January 8, 2017A new book by author and critic Jed Perl is part one of the first-ever comprehensive biography of Alexander Calder, among the 20th-century’s greatest artists. Above: Calder poses in his Roxbury, Connecticut, studio in 1941 (photo by Herbert Matter, © 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York). Top: Vertical Foliage, 1941 (photo © 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York).

How is it possible that there hasn’t been a full-dress biography of Alexander Calder (1898–1976) until now? With his slowly spinning mobiles, the great American artist, a leading candidate for the top sculptor of the 20th century, completely remade our idea of movement in space.

Jed Perl’s new book, Calder: The Conquest of Time / The Early Years: 1898–1940 (Penguin Random House) is the deep dive we’ve been waiting for.

Even without it, Calder has remained highly relevant. Perhaps this is due to his strong presence on the art scene. There have been thoughtful shows like the recent “Calder: Hypermobility,” which closed in October at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, long a chief repository of his work, and then there’s the active programming of the Calder Foundation, run by his grandson Sandy Rower.

Perl — the author of several other books and a longtime art critic — tells a lucid, psychologically rich and well-detailed tale. He has plumbed the Calder Foundation archives for this very much authorized biography (of which the current volume is the first of two installments), and what he has come away with is a stabile-solid bildungsroman, with aspects of Oedipal drama and a Midnight in Paris bohemian flavor.

To say Calder was from an artistic family would be to understate the case: Both his father and grandfather were also sculptors, and he felt pressure to surpass them from a young age. Calder’s standard laugh line was, “I wasn’t brought up — I was framed,” since he was a model for his father, Alexander Stirling Calder, during his early Philadelphia youth. In the striking leaps of faith he took with modernism, he found a way to distinguish himself.

Calder created Croisière in 1931, the same year as his debut exhibition of abstract sculpture. Photo by Tom Powel Imaging © 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

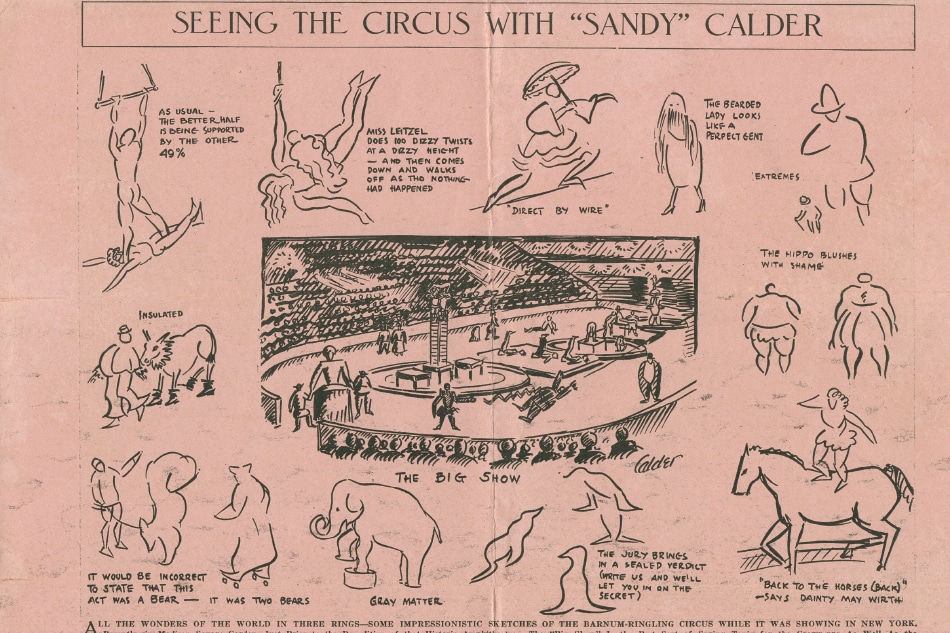

If you’re familiar with Calder’s work, it won’t surprise you to learn that from his earliest years, he loved the circus and spent much of his time drawing animals. This was part of what his parents termed the “play-instinct,” and they encouraged him to indulge in it as they moved around the country — to Pasadena, California, then Croton-on-Hudson, New York — basically letting him create or destroy at will.

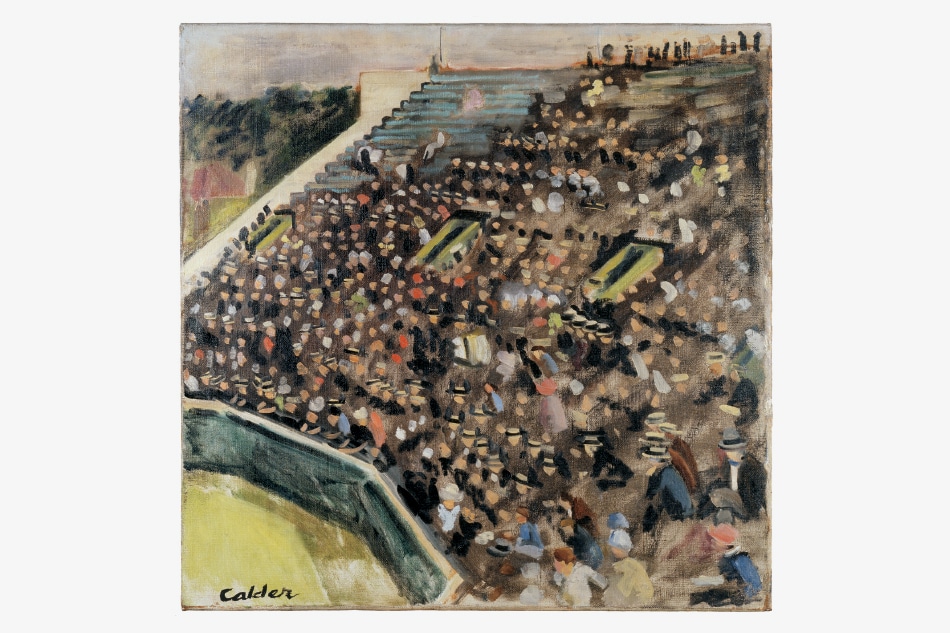

More unexpected, perhaps, is the time he spent studying engineering at the Stevens Institute of Technology, in New Jersey, although it makes sense, given his mastery of weight, balance and movement. And really eye-opening is the brief period — once he had moved to New York, following college — when he was painting canvases in the Ashcan School style of John Sloan and William Glackens.

A stint as a graphic illustrator rounded out his development. At one point, he occupied his father’s studio, as Andrew Wyeth had with that of his illustrator dad, N.C. Wyeth, in a similar act of generational baton passing.

For Calder, the fascinating moment of artistic alchemy comes sometime between his representational canvases of the late 1920s and 1931, the year of his first show of abstract sculpture. Perl notes that although it seemed as if Calder was “backing into” modernism — charming those around him, loosely experimenting and not truly paying attention to the developments in art — in truth, “he hadn’t missed a thing.”

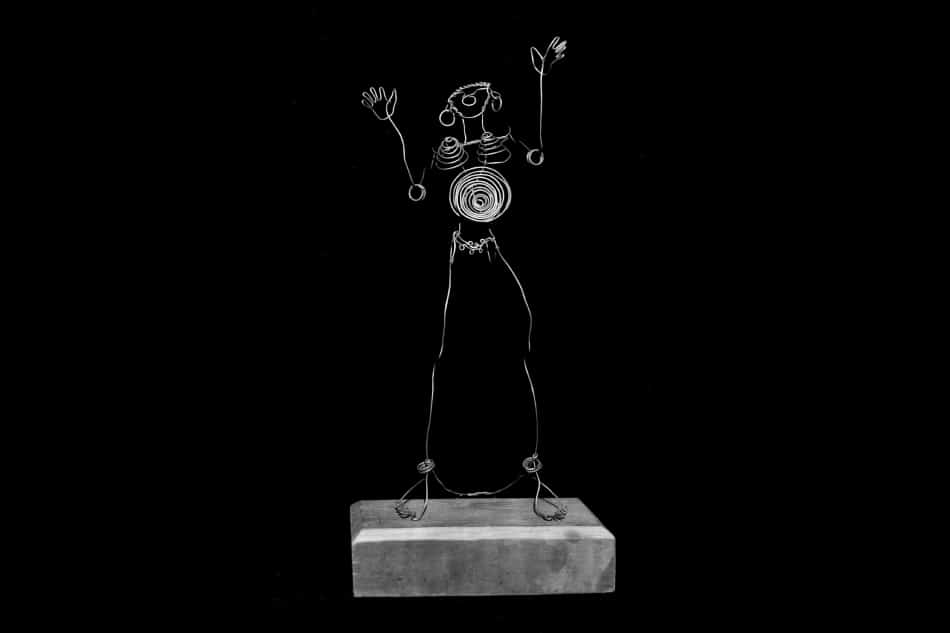

Moving to Paris helped spur his creativity, as it did for so many artists and writers who wanted to change the world, live freely and have affairs. The moment Calder arrived, he began working on one of his most seminal pieces, Cirque Calder (1931), his delightful distillation of the circus into what are essentially three-dimensional line drawings made with wire.

Calder began his jewelry practice after he moved back to American from Paris. He created this necklace (1937) and choker (1948) for his wife, Louisa James, whom he married in 1933. Photo © 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New YorkPhotography Credit: Maria Robledo

No less than Jean Cocteau — a true authority when it came to “sublime flimflam,” Perl writes — stopped by Calder’s workspace and wholly approved of the project. Lots of other famous names drift through the story, since this was a time when “everybody was being geniuses together,” in the words of author, poet and publisher Robert McAlmon, whom Perl quotes.

Cirque drew attention and became sought after, but Calder made an effort to leave it behind as he explored abstraction, absorbing the lessons of Constructivism and visiting Piet Mondrian in his studio.

Marcel Duchamp, truly on the leading edge at the time (and still in our own), suggested the term mobile for the kind of sculpture Calder was working on: biomorphic shapes that hung together but twirled individually, like a Joan Miró in motion. Calder loved the word’s double meaning in French, not only “movable” but “motive.”

Calder got married, to Louisa James, and moved back to the United States in 1933. They bought an 18th-century house in Roxbury, Connecticut, where he raised his family.

For his 40th birthday, he built himself a generous studio there, and his large stabiles (his term for standing sculptures) got bigger. He experimented with making distinctive jewelry, whose forms have exercised a persistent influence on the field.

Perl ends this installment in 1940, as Calder is becoming an established museum and gallery presence. The author deems this the point at which everything came together, when the artist’s “classical style” gelled. If you know the rest of the story, it’s a tantalizing moment to fade to black, with a Museum of Modern Art retrospective in the immediate offing and monumental public works being dreamed up.

Now, we just have to wait for Perl’s next and final installment, coming in the fall of 2019, to see what insights he brings to the second half of this fascinating tale.

Shop Alexander Calder on 1stdibs