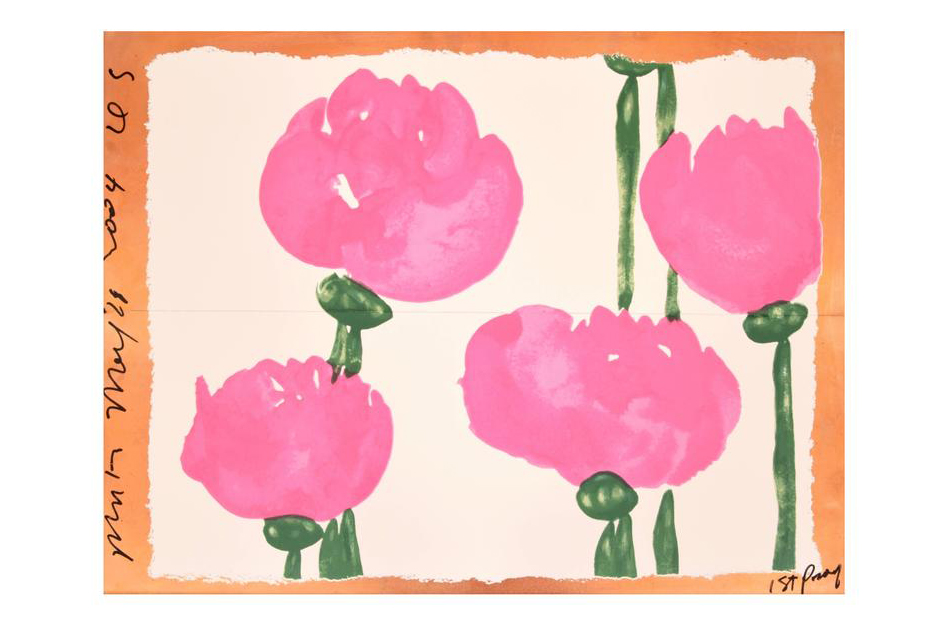

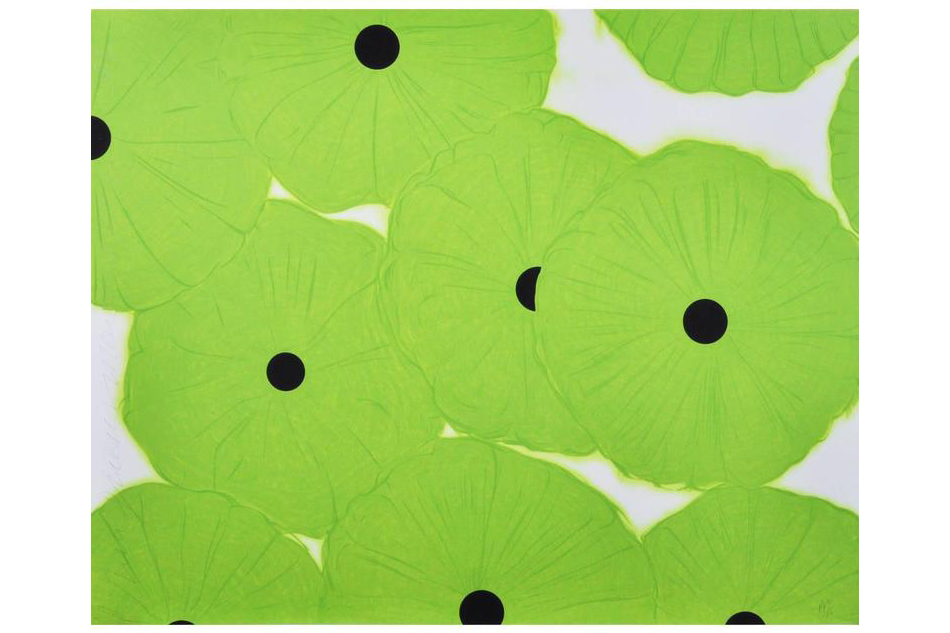

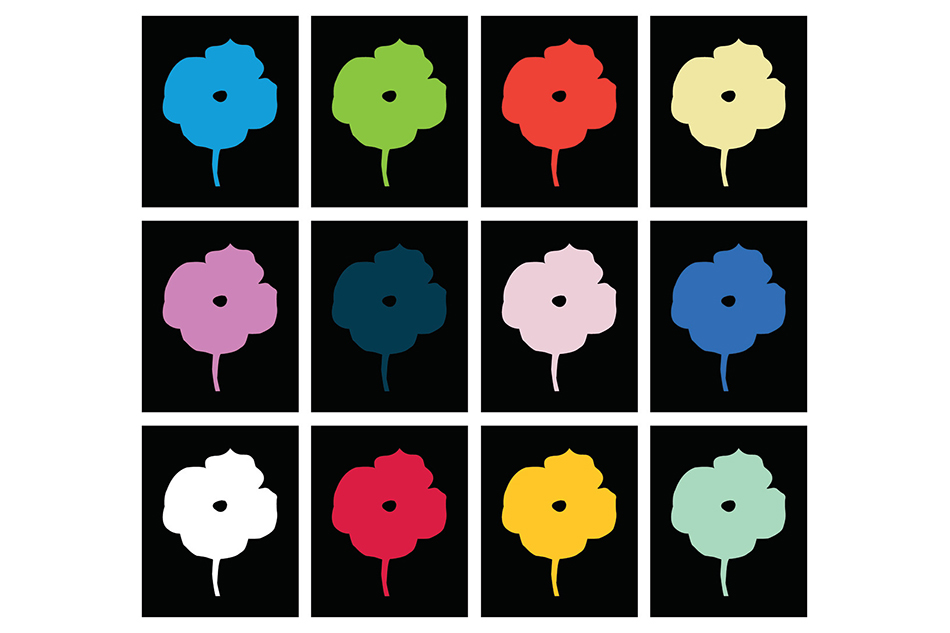

October 3, 2016Donald Sultan starts our conversation with a favorite aphorism: “The best art contains paradox, whether visual or narrative.” His signature paintings brilliantly illustrate this point: disarming fruits and flowers suspended incongruously in spaces that look clogged with smoggy soot. The artist came to acclaim in the 1970s with other neo-imagists like Ed Ruscha, James Rosenquist and David Hockney, artists who wrangled with content that yoked art to life.

In terms of paradoxes, Sultan presents his share. He’s been called a Pop artist but dislikes the label. In conversation, he sounds like a classical painter, comparing his charred colors to the bitumen effects in master canvases like those of Théodore Géricault.

He has built a career riffing on art history staples like the landscape and the still life, adding actual stuff — plaster, Masonite, tar — of what critic Irving Sandler called a distinctly vernacular view.

Donald Sultan’s Dramatically Dark Series

From 1984 to 1990, Sultan took what seemed like a thematic turn with “The Disaster Paintings,” depicting barely readable conflagrations, shadowy city crises and vagrant warehouses. In these works, the tension is between dark, barely choate scenes of urban trauma emerging from sonorous Turneresque atmospheres that seem otherworldly, even transcendent.

In “Donald Sultan: The Disaster Paintings,” at the University of Miami’s Lowe Art Museum, in 2016, the artist presented 11 of the most compelling eight-by-eight-foot works from the rarely seen series.

A Conversation with Donald Sultan

En route from his summer retreat on Long Island to his studio in New York City’s Tribeca neighborhood, Sultan shared thoughts on his career and the show.

Your flowers, tulips and dice have a presence that comes from combining size and the charmingly everyday. The force of the “Disaster” works is more theatrical.

Actually, I started in theater. I was part of the Tanglewood Youth Theatre [in Asheville, North Carolina]. I did serious summer stock and worked on set designs and scene painting. I got involved in radio and some independent movies as an undergrad.

How did fine art happen?

I thought traditional theater was dead — all art forms were closing that gap between the viewer and the work. And outside of serious conceptual bodywork by artists like Dennis Oppenheim, most fine-art performance was bad theater. I’d done the whole film thing, so I was not interested in video art. Also, actors, auteurs and filmmakers need layers of people to get ideas realized. An artist is actor, director and playwright in one. I like that control.

So you got a BFA in painting from the University of North Carolina in the early seventies, when the whole enterprise of painting was being questioned?

We’ve declared painting dead often, and how long has it showed us that it is never going away? We call classic films “old films,” we never call masterworks “old paintings.” Good painting is timeless.

You went on to get a master’s degree at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1975, when things like conceptual installation, assemblage and performance were the order of the day.

My generation was well past Ab Ex and Pop. We’d been taught to eliminate the gesture because it was too biographic, and we wanted to use form to make images that were experiential and real without necessarily using a brush.

The “Disaster” pieces are your most overtly painterly works, although you’re not applying pigments in traditional ways.

Pollock’s floor works influenced me — their immediacy and how they defied expected orientations. You look at them from any angle, and they made sense. I wanted to make images that read in any direction so that you had to confront shifting geometries and form as much as meaning. Maybe.

You use these gritty, construction-site materials. Were you influenced by the earth art of artists like Robert Smithson or Michael Heizer?

Maybe. I definitely liked Heizer’s land displacements. But an equally strong influence was my dad. He was a hobby artist, and he would share all that with me from early on. He inherited a successful business in auto parts and tire retreading but loved to paint, so all that was around me always.

“The images in the news fascinated me — charred buildings, smoke obscuring and changing forms, decay, the permanent becoming impermanent overnight.”

That partially explains the everyday media and subjects that often get you labeled a Pop artist.

Outside the smart work by Duchamp, I found most Pop appalling. When I make a totally common Sunkist lemon, it’s not about consumerism, it’s not an organic lemon — the lemon is there to add a formal compression, and that is what I am ultimately after.

Do you see the “Disaster” works as atypical?

Painting is painting, form is form. It’s been said that Carl Andre summarized the history of sculpture in an eighth of an inch. The spatial relationships and negative spaces I stress in all my work tie everything together. The geometry of a chair suddenly rotates in later work to become a smokestack. A smokestack in another work suggests to me the cylinder of a flower vase. The fire that spews out of a factory chimney makes me think of an energetic cluster of tulip stems. The main idea is reading changing shapes and geometries, not just objects or stories.

The “Disaster” series started in the eighties. Any personal or social significance to that onset?

The eighties were crazy. War between Iraq and Iran, cities burning. In the mid-1980s, Halloween was marked in Detroit by a kind of frenzy. Houses, commercial spaces, cars were burned. It became an odd yearly ritual. The images in the news fascinated me — charred buildings, smoke obscuring and changing forms, decay, the permanent becoming impermanent overnight.

Are you making a political statement about our troubled cities?

No. Manet’s historical The Execution of Emperor Maximilian [1867–69] depicts the world but focuses us on the abstract smoke from the guns to say what it wants to say. I work like that.

You stopped making these in the nineties. Why?

By the nineties, news coverage reminded us twenty-four/seven of these things in sensationalist ways. Recording in art didn’t seem needed.

They seem timely again.

I always wanted to show them. Support by the Lowe and the Modern in Fort Worth made it possible. The ephemeral style of these paintings says civilization is fragile. We think solid things like concrete cities — even empires — are permanent, but they’re transitory. This fragility of things repeats itself over and over. Suddenly, these paintings are relevant again, or maybe they never stopped being relevant.