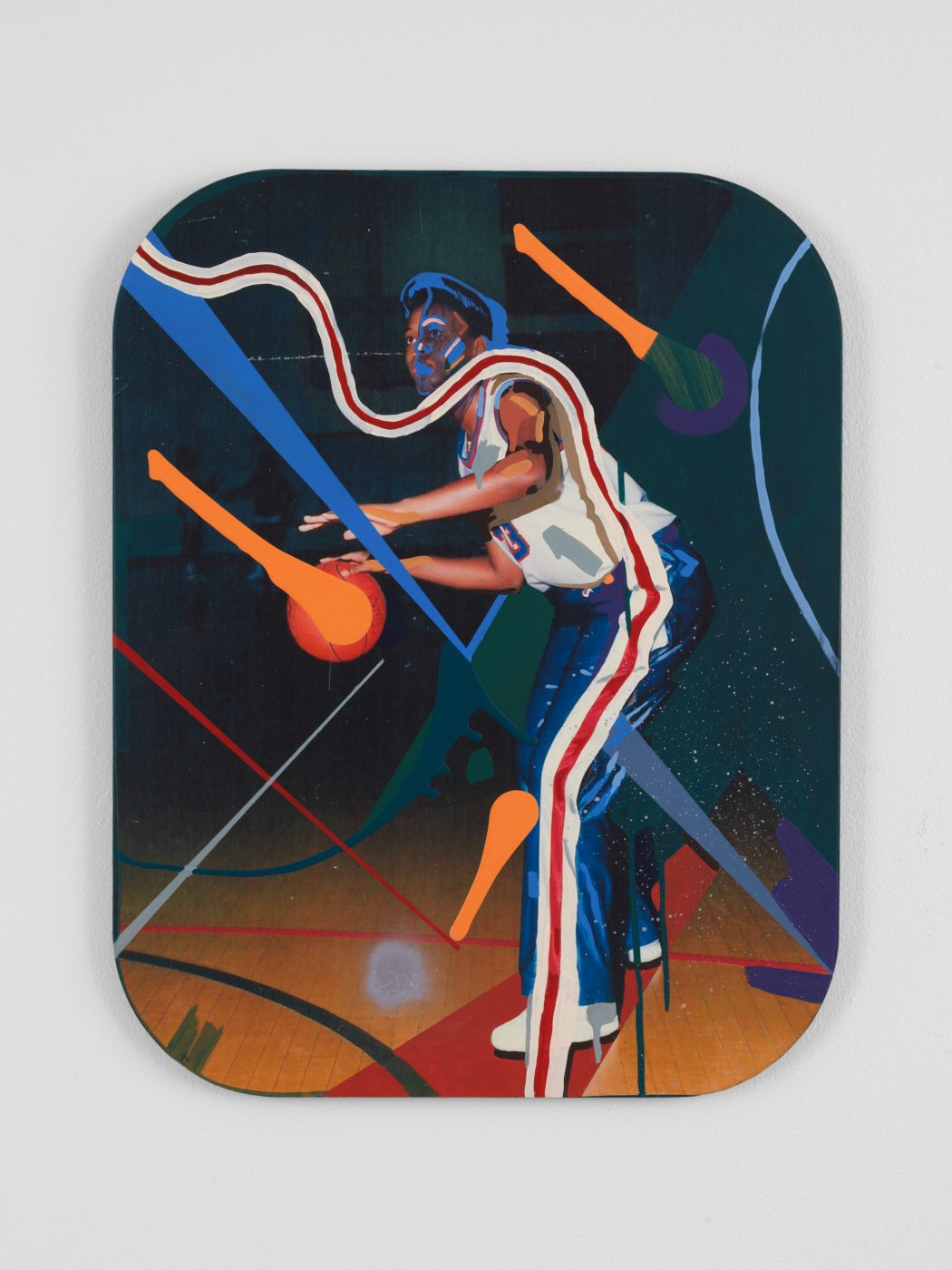

Ashley Teamer presents strong, sporty women in her dynamic collages, paintings and animations. The New Orleans artist, who’s currently an MFA candidate at the Yale School of Art, explores issues involving gender, power and Black femininity by ennobling women athletes in their element. Her specialty is the game-changing women basketball players who have helped to dismantle gender inequality.

“I got into basketball imagery from my love of sneakers. I made abstract paintings for years, using patterns that I saw on them,” Teamer says. “In 2014, my interest expanded to the people who imbued these sneakers with meaning: basketball players. I am always drawn to the players as they gaze upwards. The desperate reach of energy that is so full of momentum and potential power. I wanted to make work about this moment of possibility.”

The artist mines her own experiences and family history for inspiration: Her grandmother founded the Lady Bleu Devils women’s basketball team of Dillard University. Teamer recently created a series of eight billboards, displayed throughout New Orleans, that combine photographs by Annie Flanagan with archival shots borrowed from her grandmother’s archive from the 1970s and ’80s.

With this, her first public art venture, Teamer says, “I wanted to visually elevate these female players to the level of legend by depicting them as larger-than-life beings who stretch between earth and outer space.”

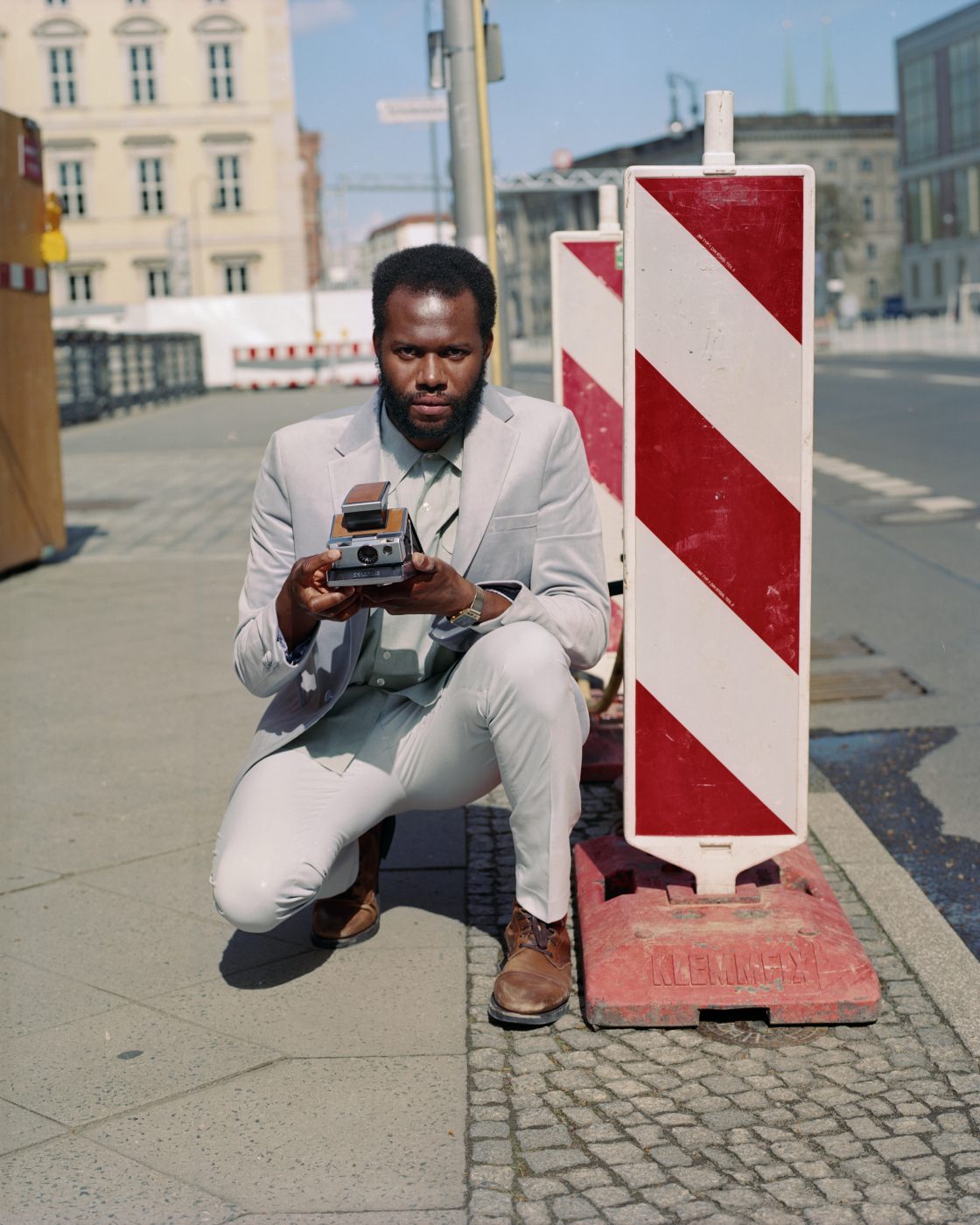

KAYODE OJO

The New York–based artist Kayode Ojo is an unconventional provocateur. His installations often incorporate music stands, glitzy fashion items, mirrors and body adornments like jewelery and wigs. The assembled sculptures have an almost anthropomorphic presence, as if they’re lingering guests from a hedonistic party that’s been and gone. But ambiguity looms large in his creative practice, which also includes portrait photography and clinical-looking readymades.

Artifice and theatrics are at work: Fashion items and gems are counterfeits, and the contrived glamour of his oeuvre is part of a parade that we all recognize and inevitably plug in to, raising questions about the complexities of self-image, ego and even, should you choose to go there, narcissism. It’s really up to you.

“My work doesn’t believe in authenticity. Much like myself, it does whatever it wants,” he explains. “It tries to look good but really doesn’t need you. It has its own internal logic. The work is only political if the viewer wants it to be. The only message I have is that sculpture and photography are connected.”