October 6, 2013Webb in his 57th Street showroom in 1975, not long before his death. Courtesy Women’s Wear Daily © Condé Nast

Asheville, North Carolina, was the sort of small Southern town where ambition meant a few years of high school followed by marriage and a local 9-to-5 job. For David Webb — born George David Webb on July 2, 1925, into a family of simple means with an absent father, an understanding mother and a couple of sisters — Asheville was a place best left behind.

Looking back briefly on those early years, Webb once recalled, “I had a tremendous feeling for art in me. I wanted to be an archaeologist, a ceramicist or a jeweler. Jewelry won out. My uncle owned a jewelry-manufacturing shop. I actually started working for him at fourteen, making dogwood flower pins.” At that point, he had already taken an art metalwork course, administered by the WPA, during which he made ashtrays signed with a little spider web, a clever riff on his name. Following a short stint in the army, Webb went to New York City when he was 17.

One likes to imagine that Webb arrived in New York’s Port Authority on a Greyhound bus, maybe one of the company’s fancy Silversides carriers. It was 1942, during the war years, and Greyhound was showing its patriotism by ferrying American troops across the country. Now, it brought to New York a tall, shy Southerner, a young man who had no money, no contacts, no job and no place to stay. But Webb had all the necessary intangibles: ambition, ideas and curiosity — ideal ingredients for a kid who was keen on self-invention.

New York was on the cusp of a new age of idealism and prosperity. Tiffany & Co. was a thriving American company with roots dating to the 19th century; single-owner shops such as Harry Winston, Paul Flato and Seaman Schepps had become important jewelers in the city; and the 47th Street Diamond District had claimed its Midtown location about five years earlier. This is the jewelry world that Webb discovered, and, within a matter of weeks, he was working in the Diamond District. By 1948, with the backing of French socialite Antoinette Quilleret, nicknamed Topsy, and Morton Rosenberg, Webb’s legal adviser, the jeweler opened his own shop, at 2 West 46th Street. (There were three employees and the jewelry was made on the premises, as it continues to be to this day.) Two years later, in 1950, his jewelry was featured on the cover of Vogue. He was just 25 years old.

Webb’s first magazine cover — for Vogue, no less — was in 1950, when the designer was only 25 years old. Horst/Vogue © Condé Nast

A lot had happened by 1950. Dior’s New Look had blown the lid off fashion and heralded luxury sans pareil and Abstract Expressionists such as Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning were upending the art world. American heiresses, including Doris Duke, Barbara Hutton and Gloria Vanderbilt, were making names for themselves on both sides of the pond, joined by new-money names like Annenberg, Paley and Lauder. On the West Coast, Grace Kelly, Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor were reshaping our notion of a Hollywood Silver Screen goddess. The following decade, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy tapped David Webb to make the official Gifts of State for the White House. All of these women, and their many friends and acquaintances, acquired fabulous jewelry. And all of them became clients of David Webb.

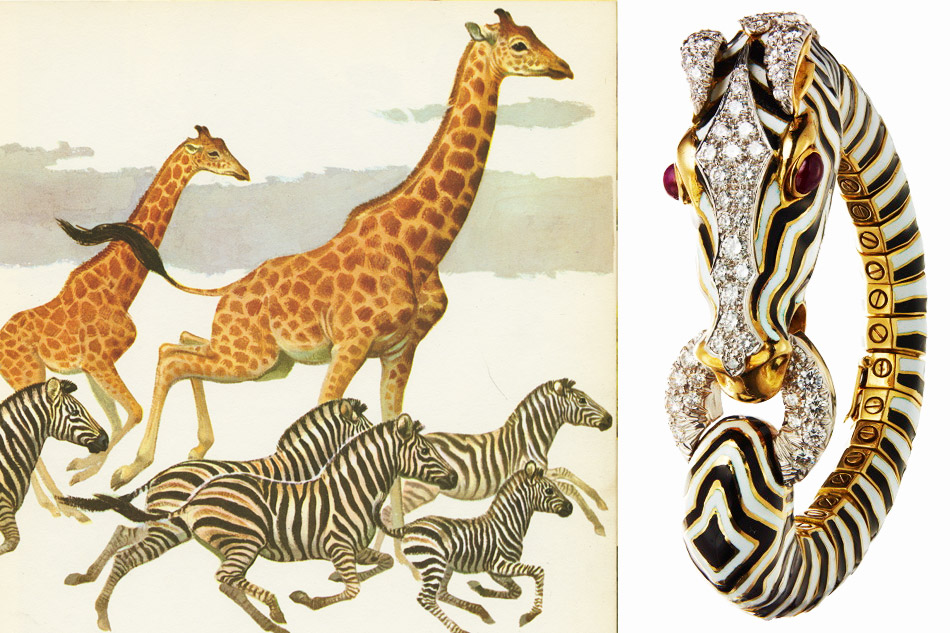

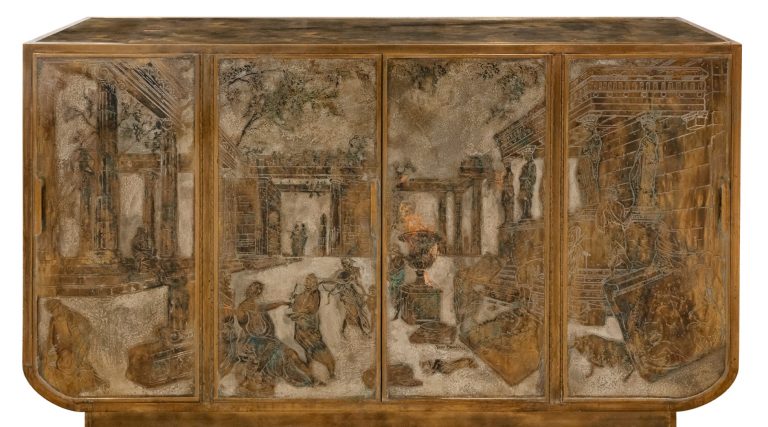

Webb was entirely self-taught. In his hometown, he was a near neighbor of Black Mountain College, with its progressive art curriculum. In New York, he was known for making weekly visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and he became a collector of Chinese art, Regency furniture and books about the fine and decorative arts of such faraway places as Peru, Africa, Spain, Indonesia and ancient Greece. He was a man of catholic tastes, whose library became the source material for his jewelry: an array of children’s books, including illustrated stories about jungle animals and how-to-draw volumes on horses and monkeys (used for his animal jewelry); the Life Nature Library (ideal for his bird and floral brooches); an encyclopedia of knots (a primer for his many gold-link necklaces); a rare book of engraved floral borders (re-envisaged as gold “frames” for the brooches he made from the assortment of antique jade he acquired); and a book on orders and ornaments (a major reference for his many Maltese cross brooches and pendants).

Above: The Elizabeth Taylor Double-Headed Lion Necklace, 1965. Right: The jewelry-loving actress wearing the Elizabeth Taylor Coral Maltese Cross Brooch in 1967 © Getty Images

Webb had a huge appetite for knowledge, coupled with an instinctive knack for rigorous editing. Webb chose, selected and refined what he learned, cultivating a design aesthetic that was ultimately and uniquely his own. His gold jewelry, for example, with its distinctive hammering and chasing, looks to the ancient past for inspiration. (“I had always been fascinated by barbaric jewelry, and very early jewelry,” he once said.)

His gold repoussé cuffs and fleur-de-lis pendants are both examples of ancient forms and traditional motifs finding their way into his au courant jewelry. Webb anticipated the trend for things Chinese and was prescient in his use of jade, which he began buying and turning into jewelry prior to Nixon’s trip to China in early 1972. He acknowledged being influenced by Chanel, though a much more significant and deeper impact on his work was Art Deco jewelry. Indeed, the three primary areas of influence in Webb are ancient Greek gold jewelry, pre-Columbian art and Art Deco. His use of rock crystal, which he scored, faceted, scalloped or left smooth, and often accented with diamonds, looks back to Art Deco jewelry, especially to works by René Boivin, Suzanne Belperron and Jean Fouquet.

Cartier’s pieces from the Art Deco period — whether a coral Chimera or rock crystal bracelet once owned by Gloria Swanson — also exerted their influence on Webb, as did scroll motifs (one of his signatures), which he picked up everywhere from Boivin’s Deco bracelets with scroll terminals to ancient C-scrolls. Even his concentrated use of enamel, which he made chic, was a nod to his Art Deco forebears. That said, however, Webb, ever mindful of his legacy, especially once he became ill with pancreatic cancer in his 50th year, said he believed that his “interpretations come off much better than the originals.”

An array of fabulous colored-stone rings.

Publicity settled favorably on Webb. The fashion press loved him, and he loved them. As the journalist Eugenia Sheppard once wrote, “Webb is the most fashion-conscious of the jewelers.” Photos taken by the likes of Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, Bert Stern, Horst P. Horst and Hiro attest to his fashion currency and show that when it came to the changing times ushered in by the 1960s and ’70s, David Webb was already ahead of the curve. His big, bold and colorful rings and his strongly geometric sautoirs were right in step with the designs of Pierre Cardin and Geoffrey Beene, Mainbocher and Courrèges.

Of all the materials he worked with, coral would probably be at the top of his list. In 1966 he remarked, “Coral has a whole new pizzazz about it. It’s timely, gay, young, it’s not precious.”

It’s this “not precious” look that speaks to the evergreen appeal of Webb and his American sensibility. He came of age as a jeweler working in a country that prides itself on its relative youth and its melting-pot culture. The boom years of post-World War II America were a welcome time for a young man with more ideas than money. As E. B. White wrote in his 1949 essay, “Here Is New York,” the city was a place for those “willing to be lucky.” It’s this combination of luck and daring, invention and openness to other cultures that resulted in the distinctive David Webb look: design, foremost, and a happy exuberance and energy, an anything-goes optimism.