July 13, 2025“Diane Arbus: Constellation” may be an unlikely summer blockbuster, but it makes a deep impression. Installed in the grand drill hall of New York City’s Park Avenue Armory, the exhibition is vast and dense, comprising a whopping 454 pictures taken by Arbus (1923–71), photography’s great poet of outsiders and eccentrics.

The black-and-white images are attached to a series of open metal armatures — the installation evokes a network of picture frames — meaning that you can always see beyond the photograph in front of you and catch glimpses of other portraits, making it feel like a true gathering of the people Arbus captured in her off-center way.

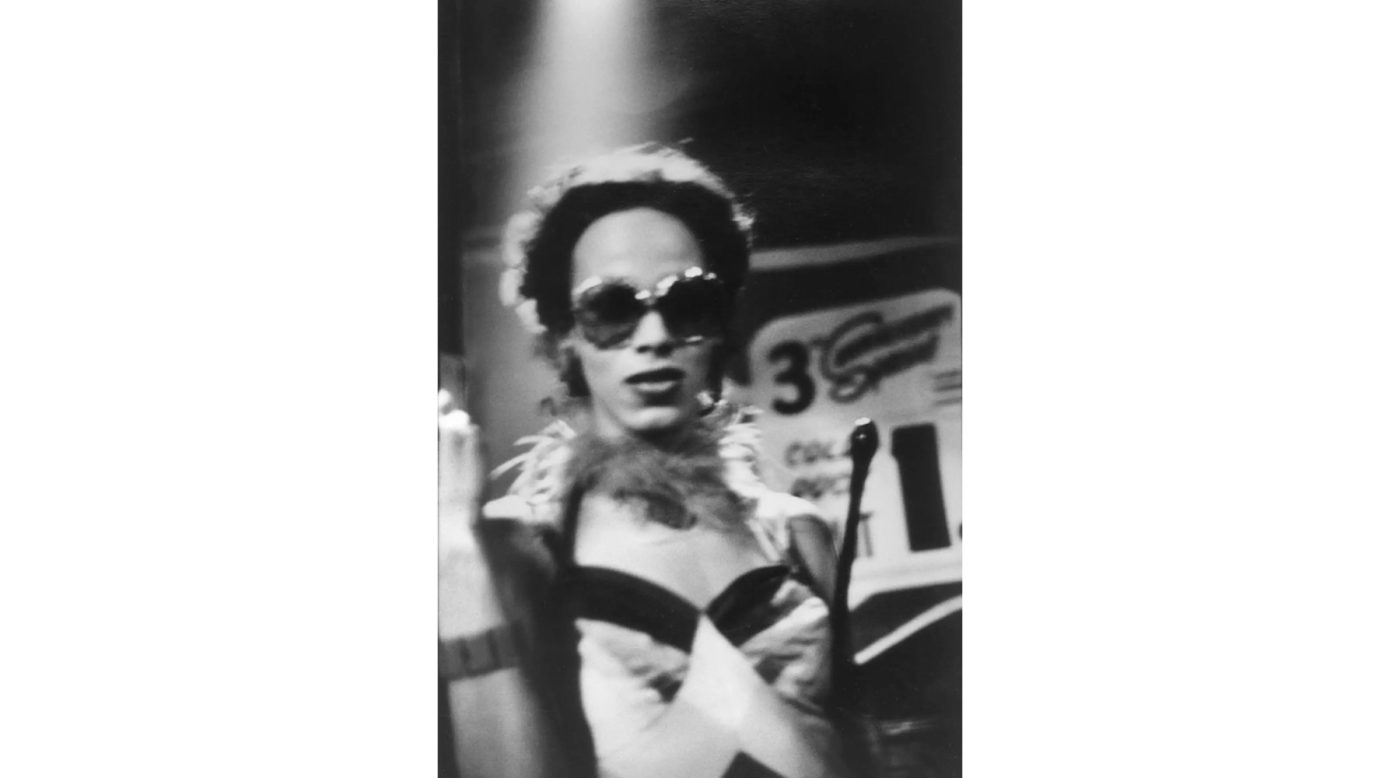

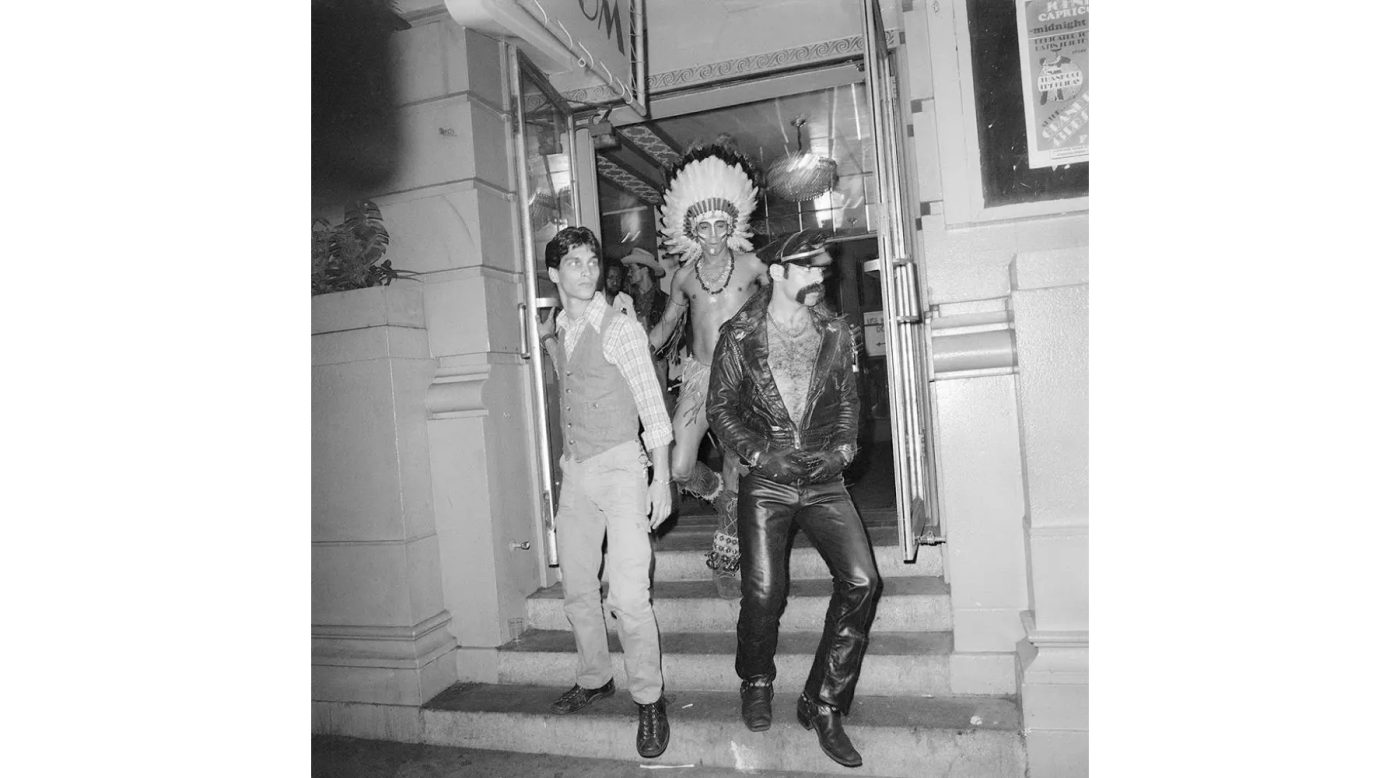

If you have a favorite Arbus image, or one that’s just burned into your brain, it’s here: the strange boy holding toy grenades, the placid nudists, the “Jewish giant” with his parents, the circus performers and drag queens, the twins and triplets.

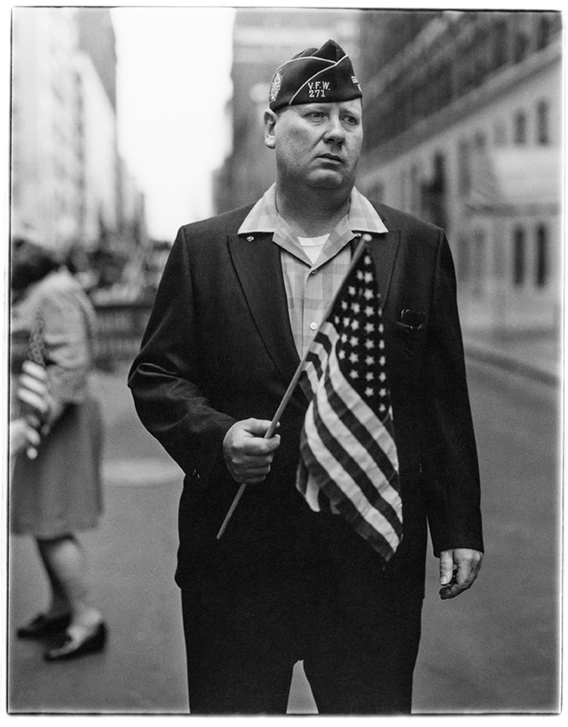

The intense connection between photographer and subject is still shocking on some level — there’s an electric current of empathy, even though at times critics have wondered if she was exploiting some of them. The contemplative look on the face of the man in Veteran with a flag, N.Y.C. 1971 is Arbus catching someone in the act of being truly himself.

The 1960s hairdos and interiors may ground her shots in “a certain moment in history,” says the New York art dealer Brian Paul Clamp, who sells Arbus’s photographs, “but they still have this universal quality that fascinates.” Indeed, the once-radical work even starts to take on a classical air the farther away we get from it.

On view until August 17, “Constellation” was curated by Matthieu Humery for the Zurich-based Luma Foundation and is presented by Luma and its patron, Maja Hoffman, as sanctioned by the Arbus estate. It first appeared at Luma’s exhibition space, in Arles, France.

“I wanted this labyrinthic aspect — you move around, and you don’t know where you’re going to walk,” Humery says of the complex installation. “It gives you a lot of energy.” When he presented the idea to the Arbus estate, he says, “they were surprised but said, ‘Let’s try it.’ ”

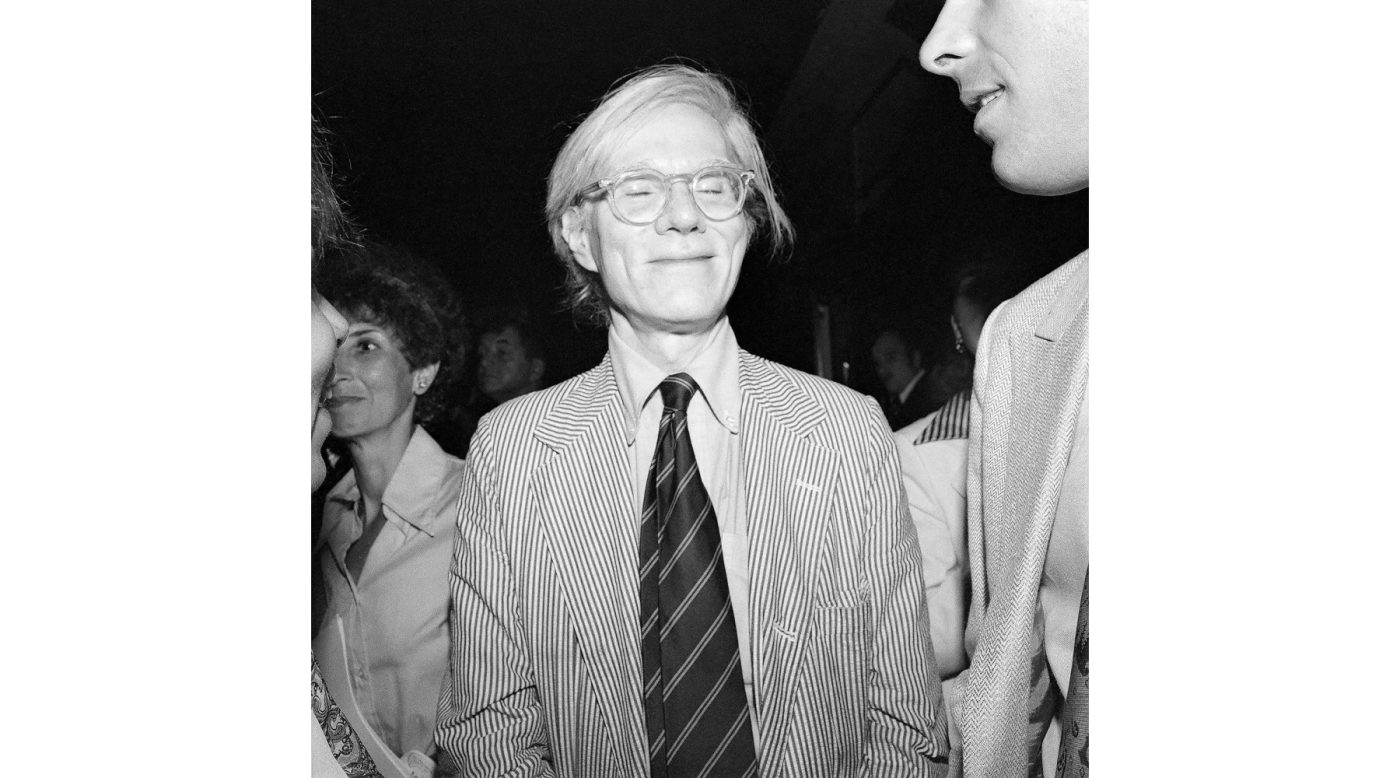

Arbus’s portraits of big cultural figures — Frank Stella, Susan Sontag, Joan Crawford, Agnes Martin, Anderson Cooper (as a baby) — may actually be some of the least-familiar images, and everyone will see something new. “With this show, at this size, what’s nice is that there are images that are much less known,” says Humery. “You have to go through it to discover them.”

A vital force behind “Constellation” is Neil Selkirk, who printed all the images and is the only person authorized by the estate to do so.

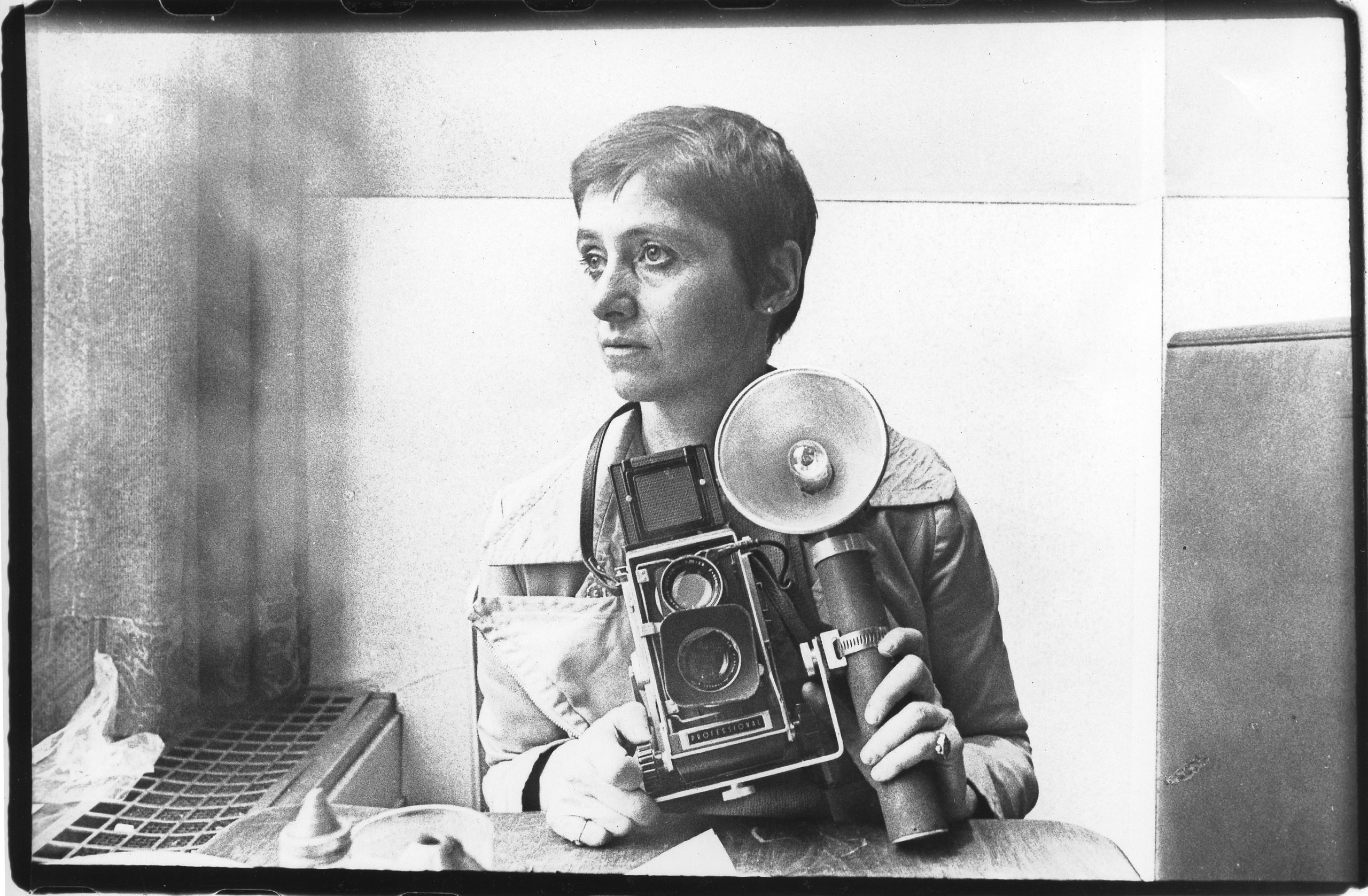

The British-born Selkirk, who is a talented photographer in his own right, got to know Arbus in 1970, when he was in his early 20s and working as an assistant in New York for the Surrealist-inflected fashion photographer known as Hiro (1930–2021, born Yasuhiro Wakabayashi).

“He had collected this Arbus photo, and I had no idea who she was,” Selkirk recalls. “It blew my mind.” He met Arbus when she stopped by Hiro’s studio.

At the time, Arbus, then known for the square images made by her twin-lens Rolleiflex camera, was considering experimenting with photography formats.

The native New Yorker had begun her career doing fashion and advertising photography with her husband, Allan, achieving much success at publications like Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar before striking out in the late 1950s on her personal artistic journey. She had never had too keen an interest in the technical side of the medium, says Selkirk, but she was curious about Hiro’s use of a Pentax camera. Selkirk, despite his youth, became a technical adviser of sorts. “My first interaction with her was showing her how to use it,” he says. “Then, she would call me from time to time.”

She didn’t really take Selkirk’s advice, however. “She winged it,” he says. “She did what she did, and the results were magical. She never would have gotten that if she had listened to me.”

Arbus took her own life in 1971. But their association led to Selkirk’s becoming, after her death, the printer of the photographs in the legendary 1972 Museum of Modern Art retrospective of her work.

“I was given three hundred and five little thumbnails and seven thousand rolls of film and contact sheets, and it took me the better part of a year,” says Selkirk. “In the process of learning how to duplicate them, I learned that she did not manipulate them at all. My success is based entirely on being able to replicate that look.”

As one of the only people around who actually worked with Arbus, Selkirk has special insight into why her pictures are so highly valued — at Christie’s last year, one of her most famous images, Identical twins, Roselle, N. J. (also in “Constellation”), went for nearly $1.2 million.

“Diane wanted to know what it meant to be human,” Selkirk says. “She wanted to know what motivated everyone.” And she lacked some common inhibitions. “She had a complete confidence in herself. She had no interest in judging [her behavior] against social convention.”

From a collecting perspective, Clamp says that the typical buyer of an Arbus image is not necessarily a photography specialist. “She’s a good example of an artist who breaks through barriers of a medium,” he explains. “She’s such a big name, and everyone has some familiarity with her work.”

If a collector can’t snare an Arbus, there is the work of the many photographers whom she influenced. Rare is the maker of a black-and-white image or a portrait in the post-Arbus era who doesn’t name her as at least a reference point.

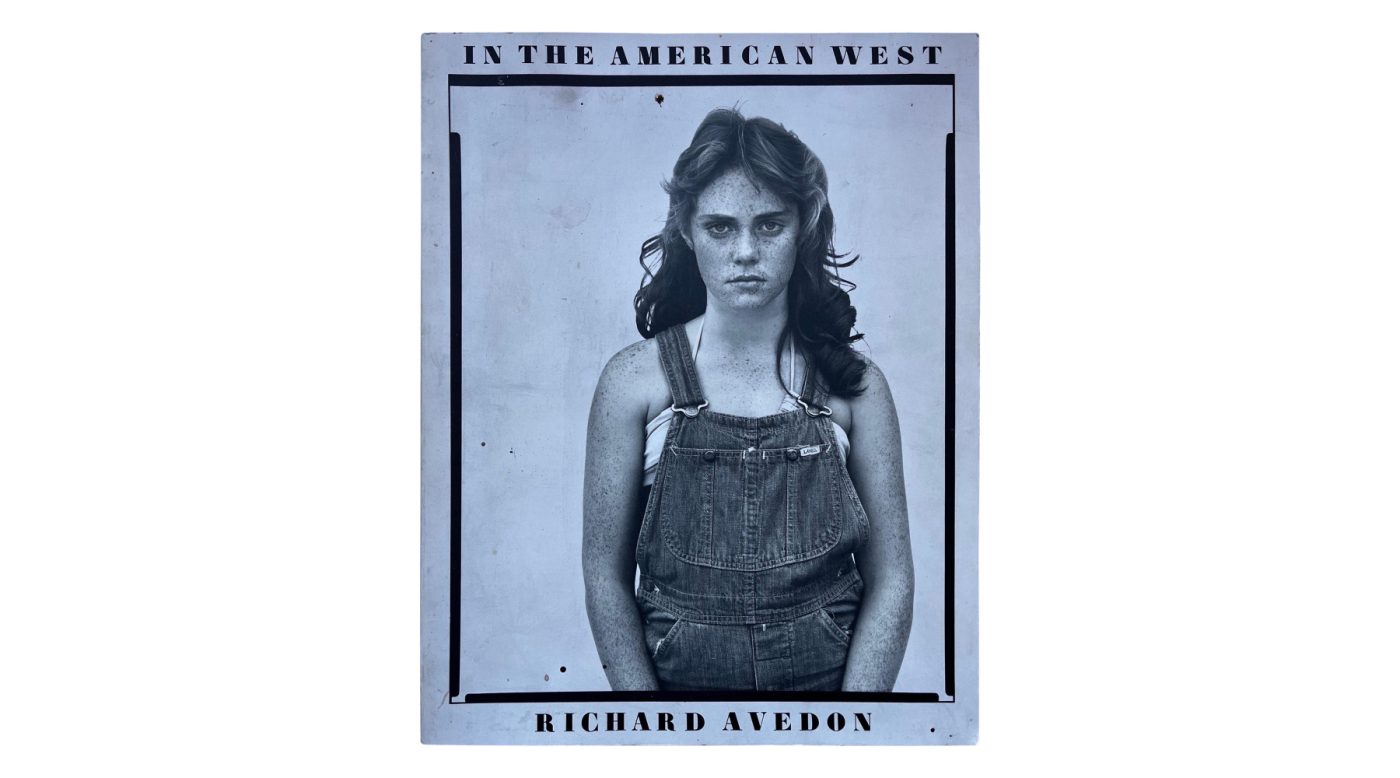

Humery notes that her influence even extended to her friend Richard Avedon. Although best known for fashion work, Avedon created a very diverse oeuvre, which included many portraits. Humery says that his early-1980s “In the American West” series — depicting the regular folks and quirky culture he found on his travels — shows him trying to approach what Humery calls the “freedom” Arbus gave herself to follow her instincts.

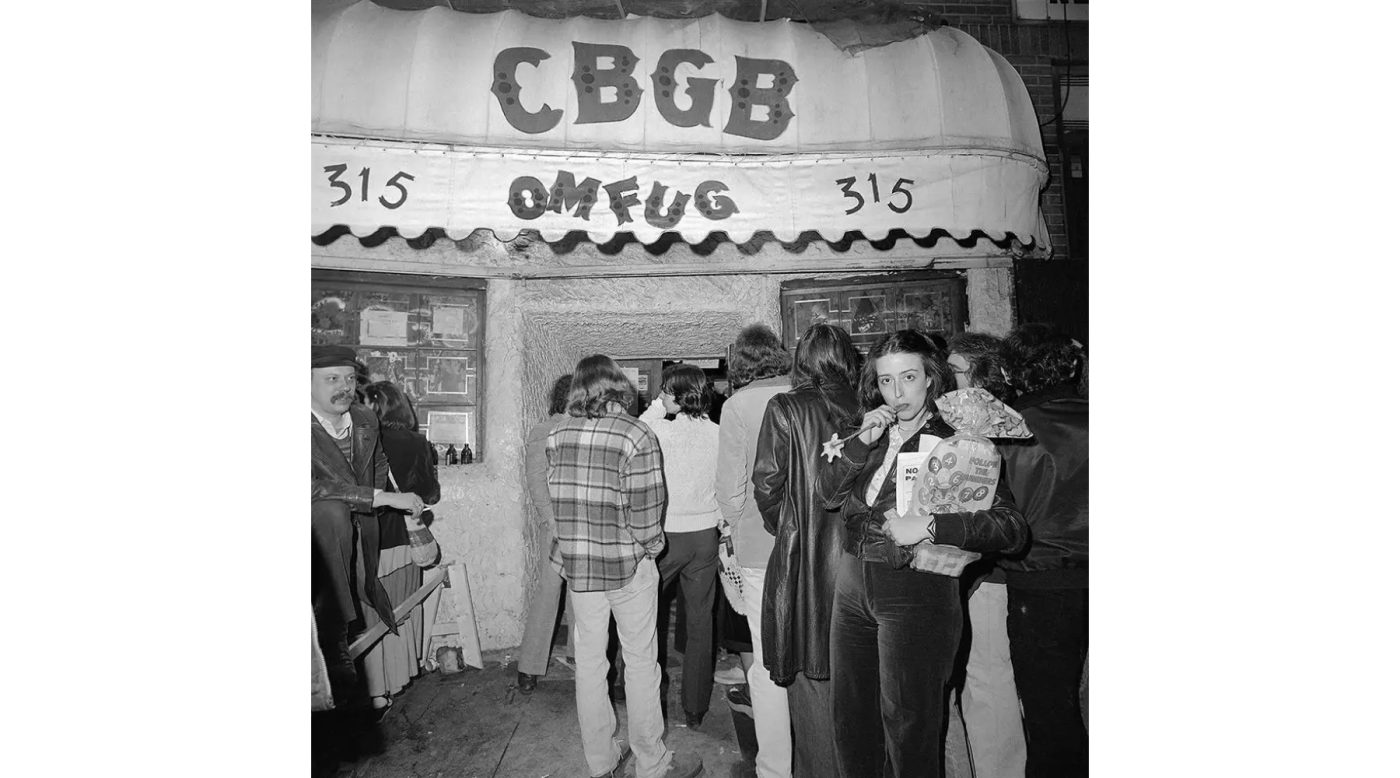

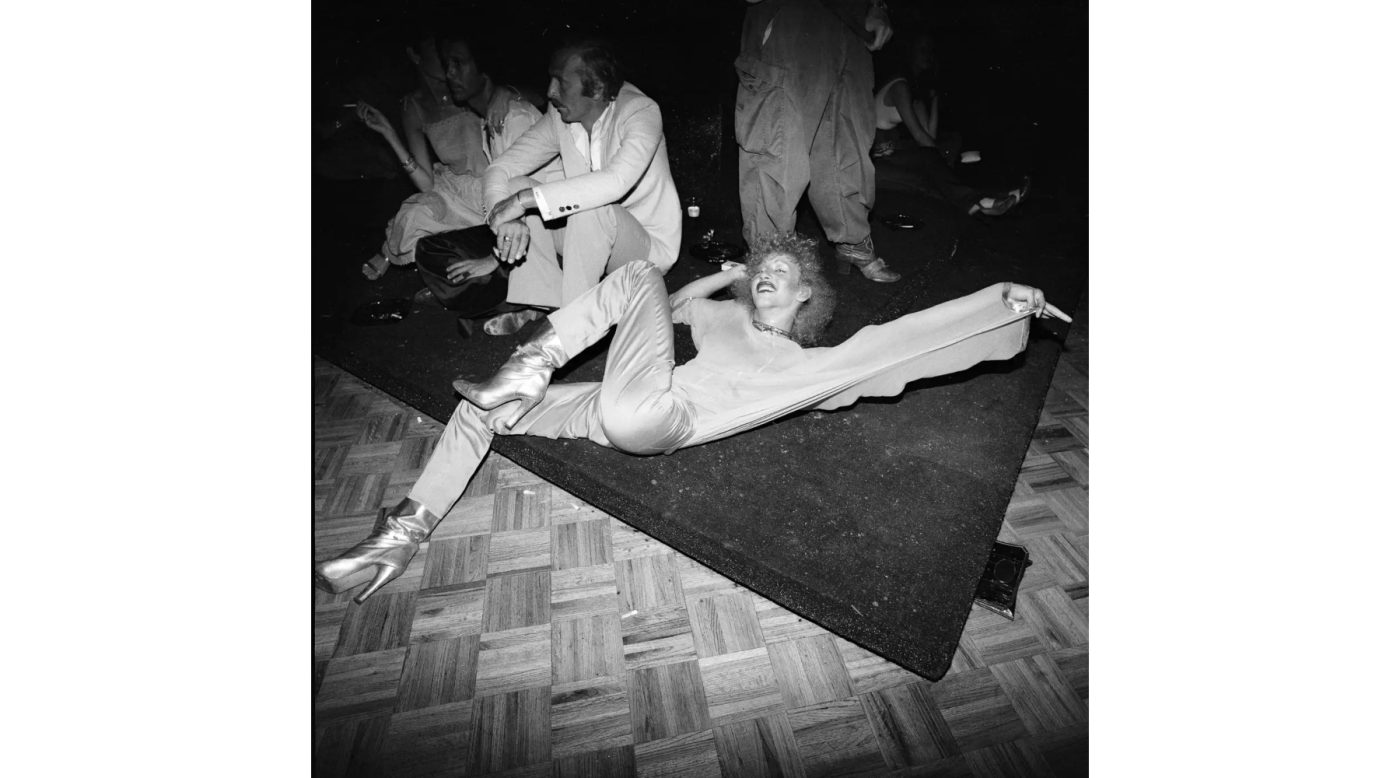

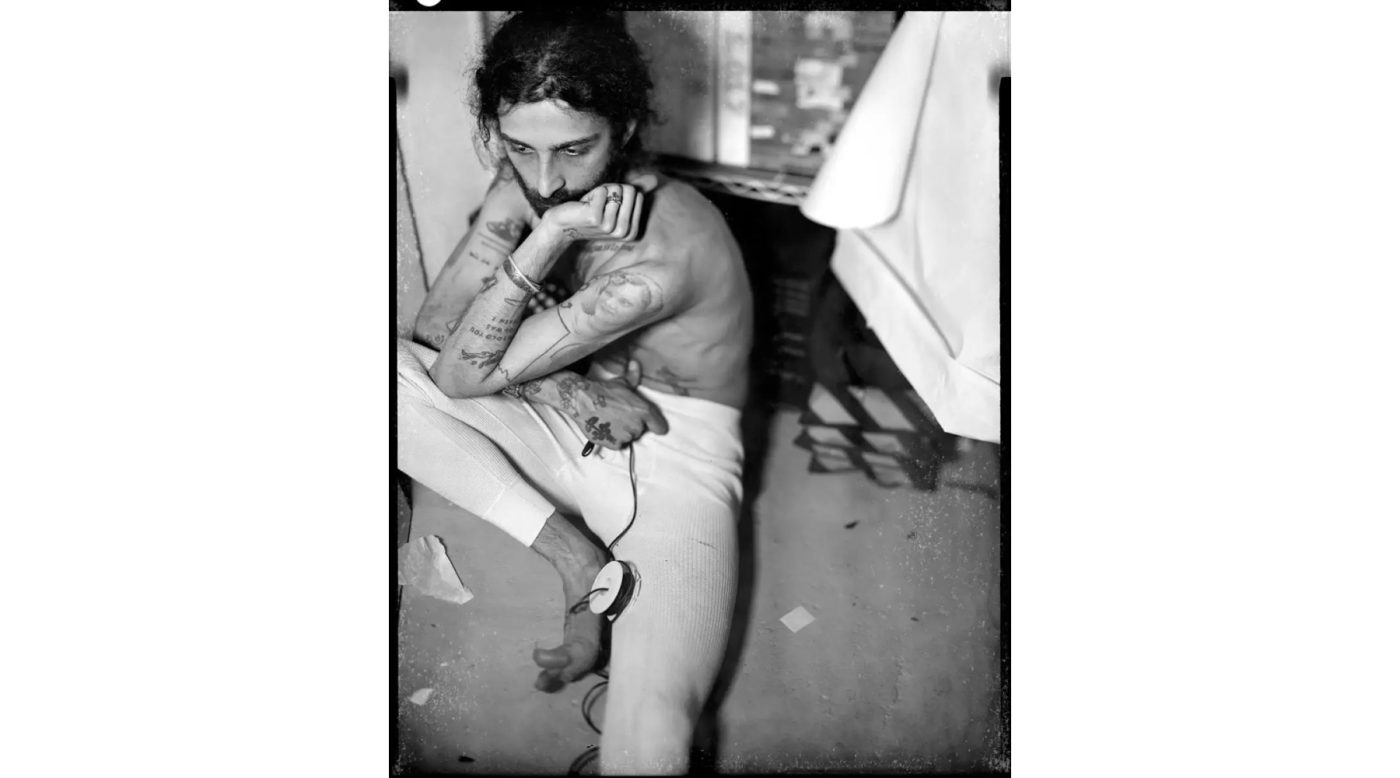

Among her adherents, “the most successful are ones who don’t try to replicate her style,” adds Humery, citing Nan Goldin. Goldin couldn’t be more different in some ways — particularly in that she knew her downtown New York subjects in the early work that made her famous — but she demonstrates a psychological acuity that echoes Arbus’s.

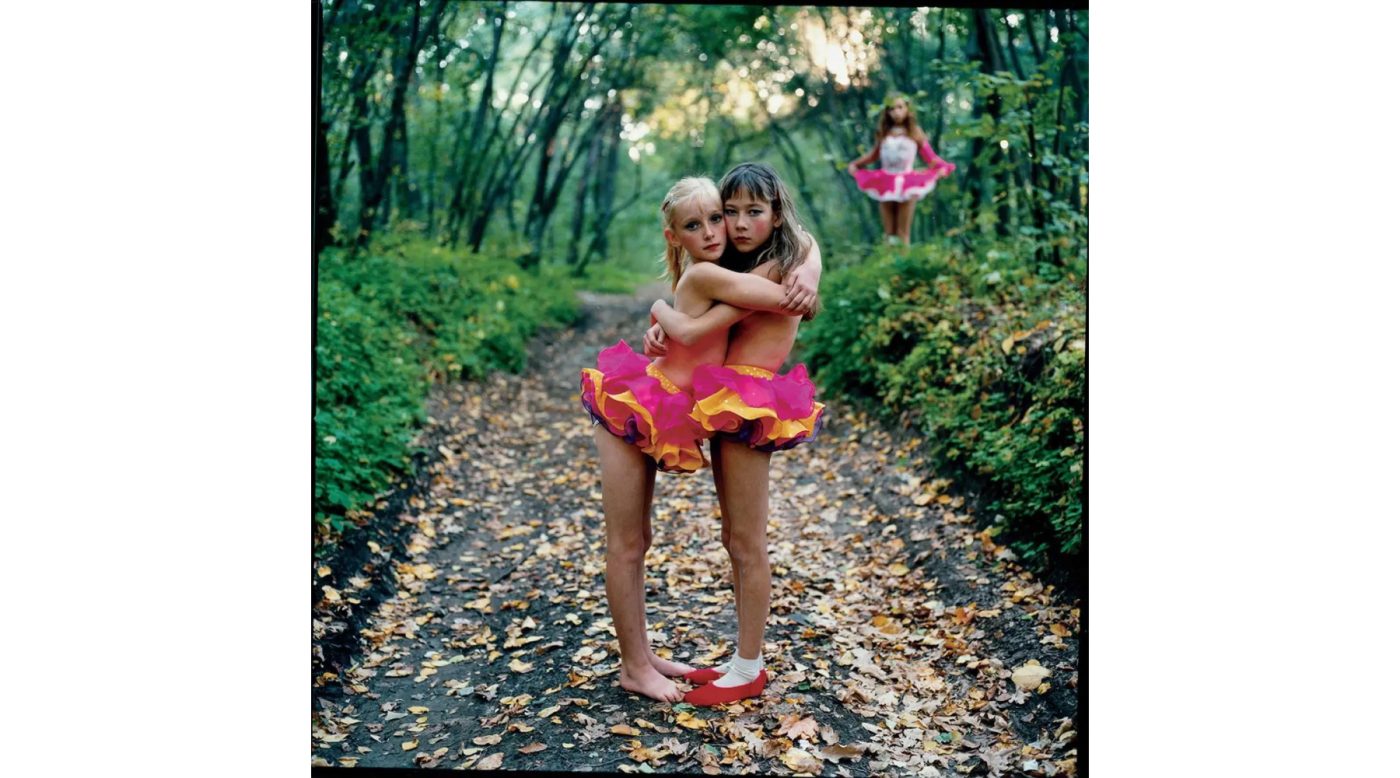

Among the talented photographers he represents or deals in, Clamp points to Meryl Meisler, Michal Chelbin, Ian Lewandowski and Rosalind Fox Solomon as bearing the Arbus stamp.

Anyone following in her footsteps surely has one big thing in common with Arbus, which perhaps gets lost in the complexity of her work and occasional controversy surrounding it: her absolute devotion to the medium of photography, so evident in “Constellation.”

“She was bonkers crazy about taking pictures,” says Selkirk. “She just loved it.”