February 9, 2025The name Yellow House Architects may bring to mind a leafy small-town cul-de-sac. But it turns out to be a fitting moniker for Elizabeth Graziolo’s award-winning New York City–based design firm.

In the five short years since Graziolo launched it, Yellow House — named for her favorite color — has become a glowing beacon in a vast field. For her clientele, her style, which she calls “clean classicism” — a design ethos rooted in classical principles of balance and proportion — offers the promise of inviting and harmonious spaces. For a younger generation of aspiring architects and designers, meanwhile, Graziolo is a symbol of hope and optimism, as the relatively rare female architect of color.

“Some kids see me and think, ‘Oh! There’s somebody who looks like me, I can do this! I can be an architect or an interior designer!” says Graziolo. “It really encourages kids of color to have role models and industry support.”

To that end, Graziolo gives her time and energy to a variety of organizations that help promote more diversity in her field. This year, she’s partnered with 1stDibs to curate the site’s Black History Month Collection, which supports Black sellers in the 1stDibs community. She’s also on the jury panel for a Female Design Council x 1stDibs grant to be awarded in March to an exemplary woman of color in interior design. Founded in 2016 as a professional support network for women in architecture, design and the applied arts, the Female Design Council is now a major advocacy organization helping build equity in a field long dominated by men.

“I’m looking for someone who is showing great creativity, someone who wants to push boundaries and who will eventually have an impact in the design industry,” Graziolo says of the potential grantees. “It’s a competition, and they will be head-to-head against amazingly talented designers. The question is, What do you do to set yourself apart?”

It’s a question that Graziolo knows well. “I won’t deny that I’ve had to work extra hard to prove myself, as a woman and as a Black woman,” she says. She recalls going to job sites where she’d walk into the room and be asked where the architect was. “Believe it or not, twenty years later, in some parts of the country, I still get that look,” she says. “You’re not taken seriously until you show that you know what you are doing.”

But Graziolo doesn’t linger on the adversity she’s faced. It almost came as a surprise to her, in fact. “I think it’s been a bit different for me since I didn’t grow up here,” she says.

Born in Haiti to a family of means, Graziolo was exposed to colonial European architecture and traveled in Europe as a child. At the age of 13 she moved to New York, where she excelled academically and graduated from high school early. By the age of 16, she was enrolled at the Cooper Union, the prestigious art, architecture and engineering school. She was so focused at the time, she didn’t really think about how homogenous the institution was. “I was really good at math and science, and I loved to draw, so I thought, I’m just going to go for this,” she recalls. She had considered pursuing structural engineering but ended up in architecture and loved the mix of math, creativity, rigor and conceptual thinking.

After graduation, she landed a job with architecture firm Cicognani Kalla, where she found an early mentor in cofounder Ann Kalla. She spent several years on staff there before she was hired by classically trained architect Peter Pennoyer, known for traditional design. At his firm, she ascended the ranks to partner, overseeing projects from grand historical estates to ground-up New York City luxury residences while honing her expertise in the ideals of classicism — balance, symmetry, proportion — and working with traditional materials, like plaster.

“Classicism is a language that has proved itself over and over again. Why not learn from it and use it, even in a contemporary way?” she says, noting her fondness for problem-solving when it comes to adapting historical spaces for modern use.

Classical principles inform her vision when engaging with modern spaces, as well. “I love good architecture. I love when things are well-thought-out. That’s why everything I do is about human proportion.”

Bringing a human touch to a practice that can be highly cerebral and alienating is one of Graziolo’s goals. She always starts with hand-drawn sketches, for instance. “There’s more of a human connection when something is made by hand,” she says. And she has a deep appreciation for artisans who are skilled with their hands, especially in crafts like plaster work and wood milling.

In drawing inspiration from the past, Graziolo also reaches far beyond Western design practices. “Traditions are different in Japan or Morocco, but they are still traditions,” she points out. “When I say clean classicism, that can apply to a riad in Morocco, too.

Since founding her own firm, Graziolo has been taking on more of an interior design role while continuing to practice architecture. “It all goes hand in hand,” she says. One of her earliest interior projects was the design of a model apartment for the Art Deco landmark One Wall Street, the first skyscraper to be converted from offices to luxury residences post-COVID.

“I love the Art Deco period, especially the blend of influences from ancient Egyptian art and architecture with the modern industrialization and glamour of the time,” she says. “This fusion resulted not only in a striking new architectural style but also in the creation of exquisitely luxurious furniture. I love almost anything by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann.”

In the One Wall Street model unit, she met the building’s opulent limestone facade with a creamy neutral palette (as well as some trademark dashes of yellow) and materials like shagreen and mohair, tying the space together with such statement-making designs as a vintage Vladimir Kagan Zoe sofa and Jean Royère–style sconces. “I love the use of some mid-century pieces,” she says.

Although Graziolo embraces history, her taste isn’t confined to a single style or era. She gravitates toward anything that is meticulously made and stands apart from the ordinary. “Good craftsmanship covers it all for me, from object design to architecture,” she says.

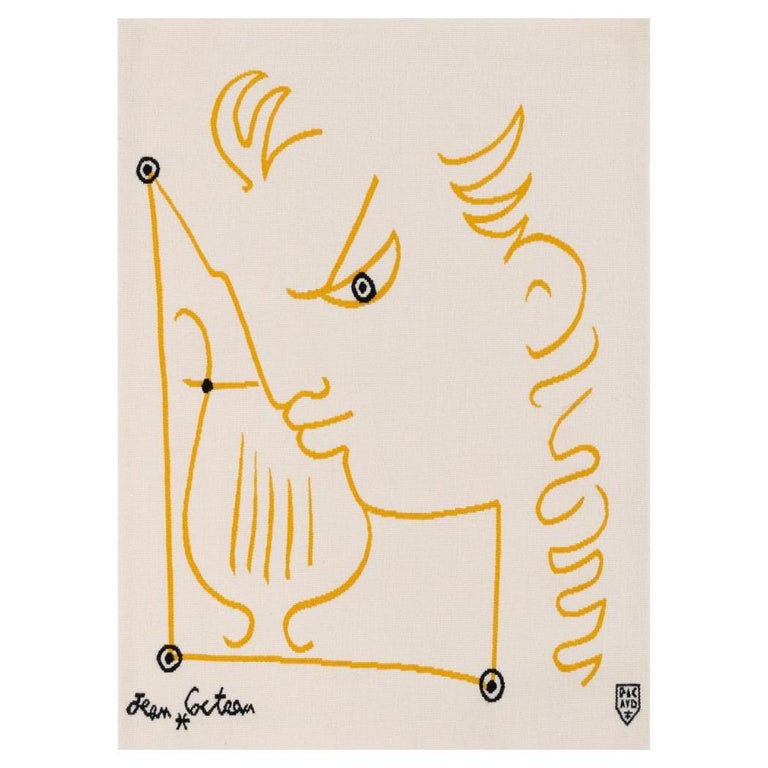

Her 1stDibs curation for Black History Month includes a variety of beautifully made, subtle statement pieces, like a large early-1930s Pierre D’Avesn for Daum glass vase with a relief of three swimming fish and a 17th-century French tapestry illustrating the History of Psyche. “I got hooked on tapestry two years ago,” she says. “People don’t use it that much anymore.” She points out that in the 17th century, tapestries were highly valued as both art and insulation for grand interiors. The one in her 1stDibs collection “is fascinating for its exquisite craftsmanship and storytelling,” she adds.

Graziolo is currently working on projects across the globe, from dwellings on Manhattan’s Upper East Side and in Upstate New York to far-flung residences in Turks and Caicos, Iowa and Miami. The Florida home “is super modern, which is something I have always wanted to explore,” she says. “People associate modernism with coldness or even brutalism. But we are going to make it feel warm and interesting.”

Graziolo has taken a similar approach in the design of Yellow House’s office, which accommodates a team of 18. “My goal was to make it homey, to design an inviting space where we wanted to come every day, and where clients felt at home, too,” she says. “It’s not like a traditional architectural office.”

She used soft leathers and woods in warm tones and carefully selected artwork to make it cozier, including a tapestry she found in a Paris flea market. It depicts a party scene, and she hopes it will inspire a collaborative atmosphere among her employees and clients. “I invite clients to participate as much as they can,” she says. “You’d be surprised. Sometimes they come up with ideas, and you’re like, Oh, my gosh, this is never going to work. And then it does!”

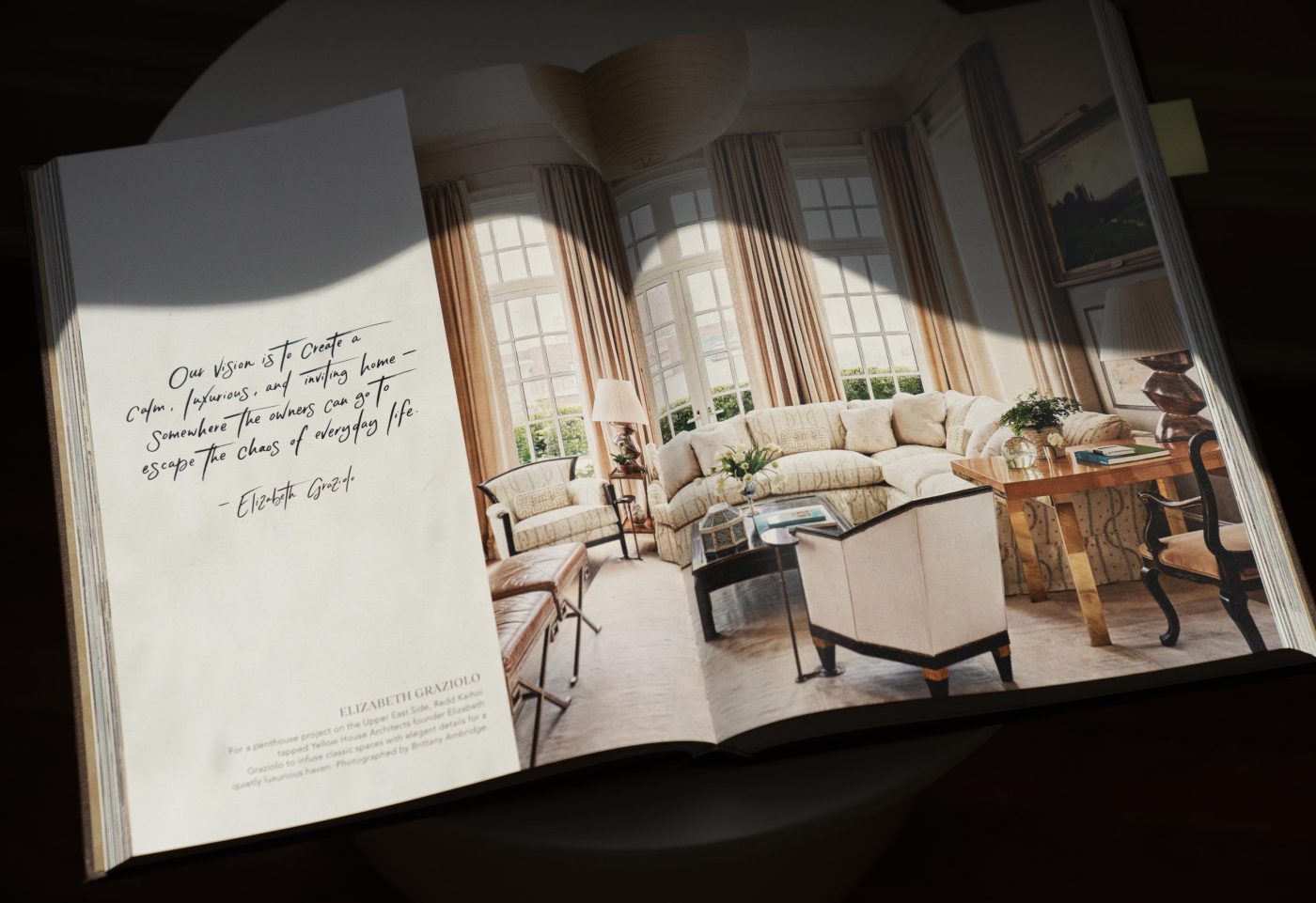

She cites a penthouse-apartment renovation in a historical building on the Upper East Side. “The client was very involved and focused and wanted to raise the roof to create more space. “I didn’t think we could, since the building was landmarked,” she recalls. “But we agreed to look into it, and guess what? We were very pleasantly surprised.” They were able to get two more feet of space.

“I learned that at times, it’s worth trying to push the buttons to see if we can change something.”