November 27, 2017The skyscrapers are the sour cream of a skim milk society,” Donald Judd wrote in 1984. One of the most important artists of the 20th century, Judd was also an incisive philosopher-critic and found “plastic bureaucratic architecture” ripe for evisceration. In response, he built more than arguments — and now, Judd’s architectural works are the focus of a new exhibition in New York, “Obdurate Space,” the first dedicated to this part of his oeuvre.

Beyond the towering, tax-abating corporate palaces that only exaggerated the “snaggletoothed” Manhattan skyline (Judd was an advocate of symmetry), he railed against the ersatz historical jazz of postmodernism and the architecture-as-sculpture stance of so many museum commissions. Attuned to the built environment from a young age, Judd had watched art and architecture gradually grow apart and finally divorce, as the latter practice was reduced to “merely building.”

His brilliant scheme for reuniting the estranged couple was to make space his main concern, whether he was creating paintings, prints, sculptures, furniture or the buildings presented in the show, on view at the Center for Architecture through March 5. “Space is made by an artist or architect, it is not found or packaged,” Judd wrote in 1993, just months before his death at the age of 65. “It is made by thought.”

“Don’s practice was space,” says Flavin Judd, the artist’s son, who serves as copresident of the Judd Foundation with his sister, Rainer (both are from Judd’s marriage to dancer and choreographer Julie Finch). “Dealing with space, for him, meant dealing with any kind of space that he found interesting.” This made for a set of ideas and demands that were consistent across all of his projects. “The difference, of course, is that the problems you are solving in architecture are problems of use and utility as well as aesthetics. The problems that need solving in art are something else entirely.”

Judd purchased this five-story cast-iron building at 101 Spring Street in New York’s Soho in 1968 and subsequently renovated it, adorning it with minimalist works he and his friends created. According to the Judd Foundation, the building is where the artist “first developed the concept of permanent installation.” Photo by Joshua White, © Judd Foundation, licensed by ARS

Judd’s architectural projects began with the remodeling of his own loft on Manhattan’s 19th Street, followed by improvements to the five-story cast-iron building he purchased in 1968 at 101 Spring Street. “In New York, it was important to invent only additional architecture that would not harm the original architecture,” he wrote to artist Annabelle d’Huart. (The letter is among the musings collected in Donald Judd Writings, an idea-stuffed brick of a book published recently by the Judd Foundation and David Zwirner Books.)

The interior of 101 Spring was a Gesamtkunstwerk composed of carefully placed minimalist works made by Judd and his artist friends, as well as furniture and museum-quality decorative objects. Today, the painstakingly restored building is a sort of house museum on the upper floors, with a street-level gallery space that shows such artists as James Rosenquist, Richard Long and, currently, Yayoi Kusama.

When he moved to his property amid the desert landscapes of Marfa, Texas, where he eventually amassed some 20 structures as well as three nearby ranches — “Don couldn’t resist a good building,” Flavin notes — Judd further developed his architectural ideas.

Claude Armstrong and Donna Cohen, who organized “Obdurate Space,” first arrived in Marfa during the summer of 1982 and immediately began working with architect and artist Lauretta Vinciarelli to assist Judd. “Don was mysterious and intimidating looking, but actually quite pleasant and funny,” recalls Cohen, now coprincipal with Armstrong in their own eponymous architecture firm. “He trusted Lauretta to work with us on documenting various works of art, furniture and buildings.” Busy mornings spent in the studio, where Judd meticulously recorded the details of each project on yellow legal pads, often gave way to afternoon and evening explorations of West Texas.

“Judd approached architecture as a form of space making and construction that was related to, but also distinct from, his art,” says Cohen. “He gave himself rules for architecture that resulted in works that appear to be simple but are complex in the experience.”

The show presents five of Judd’s architectural projects, all produced during the last decade of his life: the concrete buildings in Marfa; the urban proposal for downtown Cleveland; the Eichholteren Haus, in Küssnacht-am-Rigi, Switzerland; the Kunsthaus Bregenz Office and Archive Building, in Bregenz, Austria; and Bahnhof Ost, in Basel, Switzerland. Newly created models, archival materials, photographs and digital renderings of works that were never realized make connections between the projects and the context in which they were conceived, revealing the breadth of scales and building types that interested Judd.

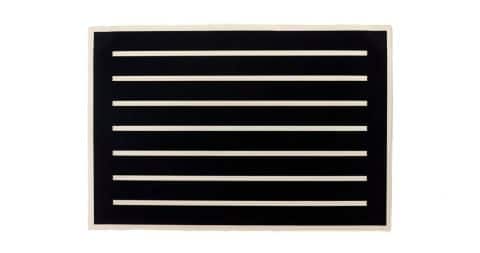

Judd’s Bahnhof Ost, a large office and university complex near the Basel train station, exemplifies many of the artist’s architectural principles. In 1992, after accepting an invitation to design its facade, he worked with the Swiss firm Zwimpfer Partner Architekten (now Ffbk Architekten) over a two-year period, up to the point when the building was permitted. Enclosed in absinthe-hued alluvial glass that takes on varying densities over the course of the day, the horizontally sited structure of steel and concrete is illuminated by skylights and a grid of windows. “His goal was to make a large-scale facility that was both coherent and diverse in its architectural spaces,” Cohen and Armstrong note in the exhibition wall text. They describe the resulting building (completed in 2000) as “a green mountain of atmospheric color effects reflecting, obscuring and revealing itself to the city.”

A rendering of an interior of one of Judd’s concrete buildings in Marfa, also featured in the Center for Architecture exhibit, illustrates the artist’s desire “to engage with space itself and not degrade it with extraneous cultural references or things that would make it more opaque,” as his son, Flavin Judd, puts it. Image by Paul Armstrong

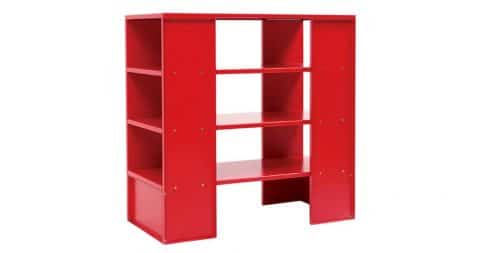

“For the projects that he designed from the ground up, it was about using the space in a way that made you aware of what it could do,” says Flavin. “He wanted to engage with space itself and not degrade it with extraneous cultural references or things that would make it more opaque.” The same impulse led Judd to create his own furniture.

An early experiment ended in disaster when he attempted to alter one of his own artworks (“essentially a rectangular volume with the upper surface recessed”) to create a coffee table. “This debased the work and produced a bad table, which I later threw away,” Judd recalled in his 1986 essay “On Furniture.” Lesson learned: “The configuration and the scale of art cannot be transposed into furniture or architecture,” he wrote. “The intent of art is different from that of the latter, which must be functional.”

Judd works in his Marfa print studio in 1982. Photo by Jamie Dearing, © Judd Foundation

After several years, he tried again, beginning with the walnut platform bed he slept on in Soho and pieces for Marfa, where the few nearby stores offered only what he called “fake antiques or tubular kitchen furniture with plastic surfaces printed with inane geometric patterns or flowers.”

“What’s beautiful about Judd is that he didn’t just complain — he made his own,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art director Michael Govan said earlier this year on the occasion of the museum’s acquisition (with the Huntington Library) of two prototype Judd chairs, which join the prototype desk already in the LACMA collection. Judd relied almost exclusively on others for fabrication, but he hammered these pine pieces together himself, giving young Flavin and Rainer a place to do their homework.

“Complaining only gets you so far,” according to Flavin. “If you’re serious about anything, you have to make an alternative.”