Born in Italy, the longtime Manhattan-based designers Massimo and Lella Vignelli (above) created graphics, furniture, housewares, jewelry and more — and now, a new Rizzoli book shows off their oeuvre (portrait by Luca Vignelli). Top: A 1967 poster created for Knoll, now in the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (Elizabeth Torgeson-Lamark, RIT)

January 6, 2019Anyone who’s ridden the New York City subway has seen the work of Massimo and Lella Vignelli, the powerhouse Italian design team based in Manhattan from the 1960s until their deaths, in 2014 and 2016, respectively. The Vignellis shaped the aesthetic of the postwar 2oth and early 21st centuries in graphics, products and corporate branding familiar to us all.

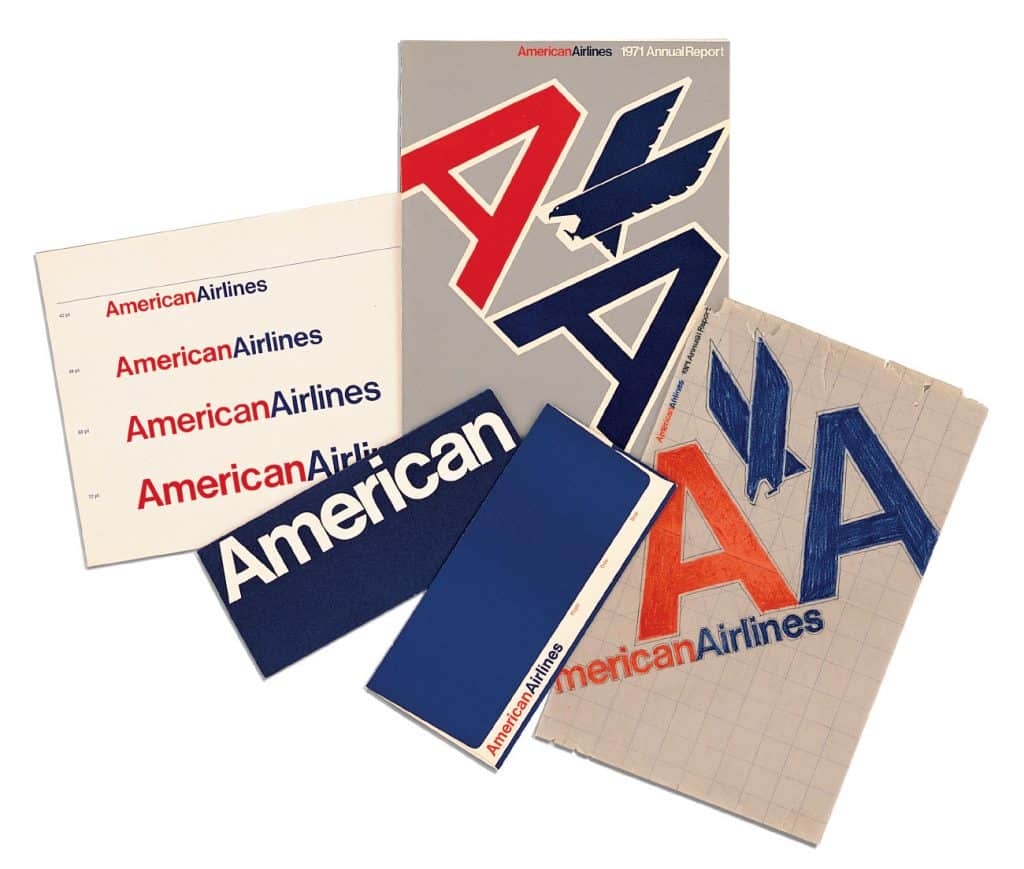

Bold clarity and pared-down elegance characterized the work that came flooding out of the 50-person Vignelli Associates office at 475 10th Avenue. The iconic oeuvre includes signage and maps for the New York and Washington, D.C., subway systems; the red-and-blue American Airlines logo, composed of an eagle and Helvetica lettering, that was emblazoned on everything from airplanes to napkins for 45 years; the rounded letters spelling “Bloomies” on the ubiquitous brown paper bags of Bloomingdale’s department stores; books and posters; cutlery and tableware; furniture and jewelry. Many of their designs are considered modern masterpieces and are included in the collection of New York’s MoMA and other important institutions.

After they designed a signage system for New York City’s Metropolitan Transit Authority in 1966, the MTA asked the Vignellis to create a new subway map. Photo by Reven T.C. Wurman

“It was the combination of their skills that made it work,” says Beatriz Cifuentes-Caballero, former vice president of design at Vignelli Associates and coauthor — with Massimo — of Design: Vignelli, a colossal new book from Rizzoli that’s sure to further cement the pair’s rock-solid reputation. “What they achieved was only possible with the two of them.”

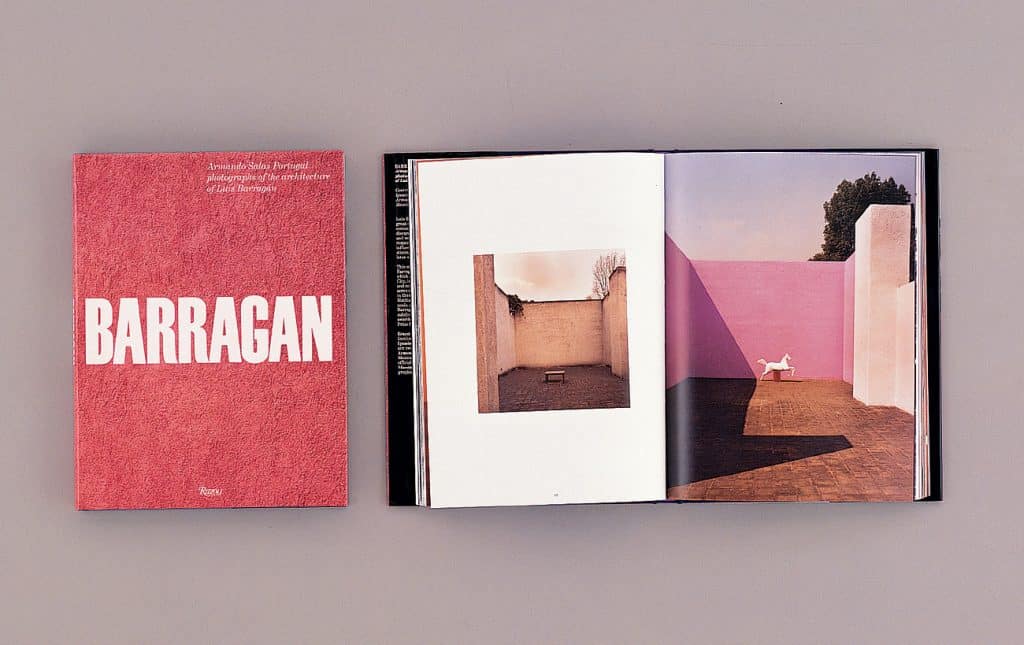

The cherry-red-covered, 408-page volume, which includes essays from a then-comprehensive 1990 monograph, plus several new ones and more than 800 images, is the definitive summation of the Vignellis’ lifework: from rarely seen early pieces to Massimo’s cheerful glass lighting produced by Venini in the 1950s to the architectonic silver neckpieces created in the early 21st century by Lella. By then, the firm had consolidated to comprise just the pair and a few associates, including Cifuentes-Caballero and Yoshiki Waterhouse, her partner in life and in the Queens-based Waterhouse Cifuentes Design, which could be considered the most direct heir to the Vignellis’ sensibility.

Introspective sat down with Cifuentes-Caballero to find out how the new book came to be and hear her intimate take on the Vignellis’ lives and influential work.

“As part of a series for the United States Bicentennial, this poster was commissioned to celebrate the ‘melting pot’ in American society,” according to the book, which Massimo coauthored with Beatriz Cifuentes-Caballero, former vice president of design at Vignelli Associates. Massimo “bought all of the foreign-language newspapers published in New York, and with them he made an American flag.”

The 1985 Serenissimo table, the authors write, “stresses the contrast between heavy, massive legs and very thin top.” Photo courtesy of Acerbis

This book was the work of many years. On his deathbed, Massimo made you promise to finish it. How does it feel to finally have it in your hands?

It is satisfying and a little sad at the same time, because it closes that phase of my life. The relationship I had with Massimo was close on a personal level. He was almost like my father. We started the book together, and it was difficult to go through the archives without him. I hope he’s happy with it.

How did you and Massimo come to develop such a close relationship?

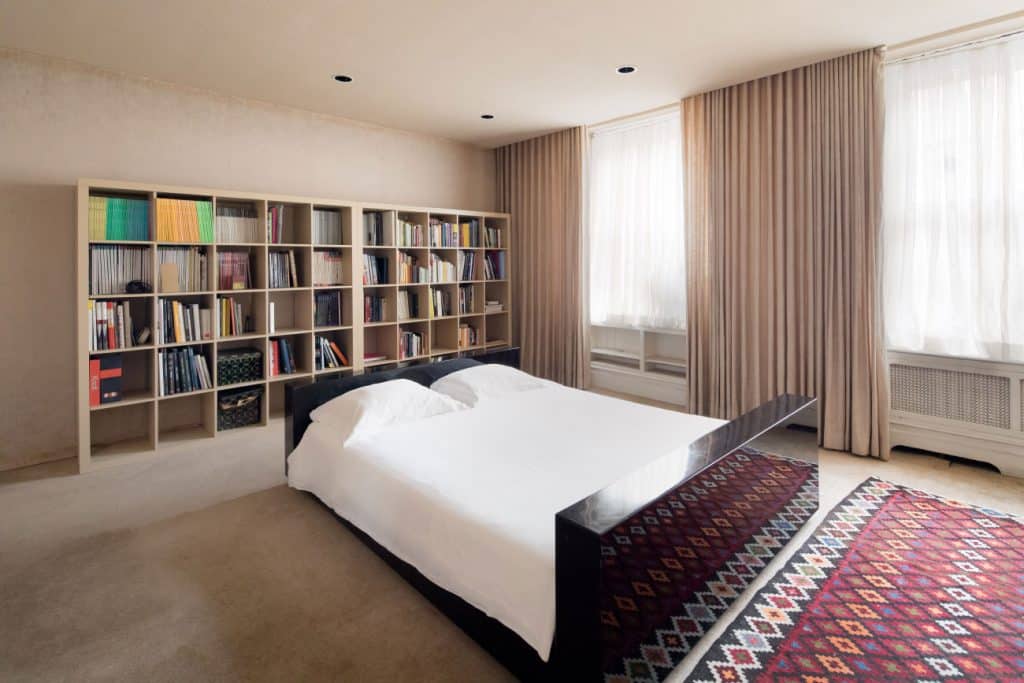

In 2000, the Vignellis closed their big office on Tenth Avenue and downsized from fifty people to just themselves and three others. I was one of those who went to work with them, along with my partner, Yoshi Waterhouse, whom I met at Vignelli. We worked out of their apartment on East Sixty-Seventh Street. With the office so small, the dynamics changed. We worked hand in hand with him every day. He and Lella became parents to both Yoshi and me, and when our daughter was born, Massimo became a grandfather figure as well.

I am Spanish, but I spent two years studying design at the Polytechnic in Milan, where Massimo also studied when he was young, and we spoke in Italian all the time. Life in the office was in Italian, and that was another factor.

People think the office stopped when we downsized, but that isn’t true. Massimo said we went from a big bus to a Ferrari. We had fewer but high-profile projects, and it was still a well-oiled team.

What led these two Italians to become committed New Yorkers after they arrived here in the nineteen sixties?

In Europe, everybody was doing multidisciplinary design, where if you can design one thing, you can design everything — “from a spoon to a city,” as Massimo said. Nobody was doing that in the States.

In the States, they were pioneers. They had a big influence here, more than in Europe. Massimo felt that Milan was still very provincial, but when they came to New York, they found big corporations who were willing to give them a chance to prove that through design, you could make a company greater than it was, even American Airlines.

In the early 1970s, the Vignellis created a collection of stacking tableware in a rainbow of colors for the Heller company that included these mugs.

From the Kenneth Frampton essay, which appeared in the earlier book, one gets the impression that Massimo was the artistic genius and Lella more of a helpmate. I’m glad to see you included an essay by Debbie Millman in the new volume as a corrective. Can you expand a bit on the contributions of each?

Lella Vignelli has always been underestimated. It was very important for me to give her recognition as an equal, even though it’s late. When they became these great iconic designers in New York, it was always a fight for her to be present and equal, and difficult for her to voice her authority in front of clients. She struggled to be heard and respected as a designer. Massimo tried really hard to bring her into the spotlight, but the social situation was not receptive.

I remember Massimo telling me that invitations would come only to his name. He would throw them away and not mention them to Lella. She was a very serious woman, and their design ideologies and philosophies were the same, almost one. But she was more in charge of the business. Massimo had zero business ambitions.

Their projects worked because of the combination of the two. They used to joke that they didn’t know if their marriage would have lasted if design was not involved.

“The Halo watch has seven rings of anodized aluminum in different colors of frosted plexi,” Massimo and Cifuentes-Caballero write. “The rings are interchangeable to combine with any outfit.” Photo by Elizabeth Torgeson-Lamark (RIT)

Massimo had a very high-minded approach to design. He vowed to “oppose all visual pollution.” His use of typefaces was limited to just five fonts. He was even bothered by the standard American eight-and-a-half-by-eleven paper size! He called its proportions “ugly.” Wasn’t it hard for a person of such sensitivity to live in this world?

For them, design wasn’t just isolated objects. They saw everything as part of systems. The American imperial system for paper sizes is not transferable by doubles or halves. The system was ugly to him because it was chaotic and random. All their products draw on the cube, cylinder and sphere.

Instead of letting ugliness bother them, they saw themselves as destined to change it. Massimo wrote a lot in his last years about his design philosophy. He truly believed you could make the world better through design.

That’s something they always said: If you can’t find it, design it. Massimo got up one morning in the eighties and went to his closet, and everything looked outdated, and he was tired of fashion. So they designed a line of clothing.

Of all their contributions to product design — furniture, tableware, jewelry — what is your personal favorite?

If I had to choose one thing personally, I would say that the most beautiful objects are the jewelry Lella made. Those are stunning pieces, jaw-dropping. Every time she went somewhere, she was the center of attention. I have the snake-like Senzafine (Infinity) necklace, and when I go to a party with it, people don’t see me, they just see the necklace.

Shop Massimo and Lella Vignelli on 1stdibs

Purchase This Book

Or Support Your Local Bookstore