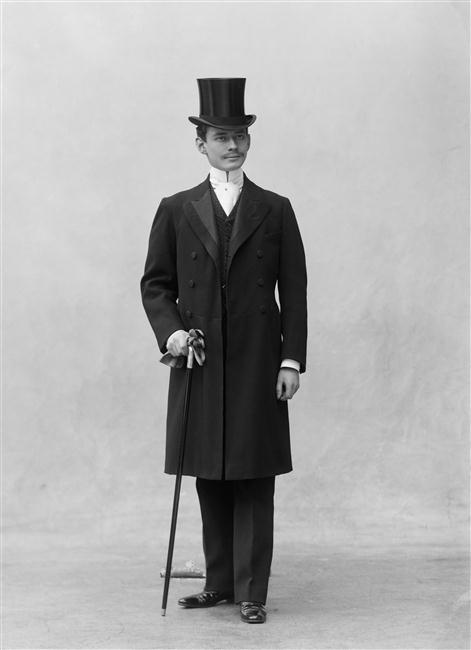

May 22, 2022Louis Cartier was an obsessive collector. A grandson of the eponymous house’s founder, Louis had interests in areas as diverse as Japanese inro and rare books. He regularly made excursions to the esteemed antiquities dealer Kalebdjian Frères, which was conveniently located across the street from the Cartier flagship at 13 rue de la Paix in Paris. Of all the treasures Louis Cartier collected, however, nothing captured his imagination as powerfully as Islamic art.

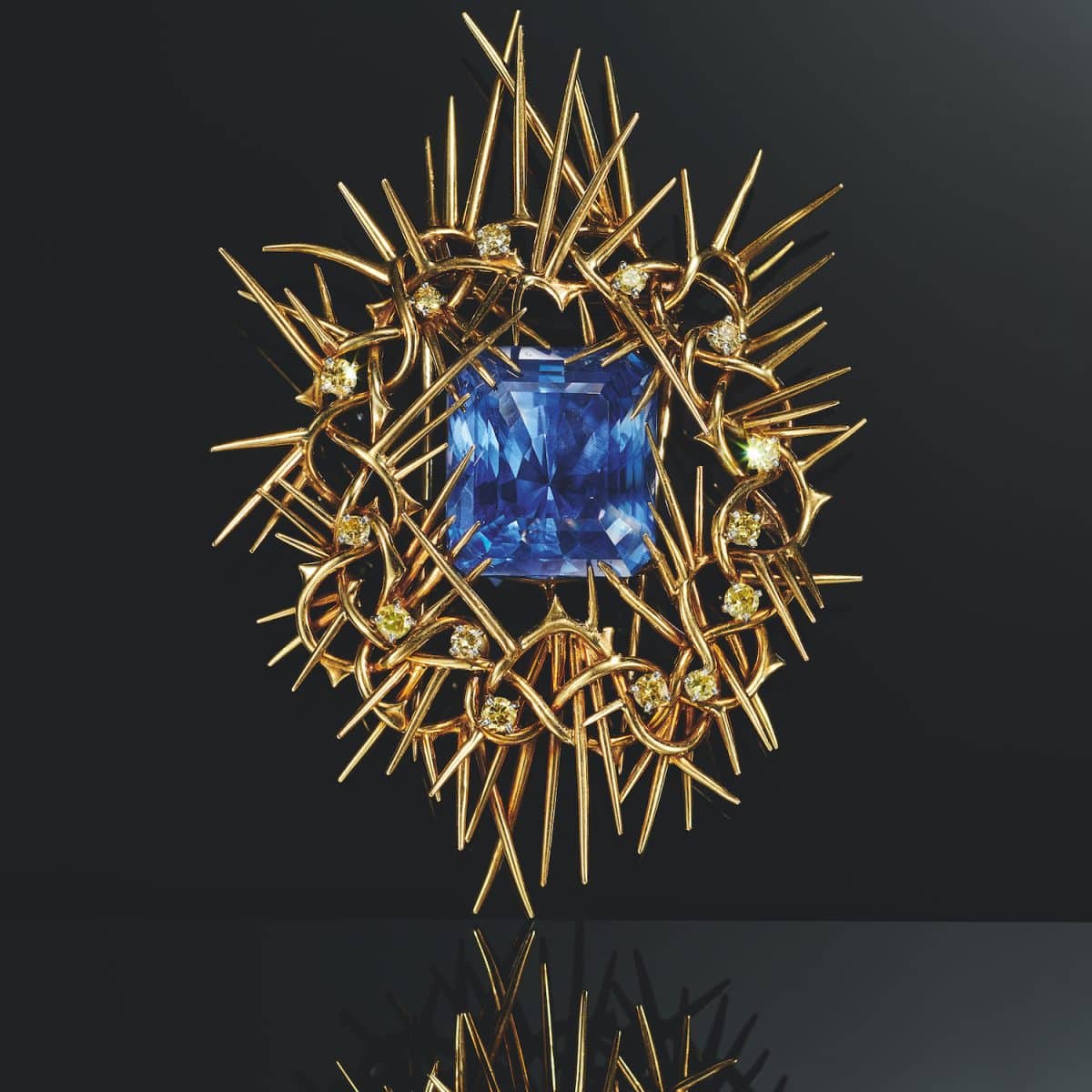

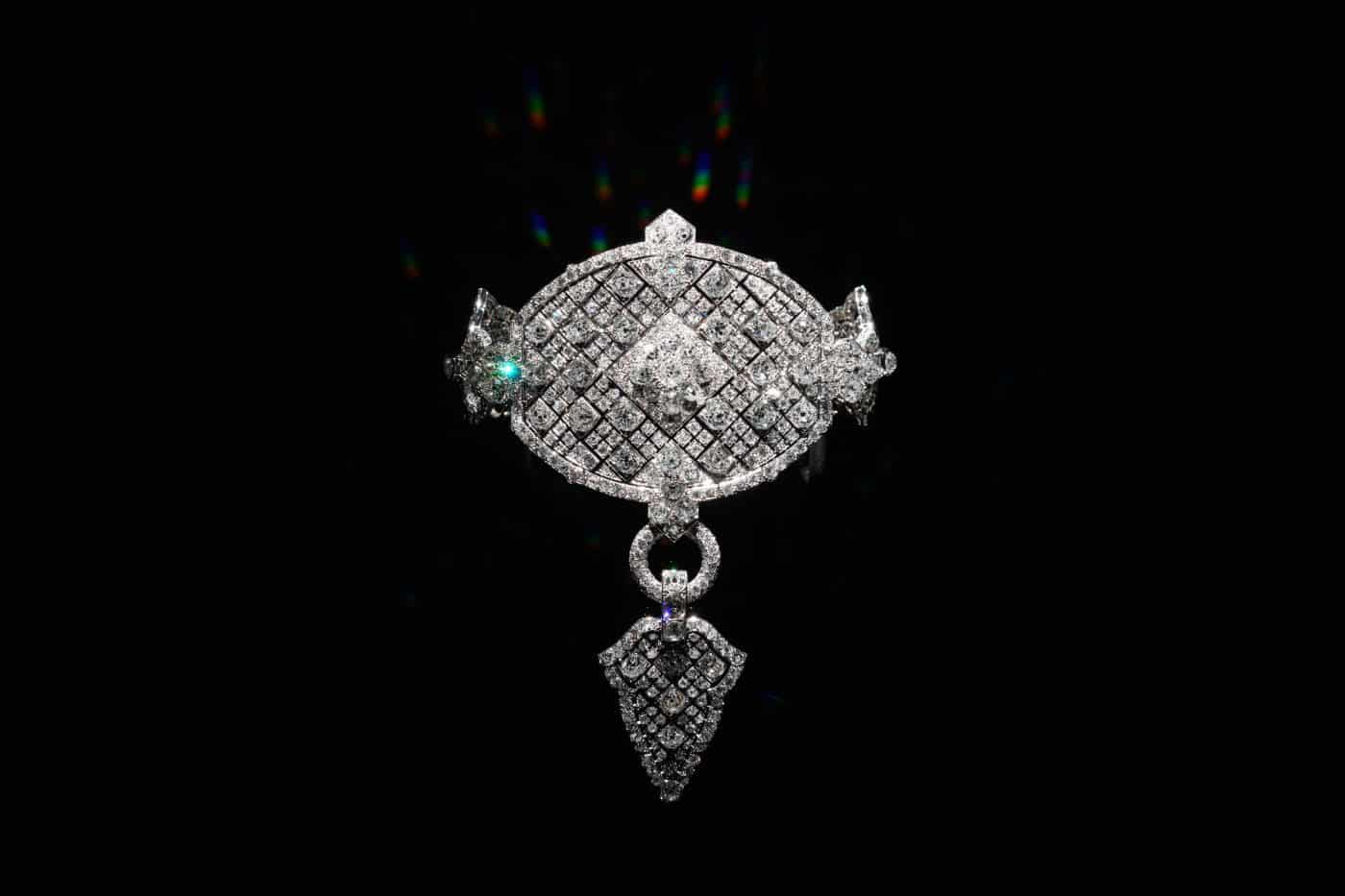

Cartier Paris gold and diamond necklace, ca. 2000. Top: This Cartier necklace features emeralds, rubies, sapphires and diamonds set in platinum, 2019. Exhibit photos by Daniel Salemi

When the jeweler died, in 1942 at age 67, his New York Times obituary reported that he had become almost as well known for his Islamic art collection as for his innovations in jewelry. During his lifetime, he loaned pieces to exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as well as the Musée du Louvre and other esteemed institutions throughout Europe. “The rise of Islamic arts as an academic field in the Western world was happening during this period,” explains Sarah Schleuning, the Dallas Museum of Art’s Margot B. Perot Senior Curator of Decorative Arts and Design. “I think it was a shift that was exciting and struck a lot of people with a creative desire.”

Louis Cartier did not just share his Islamic art collection with museums; he also provided Cartier designers, including the celebrated talent Charles Jacqueau, with Islamic art to keep in the design studio as a source of inspiration. Yet in the many Cartier books and exhibitions that have been published and staged over the years, the link to Islamic art has never truly been explored — until now, that is.

“Cartier & Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity” is currently being shown at the Dallas Museum of Art after debuting last winter at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. The landmark exhibition, which will remain in Texas through September 18, was organized by the two institutions in collaboration with the Louvre and with the support of Maison Cartier. The 400 objects presented include Cartier creations, Islamic works of art, books and decorative objects — all demonstrating how Louis Cartier’s enthusiasm for Islamic art influenced the house’s jewelry from the early years of the 20th century to today.

“The design strategies in this exhibition — motif, pattern and form — reveal the inspirations, innovations and aesthetic wonder present in the works of the Maison Cartier,” says Schleuning, who cocurated the exhibition. “Focused through the lens of Islamic art, it reveals how the maison migrates and manifests these styles over time, as well as how they are shaped by individual creativity.”

Cartier Paris made this ca. 1923 platinum and diamond bandeau tiara as a special order for Madame Ossa Ross. Photo by Vincent Wulveryck, Cartier Collection © Cartier

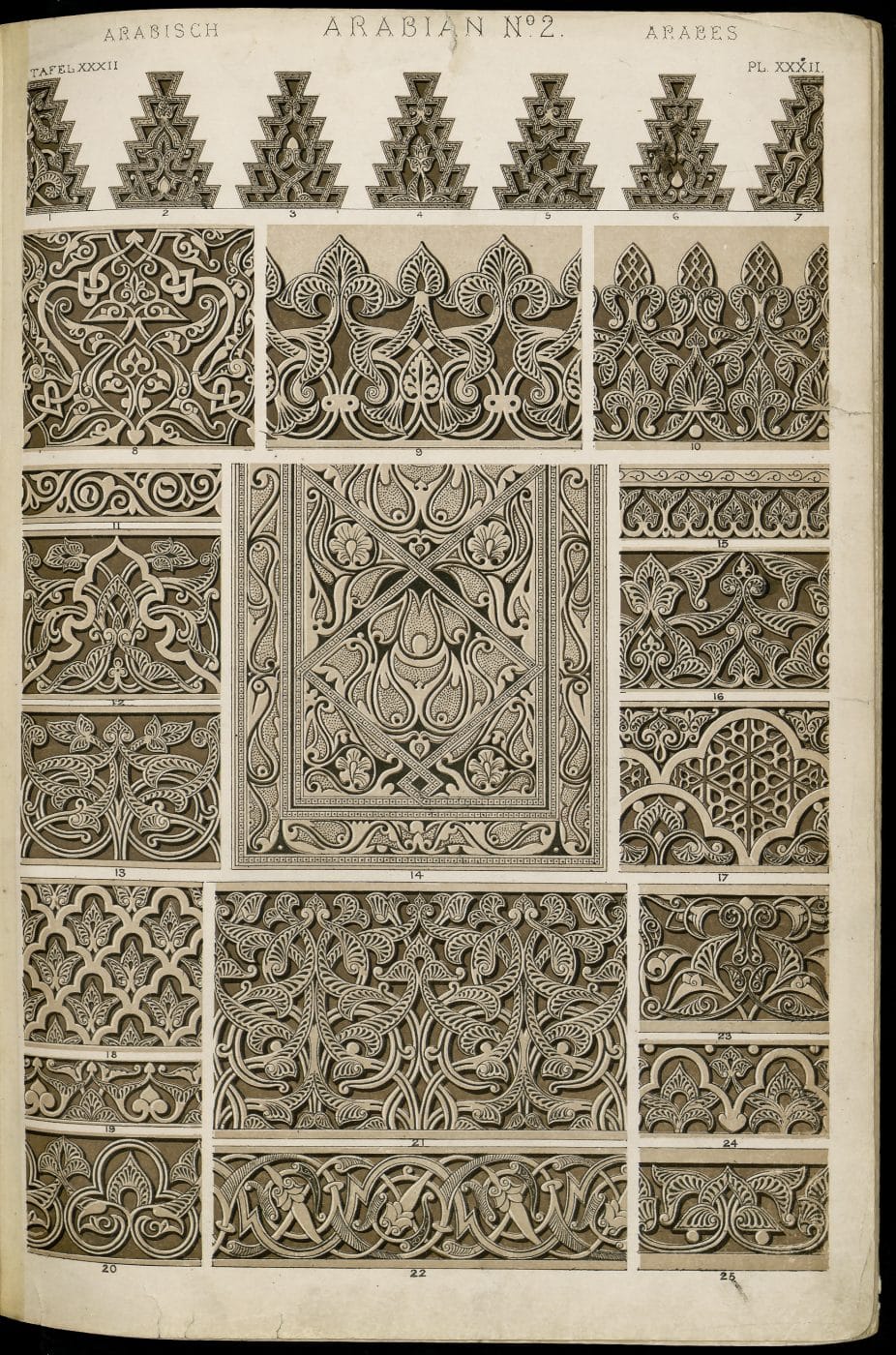

Displaying the Islamic art and Cartier creations side by side makes it easy to see the Cartier designers’ jumping-off points for jewels and objects. Studies in Cartier sketch books from around 1910 directly align with motifs in the “Arabian” section of Owen Jones’s 1856 publication The Grammar of Ornament. The lexicon of forms can also be found in platinum and diamond tiaras, bandeaux, bracelets and armbands created up until around 1923. While the white materials (platinum, diamonds) used for the jewels were absolutely in sync with the palette of the period, the geometric patterns were entirely different from the conventional royal motifs — bows, wreaths and flowers — employed in other jewelers’ designs.

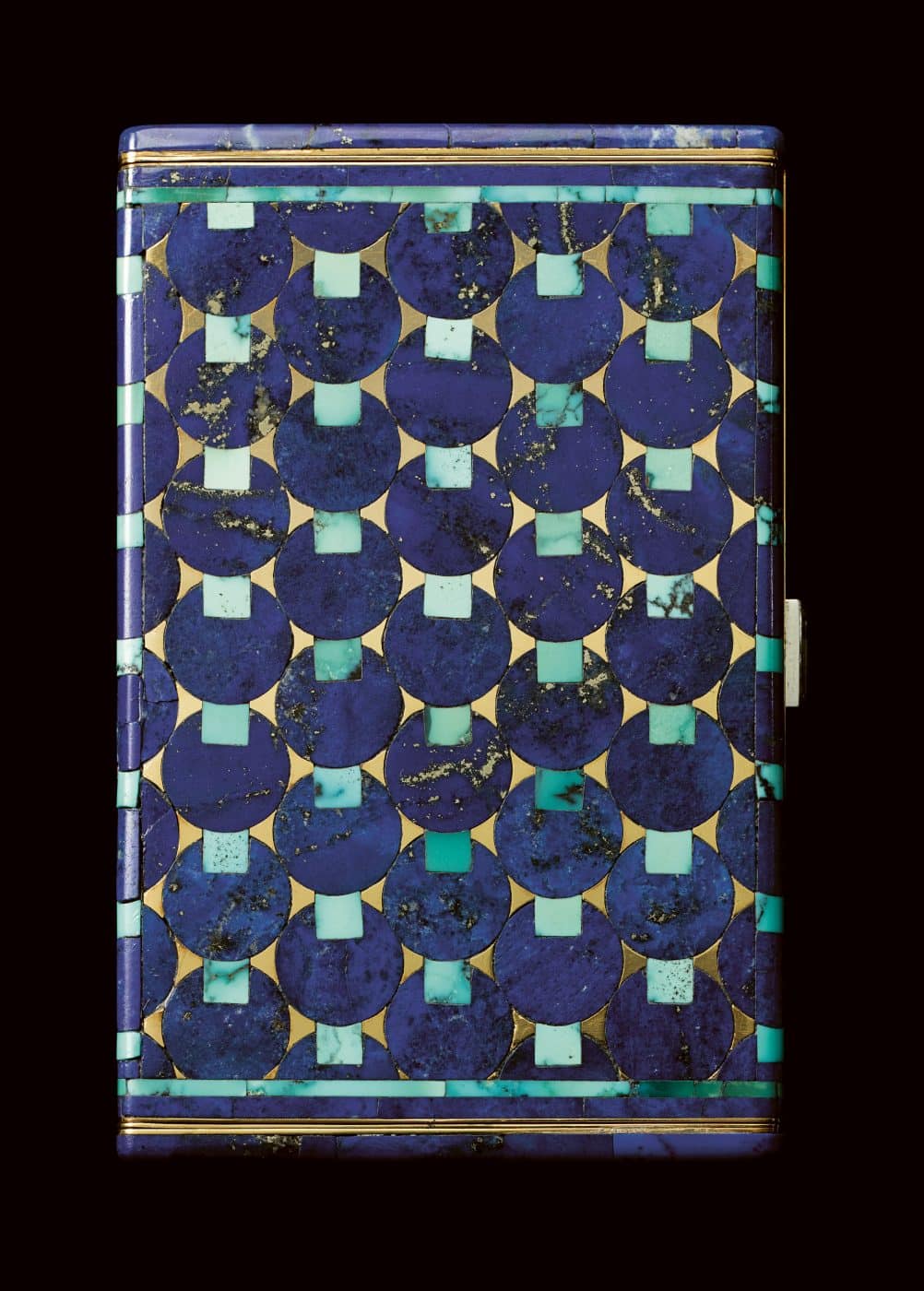

Cartier started incorporating the vibrant colors of Islamic art in the early 1920s, as fashion shifted from all-white schemes to a polychromatic mode. A cigarette case made in 1930 features a lapis-and-turquoise pattern reminiscent of Iranian ceramic tiles. Paisleys — also known as boteh and often used in Persian textiles — are imaginatively carved in the turquoise (most likely from Iran) decorating a Cartier diamond-and-platinum tiara made in 1936. A cartouche silhouette, similar in style to the ones seen in Persian carpets, forms the decorative pattern of a 1924 Cartier vanity case whose lid is composed of mother-of-pearl parquetry, turquoise, emeralds, pearls, diamonds and black and cream enamel. The pattern of amethyst, turquoise, diamonds and gold on a famous bib necklace made for the Duchess of Windsor in 1947 suddenly looks different in the context of the exhibition, evoking Iranian mosaic tiles.

“The exhibition provides an opportunity for visitors to see how Islamic art moved Louis Cartier, among others, and how ideas shift and change,” Schleuning says. “I do think that one of the roles that we have as institutions is to help connect those sources and where ideas came from. In the end, it is about creativity and inspiration.”